- Published on 13 March 2018

City in Motion looks at how spatial location helps create and maintain socio-spatial exclusion and marginality within cityspace, investigating the relationship between rental values and transport expenses in 6th of October City.

Introduction[1]

The backbone of every large metropolis is a well-functioning collective transit system. Buses, metros and tramways moving across networks of streets and roads, bridges and rail lines, are part of the bedrock upon which contemporary city life plays out. As such, mobility – the ability to freely and easily move from one place to another – is a fundamental component of the modern urban experience and a basic right that everyone should enjoy. Although it is possible to argue that Cairo’s transportation systems ‘do function,’[2] the city’s transport infrastructure nevertheless suffer from major problems.

The vast majority of the city’s population depends on some form of collective transport for their daily commutes. While only 10 percent of Greater Cairo’s[3] populace of over 23 million owns a private car, and just 8.7 percent of households, the mass transit needs of the city are vast.[4] Greater Cairo’s public transport authorities (Metro, tram and buses), carry a combined 1.4 billion riders every year.[5] This demand has been compounded by the emergence since the late 1970s of a host of new satellite cities around the edges of the metropolis whose residents are strongly connected to the city proper. As such, the need for means of collective transport has thus not only increased between existing and new urban settlements, but also within these new satellite cities. Whether one listens to ordinary city dwellers or studies government policy documents,[6] it is clear that the proportion between Greater Cairo’s collective transit capacity and the continuously growing urban public’s transportation demand is heavily skewed. However, not only does the capacity fail to meet demand on a city-wide scale, gross disparities also exist between neighborhoods within Cairo in terms of the delivery of transportation services and their accessibility.

With this in mind, this article explores the spatial distribution of urban transport services in one of Cairo’s satellite city suburbs and examines the degree to which these services are accessible to neighborhood residents. Representing one of the prime examples of the Egyptian government’s spatial development strategy, 6th of October City, located approximately 34km west of Cairo’s city center, provides a good case study for exploring how (neoliberal) central planning practices often contribute to patterns of urban service distribution that are socially unjust. Considered here are three geographical areas of 6th of October City that are seen to represent an urban center and periphery. In doing so, and following Dalia Wahdan’s earlier research,[7] the article investigates how spatial location helps create and maintain socio-spatial exclusion and marginality within cityspace. Two of the areas considered are privately-built residential neighborhoods located in 6th of October City’s central districts, while the third is a government-sponsored social housing estate that lies on the city’s spatial fringes. The article argues that the particular spatial configurations of 6th of October City, in itself a result of broader processes of neoliberal capitalist development, have given rise to socio-spatial disparities within cityspace. It demonstrates how the city’s transport network not only reflects but also actively reproduces social inequities between urban dwellers residing in different parts of the city.

Spatial Composition of 6th of October City

The Egyptian government notes that Egypt suffers from an uneven distribution of its population across its territory, where a majority of the population lives on a fraction of the land. This myth[8] was the basis for it in the mid-1970s to embark upon an ambitious spatial development strategy that aimed to redistribute the population more evenly across its vacant desert lands. What became known as the new towns project saw the establishment of a number of completely new cities on the edges of existing urban settlements. These ‘New Urban Communities’ aimed to create self-sustained growth poles in the desert that would absorb a growing population, while also redistributing economic activities.

Launched in 1981, 6th of October City was intended to be economically independent and geographically separate from existing urban agglomerations.[9] In the early 1990s, the original concept of the new towns and the associated land management policies underwent fundamental changes. Until then, the main demographic they had sought to attract had been the working classes through the building of large sections of state-subsidized affordable housing units. However, with president Hosni Mubarak’s push to accelerate the state’s neoliberal economic policies, which had begun under Sadat’s infitah (‘open door’) program two decades earlier, a more profit-driven ‘state capitalist’ approach to desert development was adopted.[10] For 6th of October City, this meant a dramatic expansion of its geographical boundaries into the surrounding desert and the sale of large tracts of land to private real-estate developers. The result was that private capital investments poured into the speculative housing market with units largely left vacant or stalled.[11]

