- Published on 04 November 2019

As part of the Built Environment Observatory’s series on the new Construction Violations Reconciliation Law, a law that is believed to have a massive effect on housing and cities in Egypt, we analyse the size of the informal private sector, which is the target of the new law.

Click here to read the latest article 2021

Introduction

Egypt builds around one million units a year, a large number when taking into account population increase. Since the 1950s, three main sectors have provided this housing. The informal private sector, which builds without permits on mostly private agricultural land, the formal private sector, which builds on government-sanctioned subdivisions, and the public sector through an array of state-owned agencies and enterprises.

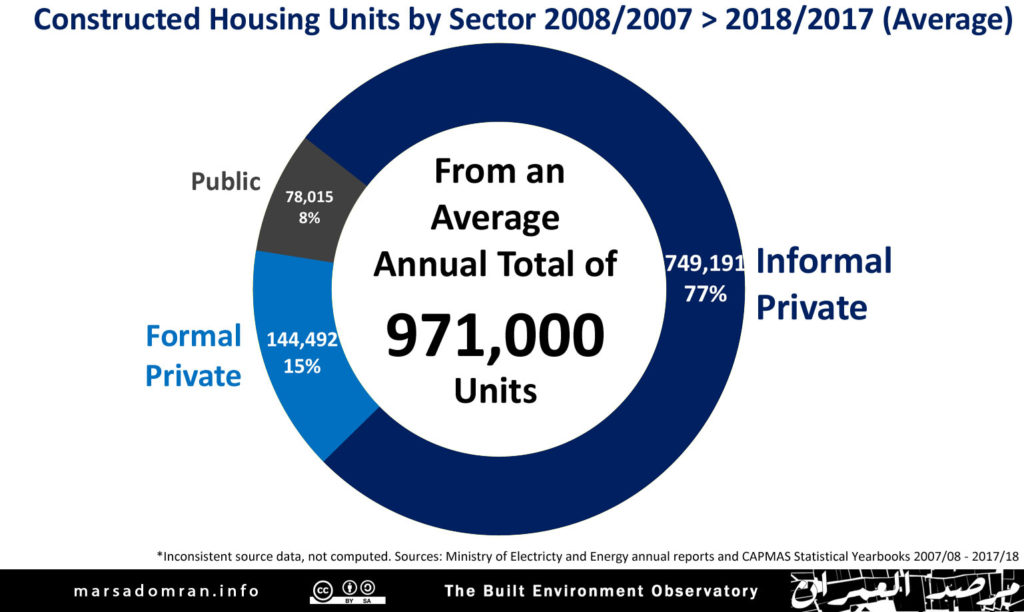

Leading these three sectors by a large margin, is the informal private sector, which includes a vast range of builders, from individuals building owner occupied homes, to investors building condos, from humble shack communities, to expensive golf resorts. Over the last decade, housing that is seen as informal by the government has contributed the vast majority of all housing built: 77% (Figure 1). Trailing it by some distance was the formal private sector at only 15% of housing, including individuals through to large property developers. At 8% comes the public sector in third place, building subsidized social housing, as well as thousands of for-profit housing units.

Figure 1

How can we Measure Informal Production?

Housing statistics for the formal private sector and the public sector are collected on an annual basis by the government,[1] however no information is collected on informal housing. The Ministry of Housing’s Organisation of Technical Oversight on Buildings (OTOB), has stated that there are almost three million informal buildings in Egypt constructed since the year 2000.[2] But this does not tell us how many units are in them, which could be millions as each building would have between three to four units, while it is not disaggregated by year. The information is also based on police reports of building violations, which may include more than one violation per building, or ones that have been corrected or demolished, and therefore not informal anymore.

But there is other official information that can be used to enumerate informal housing based on the methodology developed for our Build Environment Deprivation Index’s Secure Tenure indicator. Every year, the Ministry of Electricity and Renewable Energy releases its annual report which states the number of residential subscribers.[3] By deducting the annual increase in subscribers, we are able to infer the net annual additions of new homes. Subtracting the formally enumerated housing units from this total, then gives us a figure for informally built units.

