- Published on 16 January 2020

The new Construction Violations Reconciliation Law is believed to have a massive effect on housing and cities in Egypt, if it is implemented. As part of the Built Environment Observatory’s series on the law, this article questions why parliament is seeking amendments months after passing it, and days before it was due to expire. The full analysis is followed by recommendations on how to improve it.

[This is a translation of an article written in November before Law 1/2020 was passed amending the reconciliation law.]

Introduction

There is a wide range of violations related to construction in Egypt that are regulated by a host of different laws, some of which accept reconciliation. For example, squatting, adverse possession and building on agricultural reclamation land (as change of land use) are all illegal, though the recent Law 144/2017 was issued to legalize a large number of violations. Building on old agricultural land is also illegal and the agriculture laws stipulate fines for violations. Another set of violations is that of the building law itself (Law 119/2008), that covers all things design and construction related: for example, building footprints, setbacks, heights, and structural and architectural design. For these, the Construction Violations Reconciliation Law 17/2019 (Amended by Law 1/2020) was passed in April to legalize most – but not all – of these violations, whether on urban land, agricultural land, or squatted land as long as it was legalized.

And the numbers are large. The Built Environment Observatory has tracked down 8.2 million housing units that have been built without a permit since 2007, comprising a phenomenal three quarters of housing production. But after five of the six months the law gave violators to put in reconciliation applications, only 32,000 building owners had done so, a drop in the ocean. It seems the law has hit quite a few snags that from a technical perspective, hinge on complicated procedures that local authorities did not have the time to prepare for. However, the main problem lies in its massive unpopularity with owners who found three insurmountable hurdles that parliament has not taken into consideration in the current round of discussions on amending the law.

The first of these has been the fact that the costs of reconciliation have been vague, but known to be high. The single largest cost is the fine for reconciliation itself, where only three of the 27 governorates have decided on them in the past five months. Structural reports stipulated by the law have been expensive to produce, while the Engineers’ Syndicate, entrusted with revising and approving the reports, has imposed high fees that are pegged to the fines.

The second hurdle has been establishing who is actually supposed to apply for reconciliation: the original owner/builder, or, the current owner/buyer in the cases where units have already been sold, something the law has kept vague. The latter would be like asking the buyer of a nonconforming product to pay the fine even though he or she have no responsibility for it, and are in fact, victims. Here we reach hurdle number three. Even if owners of units wanted to apply for reconciliation, they could not do so individually, because the law only allows for reconciliation by building, meaning that all owners of units must band up together to put in the application and pay the fines. Something that is nearly impossible to accomplish, as owners of condominium apartments have rarely been able to agree on the distribution of normal maintenance fees.

Since parliament is already discussing amendments to the Reconciliation Law, this presents a great opportunity to evaluate how the law has performed from the perspective of building and home owners, and to propose amendments to improve it.

What are Building Violations?

The Reconciliation Law opens with an article stating that “reconciliation can be accepted for works that violate the building laws.” Meaning that it covers only building and construction violations, where according to Building Law 119/2008, those held liable for them are only the original building owner as well as the contractor and supervising engineer if there was one consulted. Article 39 of that law stipulates applying for a permit for building construction, expansion, height additions, changes, supports, restoration or demolition, as well as external finishing. Therefore, any of these works not carried out with a permit, must apply for reconciliation.

But not all violations can be reconciled. First off there is a cut-off period where any violations after April 8th, 2019, the date the law was passed, would not be accepted (Art. 1). Another date, July 22nd, 2017, has been stipulated for buildings in rural areas constructed outside of, but contiguous to, village limits (cordon), as per aerial photographs conducted by the army (Art. 1). Going back in time, there is no start date for the violations, where the last similar law reconciling violations was passed in 1986, however it is not known how many violations were legalized by it.

Other violations that will not be reconciled are buildings that fail the structural integrity tests, those built on tanzim lines (public rights of way), modifications to heritage listed buildings, those that infringe on civil aviation ceilings or national security stipulations, and buildings constructed on state owned land unless legalized, as well as construction on protected areas such as heritage and Nile bank zones (Art. 1).

Recognizing a Building Violation?