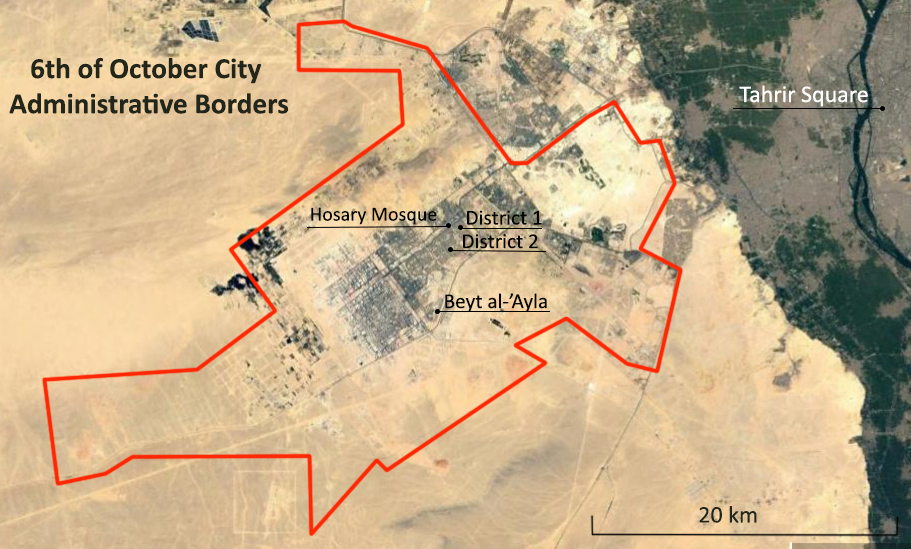

Figure 1. Satellite image of 6th of October City’s administrative borders (pre-2017) and the peripheral social housing project Beyt al-’Ayla. Source: Google Earth. Additions by Samir Shalabi, Nihal Ragab.

The city is currently made up of 12 formal residential districts distributed perpendicularly along a central axial road cutting through the entire city; one upscale district (al-hayy al-motamayyez); a tourist zone; as well as a large industrial zone in the far west. Two of the areas discussed here are formally known as District 1 and 2, while the third is a housing estate called Beyt al-‘Ayla and lies in the far southwestern periphery of District 6. Although the number of the city’s inhabitants barely reached 190,000,[12] the city’s boundaries encompass a colossal 681 square kilometres – almost as large as Cairo proper. Geographical distances within the city are consequently extremely large, making mobility and the availability of adequate networks of collective transportation pertinent issues to address.

Transport in the City Center

Until the mid-1970s, the Cairo Transport Authority accounted for the lion’s share of all collective vehicular trips within Greater Cairo. After that, private, informal microbuses started to appear and have since become the single most dominant means of above-ground collective transport in Cairo. Routes are carved out depending on market demand, meaning that areas with the highest population densities are more likely to be regularly served than where densities, and thus demand, are lower. Consequently, 6th of October City has suffered from an underdeveloped (informal) mass transit system. Although there has been talk of creating a publically-operated city-wide bus network, those plans have not come to fruition, leaving informal microbus, tuk-tuk (three-wheeled motorized rickshaw) and box al-Fayoum (quarter-truck) operators responsible for accommodating the city’s collective transport needs. According to one expert; “There were ideas for mass transit systems but […] the government would not provide it. It was always left for the private sector to initiate it so it is done with no regular disciplines or mechanisms; urban mass transportation is a real problem in the new towns,”.[13] Proponents of Egypt’s urban desert expansion say that although a functioning intra-city public transit system has not yet been developed, private suppliers do serve all areas of the city. However, a closer look reveals that a clear spatial polarization exists between 6th of October’s central districts and areas lying on the city’s fringes.

