- Published on 10 October 2019

As part of the Built Environment Observatory’s series on the new Construction Violations Reconciliation Law, a law that is believed to have a massive effect on housing and cities in Egypt, we look back at sixty years of reconciliation capped by this, the ninth such enactment of this so-called ‘temporary’ law.

Introduction

Over the last six decades, hundreds of laws that govern urban planning and construction have been passed, progressively regulating every conceivable detail of our cities and the buildings within them, while stipulating fines and even jail terms to thwart any attempt to disregard the idealism that the laws promised. However, what we see today of Egypt’s built environment; organic self-built settlements, disparate skylines, and a general sense of urban chaos, are but the result of these ideal laws, or rather, their successive suspension through ‘temporary’ legislation that sought realism over idealism.

1956-1986 Legalizing Informal Subdivisions

Affordable informal housing flourished in the early 1950s, leading in 1956 to the enactment of a new law to freeze any demolition orders issued for buildings that contravened building legislation.[1] The 1956 freeze was exclusively for informal construction, especially that of taqsim mukhalif (informal subdivision) of privately owned land, usually agricultural land, and did not extend to informal construction on state-owned land, or that which contravened tanzim lines. It was a so-called temporary law that only froze decrees lodged against illegal building until the date the law was enacted, while it would continue to be imposed on infractions after that date. It was an emergency measure made due to the severe “homes crisis”, but acknowledged that the “leniency has encouraged many individuals to contravene these [planning and building] laws, and since the homes crisis has now abated, it has been decided to put a limit to this leniency.”[2] For reasons of public health, the law also allowed for the extension of formal infrastructure to the public areas in the new neighbourhoods – streets, plazas, gardens, for free, as well as to the private homes, though for a fee which would be paid for by the owners.

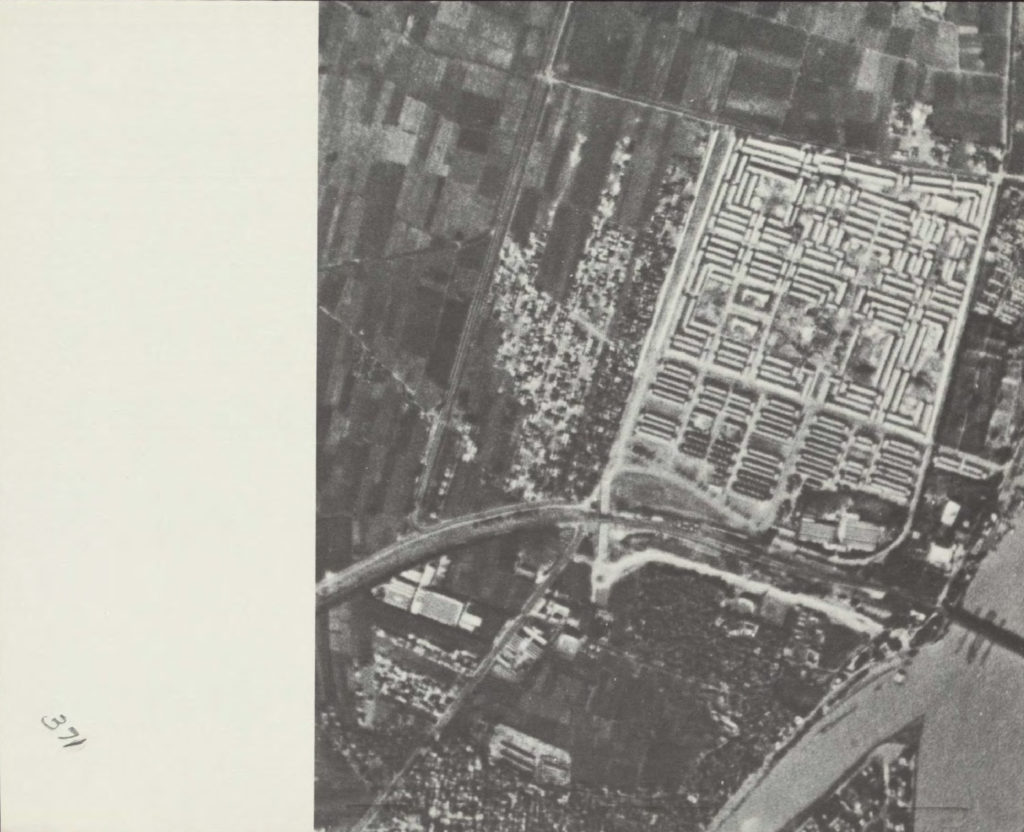

Figure 1: Aerial image of the Imbaba district in Giza in 1957, showing the state-built Workers’ Colony (right), constructed between 1947 and the mid-1950s, and informal housing that had started to be built on agricultural land to its west and south, no doubt benefiting from the legal amnesty of 1956.[3]

It wouldn’t be the only time that then president Gamal Abdel Nasser would issue the ‘temporary’ law, where it would be enacted another three times before his death in 1970.[4] Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, would bolster the construction and urban planning laws in 1976 in a bid to “keep up with urban developments, and confront the severe dilapidation of buildings where many are on the verge of collapse.”[5] Within five years this new law would be suspended with a new issuance of the reconciliation law,[6] very much in line with its forebears.