Construction by Sector 2008 > 2018

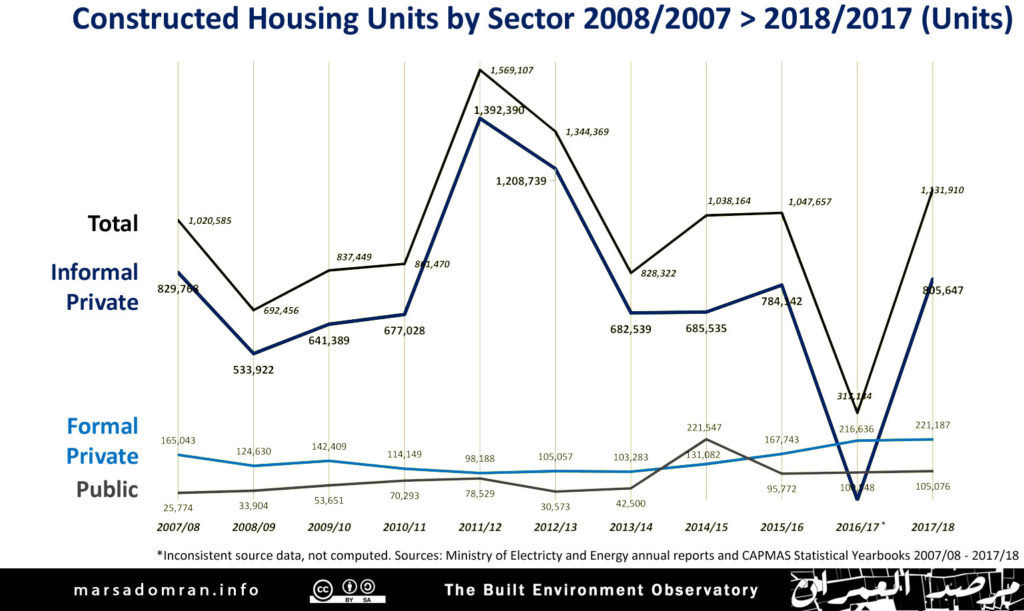

In the eleven years between 2007/2008 and 2017/2018, where data was available, 10.7 million units were built, of which 8.2 million were through the informal private sector alone (Figure 2).[4] In contrast, the formal private sector built 1.5 million units in the same time frame, while the public sector built 858,000 units.

Figure 2

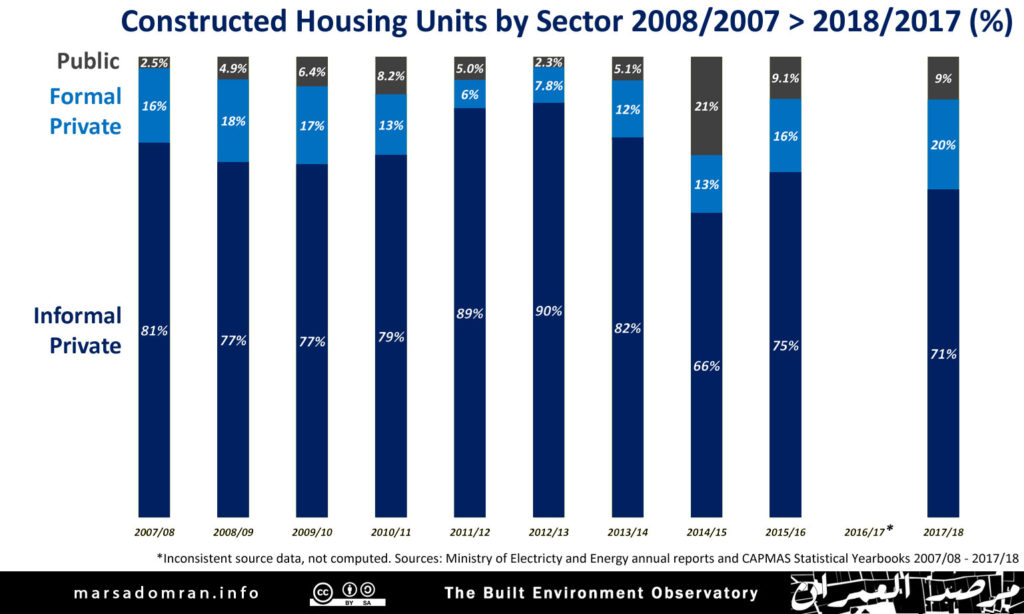

Focusing on the weights of each sector, we find the informal private sector consistently dominating housing production over the eleven-year period, with a low of two thirds in 2014/2015, and a high of 90% in 2012/2013 (Figure 3). On the other hand, the formal private sector has fluctuated between a low of 6% to a high of 20% over the same period with an average of 15%. The public sector averaged almost half of that at 8%, fluctuating between a low of 2.3% and a high of 21 percent.