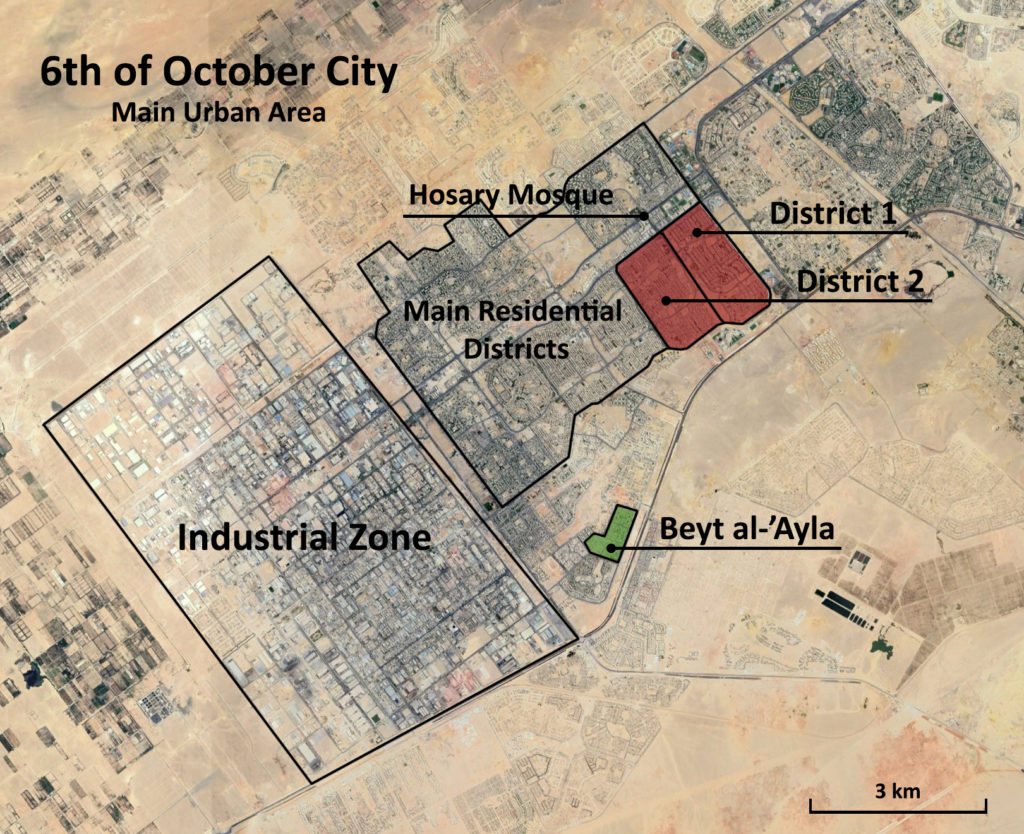

Figure 2. Satellite image of the main urban area of 6th of October City. Source: Google Earth. Additions by Samir Shalabi, Nihal Ragab.

The first and second districts are located just across the main axial road to Hosary Square, considered the heart of the city’s downtown. The distance from the beginning of both districts’ main commercial streets to Hosary Square is 500 meters, taking a little over five minutes to traverse. Adjacent to Hosary Square lies the Hosary mosque, in front of which has emerged an informal loading spot for microbuses. Here, vehicles from Tahrir Square, Lebanon Square and other central junctions of Cairo proper meet their end station and turn around to restart their routes. Many microbuses operating within 6th of October City also set out their routes from here to the rest of the city’s districts. They mainly go back and forth on the central thoroughfare, stopping wherever a passenger wants to hop off and at the roundabouts intersecting the main axis, which serve as central junctions for the city’s informal mass transit system.