The straightforward way to know is whether the building or parts of it (additional extensions, or floors, etc…) has a building permit or not. However, a number of local government archives were burnt in the wake of the January 2011 uprising, and building permits were lost. In the event no original copies were found with the original owners or architects, then a police report of an infraction, warnings or a demolition decree are the other official documents that can state that there has been a violation. Another way to find out if your building, or unit, is in violation is whether it has a formal electricity meter, with a contract with your name, or, if it has the temporary coded meter, that as its name implies, has a numerical code in lieu of the name so as not to give any tenancy rights to the user of that meter. Though we know from government officials that not all violations have been accounted for, as there is a large discrepancy between Ministry of Housing statistics (2.9 million buildings since the year 2000), and numbers we collected (8.2 million units since 2007), while coded meters have only been hooked up to 1.8 million units, therefore the law largely relies on self-reporting.

Reconciliation Process

According to Law 17/2019, applications for reconciliation should be submitted to the technical committees formed at the markaz (county), city or district levels, or, to the agencies that have jurisdiction over land (NUCA, TDA, etc..), which will issue their verdict on the reconciliation (Art. 4.) Once applications are accepted for submission, any legal charges will be frozen until a verdict on the reconciliation is decided. Those who have already received final court verdicts on their violations, stipulating fines or jail terms, can also apply and have the ruling temporarily suspended until a verdict is reached.

The application requires a large amount of paperwork as the law’s executive bylaws enacted by Prime Ministerial Decree 1631/2019 (Amended by PM Decree 936/2020) show, while an explanatory booklet has been produced by the Ministry of Housing to help explain the process. Some of the more important of the required documents are ones that prove ownership (deeds, utility bills), an engineering report on structural integrity, and documents that prove that the violation preceded the stipulated dates (police reports, utility bills, aerial photographs).

In the case of a positive verdict, a governor’s decree is passed allowing legalization of the constructions works and the dropping of any legal actions against it or suspension of court rulings. The reconciliation fine must then be paid in full, or, in three equal yearly payments plus interest after a 25% advance is paid (Bylaws Art. 11). According to Art. 6 of the law, the reconciliation decree is “a permit that removes the effects of the construction violations.” It would also allow for the property to be registered with the Real Estate Registration and Notarization Office.

In the event of a negative verdict, or, of non-payment of the reconciliation fine, the reconciliation application is rejected and legal actions against it are resumed (Art. 9). Rejected applicants can appeal the decision to an appeals committee within 30 days of receiving the rejection, where a verdict must be issued within 90 days (Art. 10).

Costs of Reconciliation

Applicants must pay for a number of procedures to meet all reconciliation demands, some of which are very expensive. These costs vary widely, while most governorates are yet to issue the values of the reconciliation fines in their areas.

Reconciliation Application

Applications themselves range between LE 125 to LE 5000 depending on the size of the building, and whether it is urban or rural (Bylaws Art. 4). For example, an owner of a two storey village house with a 100m2 footprint, would pay LE 125, while fees for a ten floor building on the same footprint, but in a city would be LE 2000.

Engineering Report

This is the costliest of the documents needed for reconciliation, is the engineering report which assesses the building’s structural integrity, as well as reports its size and features. The report must be prepared by a registered ‘consultant civil engineer’(istishari handasa madaniya)[1] and approved by the Egyptian Engineers’ Syndicate (Bylaws Art. 3). The government has not stipulated any limits on the costs of these reports, where some offices have quoted LE 10,000 for small buildings under six floors, though prices rise exponentially for taller buildings as costly core sampling is required to test the soil.

Engineering Syndicate approvals cost between 1.5-3/1000 of the estimated reconciliation fine,[2] starting at LE 500 per report, though for most, it could run into thousands of pounds.

Finishing of Facades

Article 6 of the Reconciliation Law stipulated that in addition to all other stipulations, buildings must be painted for a positive verdict. Depending on the area and number of facades, this stipulation alone will add tens of thousands to the reconciliation bill.