Figure 3

Is the 2011 Revolution to Blame for Informal Production?

Housing production that is considered informal by the government goes back sixty years, is nothing new. Zooming in on the last decade through the graphs shows that in the three years leading up to the uprising, 2007/2008 through 2009/2010, the informal private sector built two million units (Figure 2), comprising 67% of total production (Figure 3).[5] A significant majority. Over the three years after the uprising, 2010/2012 through 2013/2014, 3.2 million units were built by the informal private sector (Figure 2), comprising 81% of all units built (Figure 3). This represents a 30% increase over an already high output, though both the formal private sector and the public sector show production shrink by about 22% over the same period, giving more share to the informal sector. Another reason behind the post revolution spike, especially in 2011/2012, is the increase in extending formal electricity to informal units, and not necessarily in construction, as owners could have built them many years prior and their applications were simply not accepted.[6]

What are the Reasons Behind Informal Production?

There is a long list of factors that would make the government label certain buildings as informal. What follows is short summary of the more relevant of them to the Reconciliation Law.

Official Marginalisation of Self-build

Despite Egyptian preference of self-build, also known as the social production of habitat, where in 2017 65% of people in Egypt were living in a self-built home,[7] the government does not support it. The supply of formally subdivided land by the government (mostly in the New Cities), is far behind the rate of construction on private agricultural land.[8] While most of this land is sold to large scale developers building unaffordable gated-compounds, and the small portion sold as ‘social housing’ plots, is too expensive for the low income families to buy.[9]

Unrealistic Building Laws

While hundreds of legislative acts have been passed over the last half century to shape the built environment, stipulating steep fines and jail terms for those who do not comply, the state has also suspended these laws through a host of ‘temporary’ reconciliation laws to legalise thousands of buildings that did not comply with the law.[10] Even those who wished to comply with the law, were thwarted by the bureaucratic complexities that held vague outcomes for what they intended to build.[11] These have all meant that the rule of law is not respected, and generally has eroded.

Corruption in Public Land Allocation/Use

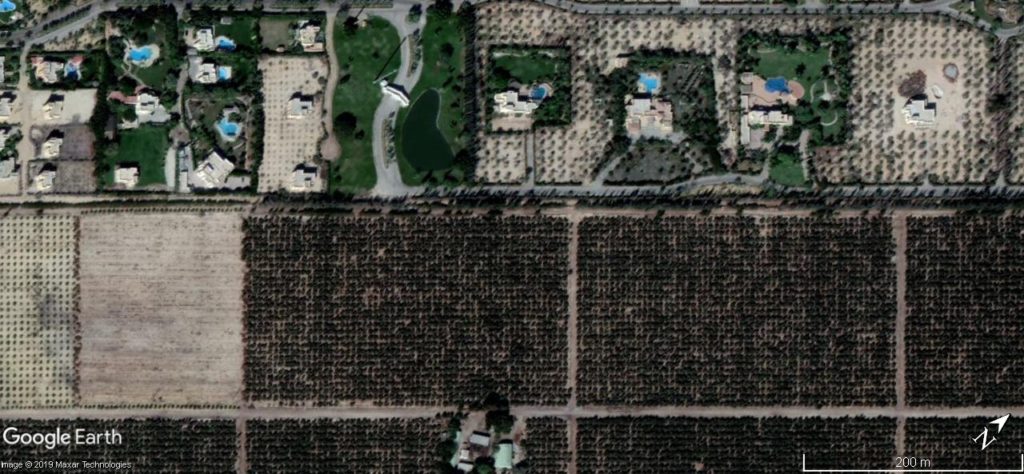

The highlight of which has been tens of thousands of acres of desert land sold on the condition of agricultural reclamation to companies and cooperatives that had not intention to do so. The more infamous of these are on the Cairo-Alexandria and Cairo-Ismailia highways, where construction for agriculture related buildings was only allowed on 2.5% of the land (with some exceptions to 7%), though because of their proximity to Greater Cairo, and the land’s relatively low price compared to the nearby New Cities, many plots have been turned into gated resorts (Figure 4). In 2016, the government agency originally in charge of distributing this land calculated LE67bn in illegal change of land use, from agricultural to urban, which it had only managed to recover LE204mn of as large scale developers refused to pay the fines,[12] or, they had simply sold the land on and the buyers objected to the fine.