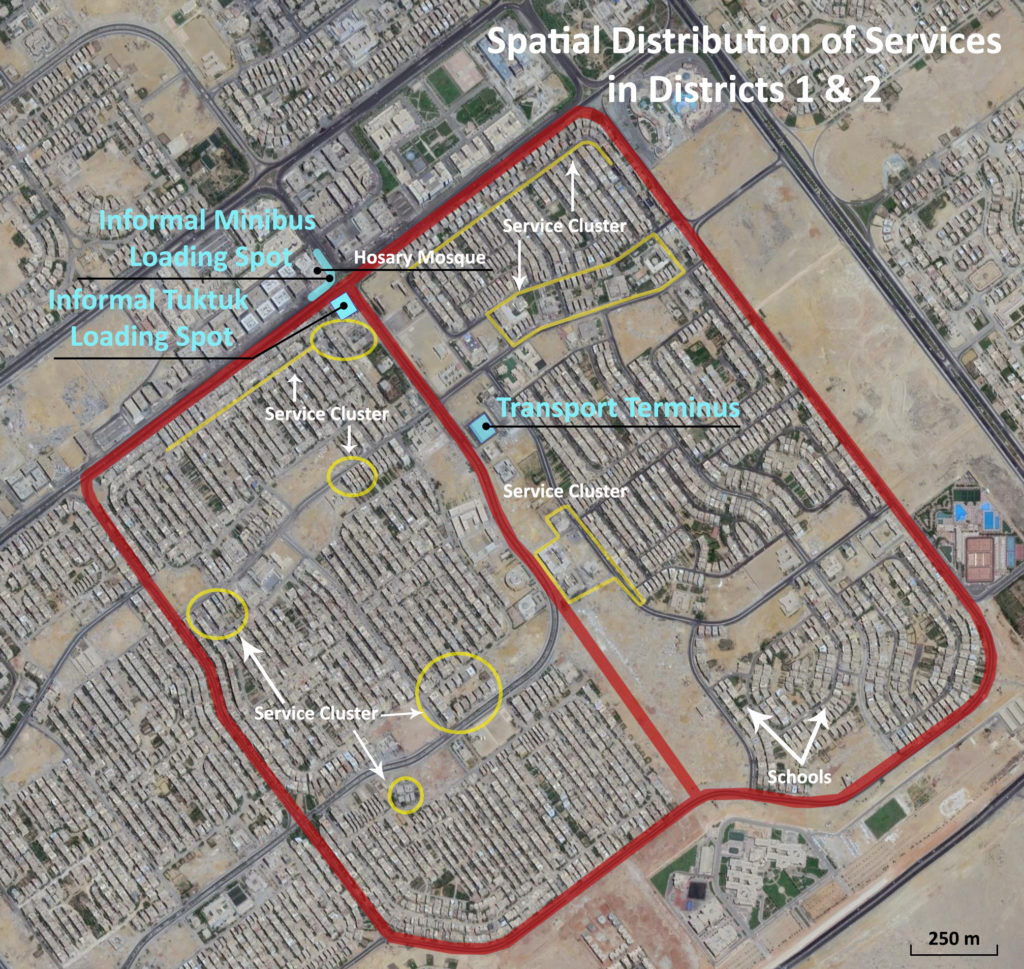

One of the exceptions are microbuses going to the sixth district where they depart from the axial road, entering the district and stopping at a large informal loading spot where mostly tuk-tuks and box al-Fayoums, but also a few microbuses, serve inner areas and the neighboring industrial zone. On the road between the first and second districts, approximately 600 meters and about a seven-minute walk from the Hosary mosque, lies a newly-built formal bus terminus for microbuses going back and forth between 6th of October and Cairo proper and other governorates. Previously, an informal loading spot was located about 200 meters closer to the Hosary mosque but was abandoned for the new terminus. Also, on the corner between the first and second districts lies an informal loading spot for tuk-tuks, the main means of motorized vehicular travel within the city’s districts.