Reconciliation Fine

This can be the largest of the costs for most applicants, which the law devolved to the governors to decide within a range of LE 50 to LE 2000 per square metre (Art. 5). Hamlets and villages carry the lower fines, which rise in towns and then cities, especially provincial capitals. Also, within the cities themselves, fines have ranges according to the real estate value of the districts, as well as the heights of the buildings, and the street widths. Until writing, only four governors had issued cost decrees, two of which can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison between reconciliation fines in two governorates (LE/m2)

| Daqahlia | Qalubia | ||||||||

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Avg. | Less than 6 flrs. | 6 Floors + | Avg. | |||

| Urban | Capitals | 1000 | 800 | 600 | 800 | 300 | 400 | 350 | |

| Secondary | 800 | 500 | 300 | 533 | 250 | 350 | 300 | ||

| Towns | 600 | 400 | 200 | 400 | 150 | 200 | 175 | ||

| Avg. | 800 | 567 | 367 | 578 | 233 | 317 | 275 | ||

| Rural | Villages | 200 | 150 | 100 | 150 | 75 | 150 | 113 | |

| Hamlets | 175 | 125 | 75 | 125 | 50 | 100 | 75 | ||

| Avg. | 188 | 138 | 88 | 138 | 63 | 125 | 94 | ||

| Gov. Avgs. | 494 | 352 | 227 | 358 | 148 | 221 | 184 | ||

| Notes: The values are averages of a number of locations in each governorate Sources: Daqahlia Governor Decree 488/2019 & Qalubia Governor Decree 784/2019 |

|||||||||

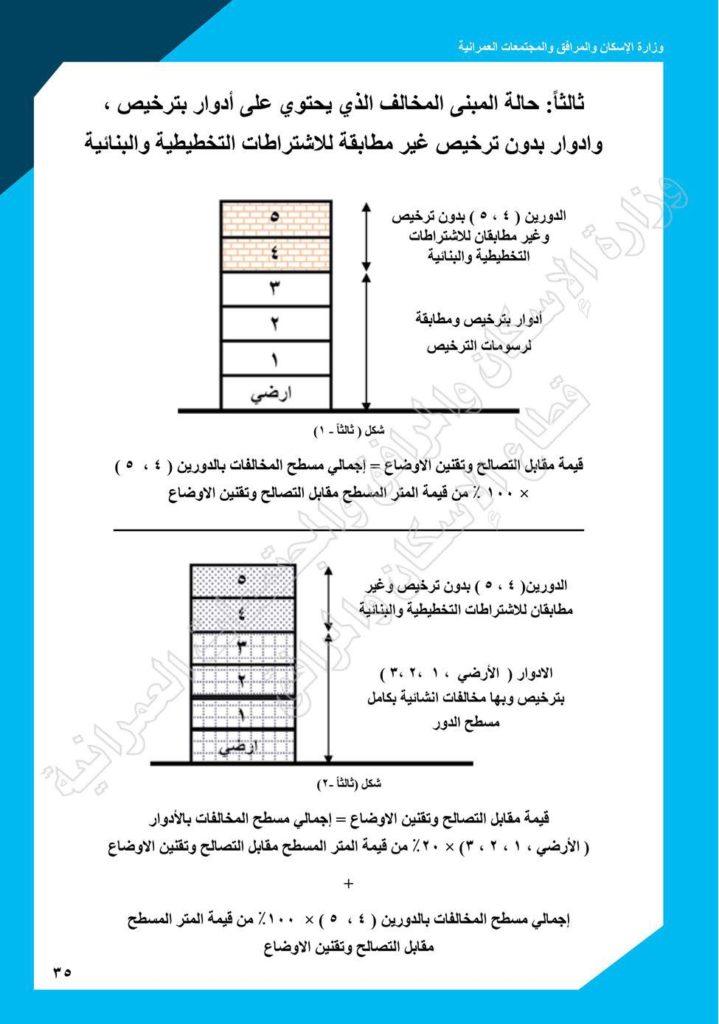

However, in certain cases these values, are not applied as is, and instead follow a range of between 5% and 100% of the stated value according to the type of violation. These include whether it was a violation of urban planning, architectural design, structural design, or use standards, or a combination of them (Bylaws Art. 7d). As they have proved very complicated to calculate, the Ministry of Housing later issued an explanatory booklet that used schematic drawings to show a number of possible permutations of building violations and how to calculate fines for each (Figure 1).[3] These are of course not exhaustive. Once a reconciliation decree is issued, the fine is payable, either the full sum on the spot, or, after paying a quarter of it, the remainder may be paid in three equal instalments over three years with interest (Bylaws Art. 11).