Figure 4: Legally reclaimed desert land (bottom), and informal gated resorts on land designated for reclamation (top) on the Cairo -Alexandria highway. Google Earth, November 2018.

What is the Future of Informal Production?

The Construction Violations Reconciliation Law, was published last April, stipulating the conditional regularization of all informal buildings built up to that date. While all those built after that date will be regulated by the mainstream building law which stipulates demolition of any buildings constructed without a permit. However, given that this is the ninth such reconciliation law since 1956, and that the root causes of informal building remain unaddressed, it is hard to imagine that building informally will disappear any time soon.

Acknowledgements

Written by: Yahia Shawkat

Main Image: Basateen, Cairo. BEO.

Notes & References

[1] The Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics collects statistics on building permits form the local councils, and government housing from the ministry of housing on an annual (financial year) basis. The ‘Statistical Yearbook’ (Housing Chapter) has been used for years 2008 through 2015, while the recently introduced and more detailed ‘Nashrat Al-Iskan Fi Misr’ (Bulletin of Housing in Egypt) has been used for 2015/2016 through 2017/2018.

[2] Al-Akhbar, ‘Taftish Al-Iskan: 2 Million Wa 900 Alf ‘aqar Mukhalef Fi Misr’, 26 February 2018, http://archive.is/yakJL.

[3] Ministry of Electricity and Energy, ‘Egypt Electricity Holding Company Annual Report’ 2006/2007 through 2017/2018, http://www.moee.gov.eg/english_new/report.aspx. Subscribers labeled as ‘Residential’, in addition to a weighted portion of ‘Closed/postponed’ and ‘Zero Reading’ because of their significant numbers. These statistics represent all formal electricity subscribers whether through formal contracts, or semi-formal ‘coded meters’. They do not include unmetered connections or mumarsa, as they are bundled together in ‘Others’, which may include many non-residential users.

[4] Note: Ministry of Electricity data for 2016/2017 was inconsistent with older data, and therefore a total for that year has not been calculated.

[5] As the uprising happened in the middle of the financial year 2010/2011, that year has been omitted from the calculations, relying on the symmetry of the three years preceding and succeeding it.

[6] Ministry of Electricity reports show how the electricity companies receive more applications than they accept, while of those accepted, not all have electricity extended during the financial year. In 2011/2012 out of one million accepted applications, 880,000 had electricity extended. MoEE, ‘Egypt Electricity Holding Company Annual Report 2011/2012’ (Ministry of Electricity and Energy, 2012), 38, http://www.moee.gov.eg/english_new/report.aspx.

[7] In the 1986, 1996 and 2006 Census for Population and Living Conditions, ownership was enumerated into three categories: tamlik (ownership) through buying, milk (owned) through construction or inheritance, and hiba (gifted) most probably by fathers to their sons. The 2017 census merged the categories of ‘ownership’ and ‘owned’ and so a forecast was made for ‘owned’ using the last three censuses. CAPMAS, ‘Final Results of the General Census for Population and Housing Conditions for 2017’ (Cairo: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), December 2017), http://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/Publications.aspx?page_id=5109&YearID=19635.

[8] Yahia Shawkat, Al-‘Adala al-Igtima‘iya Wal-‘umran—Kharitat Misr, 2013, 47–48, http://blog.shadowministryofhousing.org/p/blog-page_2887.html.

[9] Built Environment Observatory, ‘Al-marhala al`ashera li-aradi al-iskan al-igtima`i: la-mazaya wal-`uyub’, 10 April 2019, http://marsadomran.info/facts_budgets/2019/04/1747/.

[10] Yahia Shawkat, ‘Sixty Years of Legalizing Informal Buildings in Egypt 1956-2019’, Built Environment Observatory, 10 October 2019, http://marsadomran.info/en/policy_analysis/2019/10/1805/.

[11] Ali Al-Moghazy, ‘Forced Informality: When Housing Rights and Building Laws Collide’, Built Environment Observatory, April 2018, http://marsadomran.info/en/policy_analysis/2018/04/1511/.

[12] Al-Ahram, ‘Ba‘d al-Ta‘addi ‘ala Alaf al-Afdina Min al-Ruq‘a al-Zira‘iya’, Al-Ahram, 6 March 2016, http://web.archive.org/web/20181213211254/http://www.ahram.org.eg/NewsQ/483467.aspx.