The first and second districts are thus at least nominally connected to three collective transit nodes (Hosary mosque loading spot, bus terminus, corner tuk-tuk loading spot) located relatively close to the residential areas. Although inner areas of the districts are to a lesser extent served by microbuses, tuk-tuks are readily available. Also, and as will be shown, since these districts are comparatively well off economically, transport costs do not represent a significant burden on household finances. Based on field work, households in the first and second districts spend only 6.5 percent of their monthly income on transport, but an incredible 65 percent on rent (Table 1). This can be compared with the average expenditure on transport and rent in Giza writ large, both of which have been calculated to be around 7.4 and 24 percent of monthly income respectively (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of average monthly income and expenditure between study areas

| Districts 1 & 2* | Beyt al-’Ayla* | Giza | ||

| Total HH income | EGP | 4600 | 1500 | 2686** |

| Rent expenditure | EGP | 3000 | 700 | 650** |

| % of income | 65% | 46.7% | 24.2%** | |

| Transport expenditure | EGP | 300 | 450 | 199 |

| % of income | 6.5% | 30% | 7.4%*** | |

| Sources:

*Based on neighborhood residents and a Facebook group advertising rental apartments in 6th October. **10 Tooba. BEDI – Affordability. September 2016 ***Expenditure percentages for urban Egypt based on CAPMAS 2015 HIECS. |

||||

The lower than average transport-to-income ratio can be attributed to the fact that these areas are located in geographically central locations, proximate to workplaces and service clusters, allowing for short trips. In accordance with mainstream theories of urban structure and rent determination, the basic model of which holds that ‘central locations in cities require low transport expenditures and command high rents, while peripheral sites have low rents but involve high transport expenditures,’ an inverse relationship between rent levels and transport expenditures can be identified in the first and second districts.[14]

Figure 3. Spatial distribution of services in districts 1, 2. Source: Google Earth. Additions by Samir Shalabi, Nihal Ragab.

In interviews with neighborhood residents, they did not consider the distance to Hosary Square, around which lies a lively commercial area, or to other service clusters within the districts, to constitute a problem in their daily lives. In fact, the physical lack of any service was never mentioned by residents.

Transport on the Spatial Fringes

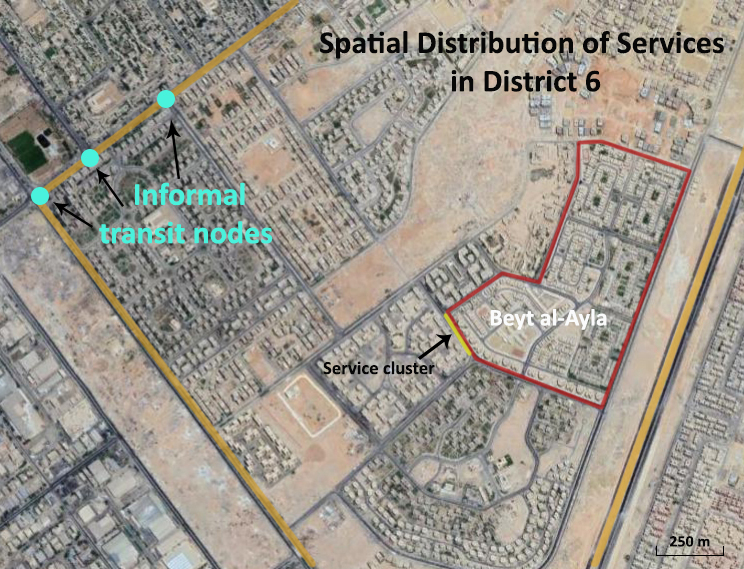

To adequately assess the distribution and accessibility of transport services within the city, a neighborhood located far away from the central districts is used here to represent its spatial periphery. Beyt al-‘Ayla,[15] whose population is now largely dominated by Syrian refugees, lies in the poor sixth district on the southern fringes of the city. Residents in Beyt al-‘Ayla typically have lower working class jobs, most being unskilled workers. With the Hosary mosque located approximately 10 kilometers to the northeast along the road network, the area is geographically distant from the city’s central areas. The main means of transport available to inhabitants of Beyt al-‘Ayla is the tuk-tuk, while the occasional microbus traverses its border.