In 1982, president Hosni Mubarak would pass yet another updated building law, strengthening penalties even more while separating building and urban planning legislation as they grew more detailed.[7] But almost overnight, these laws would be suspended in 1984 and again in 1986,[8] legalizing informal subdivisions and construction.

Figure 2: Aerial image of the Imbaba district in Giza in 1966, showing the massive growth of informal housing from the previous image, most probably driving the amnesty of 1966. (See footnote 3).

1990-2011 Formal Electricity for Informal Buildings

The year 1990 saw a paradigm shift in the ‘temporary’ legislation when Cairo Governor Decree 75/1990 allowed the formal electricity to the `ashwaeyat (literally randomly built areas), though with no further legalization of the subdivisions nor the construction, a quasi-formalization. Three years later, the National Project to Upgrade Slums would target 1221 `ashwaeyat, with public utility and social services projects such as schools and clinics, while demolishing 20 of them because they were seen as unfit for upgrading.[9]

Figure 3: Aerial image of the Imbaba district in Giza in 1977, by now most greenfield west of the colony is built up, the newer homes awaiting the amnesty of 1981. (Image source: See footnote 3).

By the mid-2010s, the government had identified two forms of informal construction: the `ashwaeyat, which were mostly self-built settlements on private agricultural land, and the mabani al-mukhalifa (buildings in breach of the law), the informal building additions to formal buildings, as well as the completely informal buildings built in formal neighbourhoods. Cabinet Decree 129 of 26 October 2005 allowed the state-owned Egypt Electricity Holding Company to extend formal electricity to the `ashwaeyat, while Governors’ Council Decree of 1 November 2005 allowed of the same to the mabani al-mukhalifa. These orders came on the back of half a million requests by owners of informal buildings made to the electricity companies, and by 2011 almost 900,000 informal buildings would have formal electricity.[10] Those were all despite Mubarak issuing the Unified Building Law 119/2008 that clearly banned the extension of formal utilities to buildings constructed without a permit.[11]

2011-2019 Semi-formal Electricity

In the months following the January 2011 uprising, the ministry of electricity had received more than one million requests for formal electricity.[12] Within a year, 880,000 requests were honoured, though receiving semi-formal connections instead of the usual formal connections. The ministry had devised so-called ‘coded’ meters, meaning ones that used a numerical code for identification instead of the property owner’s name, where no contract would be made that may be used to formalize the construction process, leaving the door ajar in case the government would later move to demolish the buildings.

By 2016, the coded meters would be fully legislated stipulating that owners would be able to request formal meters if they received reconciliation permits from the authorities, or, the meters would be removed if a court ordered the demolition of the informal building.[13] A window of time for requests was also set for June 2018, where a total of 1.88 million would be made by then.[14] The deadline was later pushed to January 2019, adding even more requests.

Conclusion

Last April, parliament passed Construction Violations Reconciliation Law 17/2019, the ninth such iteration of this ‘temporary’ law since 1956 when it was first enacted. Given the history of informal building in Egypt, this won’t be the last.

Acknowledgements

Written by: Yahia Shawkat

Main image: Aerial view of Imbaba, Giza in 1966. Source: see footnote 3.

Notes and References

[1] From 1940 to March 9, 1955. Law 259/1956, Article 1. The date of amnesty would later be extended to June 20, 1956 according to Law 32/1958.

[2] Informal Subdivision Law 259/1956, Explanatory Note.

[3] Reinhard Goethert and Mohamed el-Sioufi, ‘Growth of an Informal Housing Area Over a Thirty Year Period – Case Study: Imbaba Sector’, in The Housing and Construction Industry in Egypt: Interim Report Working Papers 1979/80, by Joint Research Team on the Housing and Construction Industry Cairo University/MIT (USAID, 1980), 97–125, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNAAM424.pdf

[4] Informal Subdivision Law 29/1966, and Minister of Housing Decrees 826/1967 and 47/1968.

[5] Building Law 106/1976, Joint Parliamentary Committee Report.

[6] Informal Subdivision Law 135/1981

[7] Laws 2/1982 and 30/1983 amending Building Law 106/1976, and Urban Planning Law 3/1982.

[8] Informal Subdivision Laws 54/1984 and 99/1986.

[9] CAPMAS, ‘Dirasat Al-Manatiq al-‘Ashwa’Iya Fi Misr’ (Cairo: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), 2008).

[10] MoEE, ‘Egypt Electricity Holding Company Annual Report 2010/2011’ (Ministry of Electricity and Energy, 2011), 40, http://www.moee.gov.eg/english_new/report.aspx

[11] Article 62.

[12] MoEE, ‘Egypt Electricity Holding Company Annual Report 2011/2012’ (Ministry of Electricity and Energy, 2012), 38, http://www.moee.gov.eg/english_new/report.aspx

[13] Prime Ministerial Decree 886/2016, and Minister of Electricity Decree 254/2016.

[14] MoEE, ‘Egypt Electricity Holding Company Annual Report 2017/2018’ (Ministry of Electricity and Energy, 2018), 66, http://www.moee.gov.eg/english_new/report.aspx