Despite a small cluster of very basic service outlets across the southwestern border of Beyt al-’Ayla, the nearest well-sorted commercial cluster is at Emtedad al-Central Road about three kilometers away, which residents can reach by tuk-tuk paying around LE10 for a round-trip. If they need to travel to Hosary Square, they need first to take a tuk-tuk to the nearest transport node at Emtedad al-Central Road and change to a microbus, the fee of which is about LE3, making it an LE16 round-trip, or more. People who need to travel to areas in Cairo proper such as Ramsis or Tahrir Square need to pay an additional LE4-5 (LE9-10 for round-trips).

Figure 4. Figure 39: Distribution of service outlets around Beyt al-‘Ayla. Source: Google Earth. Additions by Samir Shalabi, Nihal Ragab.

During interviews, residents regularly brought up the problem that the cost of travel represents in their lives. While rents in Beyt al-‘Ayla are less than a third of those in the more central districts, spending on transport was five times higher in relation to income, eating up 30 percent of it, or four times the urban average (Table 1), as lower income households live in this spatially marginalized neighborhood.

Socio-Spatial Polarization of Transport

There clearly exists a territorial discrepancy in terms of the delivery and accessibility of transportation services within 6th of October City. This socio-spatial polarization can, on a broader level, be seen through the process of uneven (spatial) development;[16] the solutions to capitalism’s recurring tendency towards overaccumulation manifested geographically in how regions deemed economically profitable are able to attract capital investments while others are not.[17] The result is an unequal distribution of resources across space.[18] In the context of Sadat’s infitah policies, what David Harvey has called ‘spatial fixes’ would be implemented in response to problems of overaccumulation.[19] To solve the overaccumulation crisis, the government strove to develop industrial enterprises, accompanied by large tax and investment incentives to attract private business.[20] From the initial idea of the new cities, and particularly 6th of October, being to deliver an equitable distribution of resources to their inhabitants and provide for low-income people, the government, and specifically the 6th of October city authority, began privileging the interests of the business sector at the expense of the city inhabitants.[21]

The socio-spatial expression of this process was that areas in central 6th of October maintained a high level of economic development while remoter ones, such as Beyt al-‘Ayla, were left acutely underserved. Although formal public transport services are non-existent throughout the city, other services, such as markets, health clinics, schools and restaurants are concentrated in the downtown districts, which also have prompted the development of informal transport networks there. This political economy of space and marginality has been generated, in part, by the government’s elitist urban policies, but more prominently through the deregulation of Egypt’s market for social services. As has been the case with downtown Cairo,[22] letting market forces dictate the provision of social goods, such as education, health, housing and transport, has led to a subtle process of gentrification of the city’s desert suburbs. While both peripheral and central areas depend on services, only the latter have managed to attract capital investments, as it is there profitability is highest.

Egypt’s Urban Transport Policy: Too Little, Too Late

In light of the above, it is worth addressing the urban transport policies Egypt is pursuing. In 2015, the Egyptian government expressed its ‘full commitment’ to achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2015-2030 (SDG).[23] Goal number 11 of the SDG stipulates that countries aligned with the SDG agenda should by 2030 ‘provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons.’[24]

Pursuant of the UN 2030 agenda, Egypt launched its so-called Sustainable Development Strategy: Vision 2030 (SDS), encompassing economic, social and environmental dimensions of development. Each dimension includes several ‘pillars’, one of which is urban development.[25] The pillar declares that the government aims to no less than double the public transportation ridership by 2030 through increasing the capacity and quality of existing transit systems.[26] The SDS and SDG goals are extremely ambitious and should indeed be pursued. However, there are sadly no indications that current Egyptian urban policy will allow for these goals to be met. Of LE26 billion planned to be allocated to the transport sector in the state’s national FY 2016/2017 budget, only 5.5 billion, or 21 percent, went to public transport.[27] Although this represents a LE1.5 billion increase from the FY2015/2016 budget, it still is a very low number relative to demand.[28]

Moreover, although the construction of the metro’s fourth line will soon begin and a small fleet of ‘smart buses’ was recently launched,[29] for a megacity such as Cairo, the supply of mass transit is extremely insufficient, particularly compared to comparable cities around the world.[30]

With traffic congestion – an urgent problem with adverse economic and health effects[31] – not being taken seriously, and public transportation not being adequately developed, there is simply no way Egypt can meet the urban development goals it has proposed. Instead of prioritizing the construction of new highways and developing roads in Cairo’s outlying upscale areas which only tender to the needs of the moneyed classes, and building new desert towns from scratch, the prime example of which is the New Administrative Capital, the government should focus its efforts on upgrading the country’s public transport infrastructure, which millions of Egyptians use on a daily basis. Unfortunately, the prognosis for the future is bleak, partly due to the rising private car ownership and partly because of the government’s passive urban transport policy. The most likely future scenario is that the country’s transportation and traffic problems will remain unaddressed until the situation reaches a point of total crisis. What we need is a total overhaul of the way Egypt manages its cities and genuine structures of democratic local governance.[32] Only then, the authorities may start granting these issues the attention they deserve.

Acknowledgements

Wrtten by: Samir Shalbi

Editor: Yahia Shawkat

Main Image: Transport in Beit al-‘Ayla, 6th of October City. Photographer: Samir Shalabi

Notes & References

[1] This research is partly based on six months of fieldwork conducted as part of my MA thesis entitled ‘City Margins and Exclusionary Space in Contemporary Egypt: An Urban Ethnography of a Syrian Refugee Community in a Remote Low-Income Cairo Neighborhood,’ which can be accessed here. Sources used for the present paper include about 30 interviews with residents of central and peripheral areas of 6th of October City, two interviews with Cairo-based urban planning specialists, ethnographic observation and satellite imagery.

[2] Sims, D. (2012) Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City out of Control. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. p. 228.

[3] Greater Cairo consists of the governorates of Cairo, Giza and Qalioubiya.

[4] Authors’ calculations based on the 2017 census by CAPMAS (total number of licensed private cars in Cairo, Giza, Qalioubiya governorates (2,403,750) divided by total population of Cairo, Giza, Qalioubiya governorates (23,799,114) x 100).

[5]CAPMAS. Inner and Intra-city Public Transport Statistics 2015/2016. P52 (Arabic)

[6] Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt’s Vision 2030. Official report.

[7] Wahdan, D. (2012) “Transport thugs: spatial marginalization in a Cairo suburb”. Bush, R., Ayeb, H. (eds.) Marginality and Exclusion in Egypt. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. p. 112.

[8] For more on this, see Shawkat, Y. & M. Hendawy (2016) “Myths and Facts of Urban Planning in Egypt”, The Built Environment Observatory http://marsadomran.info/en/policy_analysis/2016/11/501/

[9] World Bank. (2008) “Arab Republic of Egypt: Urban Sector Update.” p. 55-6.

[10] World Bank. (2008“Arab Republic of Egypt: Urban Sector Update.”. p. 56.

[11] Sims, D. (2014) Egypt’s Desert Dreams: Development or Disaster? Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. pp. 128, 150.

[12] CAPMAS. 2016 Population Estimates by Markaz and Shiakha. Qism 1,2, and 3, 6th October, Giza.

[13] Ahmed Yousry. Professor of Urban and Regional Planning at Cairo University. Personal interview. April 2017. Cairo.

[14] H.W. Richardson, (2013) The New Urban Economics: And Alternatives. Routledge. p. 86.

[15] Beyt al-‘Ayla, part of Hosni Mubarak’s National Housing Project, was originally intended for lower-middle income Egyptian nuclear families. The area encompasses roughly half a square kilometer and was planned to provide to its inhabitants ‘all the basic services for citizens, whether it be schools, markets, playgrounds or green spaces.’ Thabit, H. (2007-09-24) “Gawla gadida li-Mubarak fi itar al-mashro’ al-qawmi li-l-Iskān” Egypt News https://www.masress.com/egynews/24835

[16] Smith, N. (1990) Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space (3rd ed.) Athens/London: The University of Georgia Press. p. 197, 203.

[17] Harvey, D. (2003). The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 115-116.

[18] Smith, N. (2008) Uneven Development. p. 4.

[19] Harvey, D. (2003). The New Imperialism. pp. 115-116.

[20] Wahdan, D. (2001) Building 6 October City: Local Politics and the Social Production of Uneven Spatial Development. Unpublished MA thesis. Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Psychology, American University in Cairo. pp. 70-72.

[21] Hobson, J. (1999) “New Towns, The Modernist Planning Project And Social Justice: The Cases Of Milton Keynes, UK And 6th October, Egypt”. Working Paper No. 108, Development Planning Unit, University College London; Ahmed Yousry, Professor of Urban & Regional Planning, Cairo University. Personal interview.

[22] Khalil, O. (2016-03-03) ”Fada’at al-Qahira bayn al-irtiqa’ wa al-‘askara,” (Spaces of Cairo Between Upgrading/Gentrification and Militarization) al-Safir. http://arabi.assafir.com/article/4326

[23] Voluntary National Review 2016: Egypt. UN Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/memberstates/egypt; UN Sustainable Development Goals 2015-2030. http://www.arabstates.undp.org/content/rbas/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html

[24] ‘Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable,’ UN Sustainable Development Goals. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/

[25] Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt’s Vision 2030. Official report. http://www.mfa.gov.eg/SiteCollectionDocuments/SDS2030_English.pdf

[26] Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt’s Vision 2030. Official report. pp. 259, 273.

[27] Shawkat, Y. The Built Environment Budget 2016/2017: Part II: Spatial Justice by Sector, Transport. http://marsadomran.info/en/policy_analysis/2017/06/854/

[28] The Built Environment Budget 2015/2016: Transport. http://marsadomran.info/en/policy_analysis/2016/11/672/

[29] “Construction of metro’s fourth line infrastructure to begin in December”. Al-Masry Al-Youm. (December 3, 2017). http://www.egyptindependent.com/construction-of-metros-fourth-line-infrastructure-to-begin-in-december/; “A New Batch of ’Smart Buses’ to Operate in Cairo by Next Month”. Egyptian Streets. (October 25, 2017). https://egyptianstreets.com/2017/10/25/a-new-batch-of-smart-buses-to-operate-in-cairo-by-next-month/

[30] World Bank Traffic Congestion Study: Executive Note (2014). p. 5. http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/TWB-Executive-Note-Eng.pdf

[31] World Bank Traffic Congestion Study (2014); ” Road Accidents Cost Egypt LE 30.5 Billion in 2015: CAPMAS”. (August 22, 2016). https://egyptianstreets.com/2016/08/22/road-accidents-cost-egypt-LE-30-5-billion-in-2015-capmas/

[32] The role of elected officials in local government (Local Popular Council, or LPC) is largely consultative, while since 2011, they have been dissolved and yet to be re-elected (See: Khazbak, R. “In Egypt, there is no local government”, Mada Masr 28.03.2016 https://www.madamasr.com/en/2016/03/28/opinion/u/in-egypt-there-is-no-local-government/). In addition, Local Administration Law 43/1979 does not apply to New Cities such as October 6th, which operate under the exceptional jurisdiction of New Urban Communities Law 59/1979, without any elected representation (For more see: Tadamun. “Egypt’s New Cities: Neither Just nor Efficient”, Tadamun 31.12.2015 http://www.tadamun.co/2015/12/31/egypts-new-cities-neither-just-efficient/?lang=en#ref13