Figure 1: One of the many permutations of violations and how to calculate them as presented by a Ministry of Housing explanatory booklet (see text)

For example, an owner of a 150 m2 flat in the city of Mansoura, Daqahlia, that is built in violation of planning and construction standards as in Fig. 1, would have to pay LE 150,000 in fines based on 100% of the value of the per metre fine (LE 1000). On the other hand, the owner of a four story family home in a small village in Qalubia, where each floor is 100 m2, and only two floors do not follow structural standards, and the other two are fully in violation, would have to pay LE 12,000 in fines based on 20% of the LE 50 fine for two floors, and 100% of the fine for the remaining two.

Importance to Original Owner-Builders

It is here that the law faces its main snag, as its effect on, and thus its importance to the types of property owners varies quite significantly. The first type of owner are the original owners that initiated the construction process, and thus are held fully liable by the law for the violations. Any legal procedures in response to the violation would only mention them, their contractor and the supervising engineer if there was one. It is owner-builders that stand to fully benefit form the reconciliation law’s amnesty from prosecution which carries hefty fines as well as possible jail terms, which can also be dropped if final verdicts were issued. And while this type of owner-builder is mostly found in rural villages as well as peri-urban self-built communities, the informal real estate developers in cities have mastered the use of a kahul, a fall guy where all legal documents: land deeds, construction contracts, sale contracts, are in his or her name, and thus do not have a legal connection to the building and will not have any incentive to pay the fines. The kahul will also have no incentive to do so, as he or she will either be prepared to serve a jail sentence, or, will go into hiding.

Importance to Owners by Buying

This brings us to the second type of owners, who are those that bought apartments from original owner-builders, or even from secondary owners. For them, there is no legal obligation to reconcile, and so it may only be for some merely buying peace of mind. The reconciliation decree may allow them to fully register their homes with the Real Estate Registration and Notarization Office, as registration is not possible without a building permit. However, the land the building is built on has to be registered to the owner-builder as well, which may not be the case in an informal construction and many villages, while full registration is not very popular in Egypt, with estimates ranging between 3% and 10%,[4] as most rely on the courts to register the contracts, and not the property itself, through sihat tawqi’(signature validity) or siha wa nafaz rulings (validity of sale). In terms of the legality of utilities, up to 2011, the Ministry of Electricity had been ordered to hook up informal buildings with formal connections, which only leaves the almost 2 million (out of an estimated 8.2 million) informally built units using the semi-formal coded meters installed by the ministry between 2011 and 2018. Therefore, it is only a relatively small portion of buyers that may have a direct benefit from reconciliation.

While the reconciliation law states that legal proceedings would commence for buildings that have not received reconciliation decrees, it is not something that worries many owners as their sheer number has already been the reason forcing the state to issue a reconciliation law in the first place. Parliament has already admitted as much in the reconciliation law’s report stating that construction violations “have spread throughout the country… becoming a phenomenon that needs to be confronted… however, due to the difficulty in demolishing all the residential units because of their sheer number that has reached millions… they required a realistic solution and that is through legalizing their situation.”[5] So what will change now after closing the door on reconciliation applications with millions that have not applied? Well aware of this reality, in recent parliamentary discussions on amending the law, MPs suggested cutting off utilities for buildings that have not applied, sequestering them, or, raising utility fees threefold, all of which may very well be unconstitutional.

Importance to Residents

Regardless of whether residents of informally constructed buildings are owners, by building or buying, or tenants, one aspect of the reconciliation law proves important for those in larger buildings. Applicants must submit a structural integrity report that proves the building’s safety (Art. 4). In 2012/2013 Egypt witnessed 390 residential building collapses, where new buildings constructed without a permit represented less than 10% of the incidents, but a staggering 36% of the deaths.[6] In most of these cases, ‘towers’ of 10 storeys or more, were hastily built in the larger cities, especially Cairo and Alexandria, ended up collapsing on top of lower adjacent buildings. Therefore, it is important to establish the safety of these types of buildings.

Here, we find another drawback of the reconciliation law which does not stipulate whether structural inadequacies can be rectified, and the application resubmitted. Since many buildings may be repairable, it will be an inefficient measure to demolish them. On the other hand, will the government have the resources to demolish those buildings that really pose a threat? And on the other, will it provide alternative housing for the residents?

Conclusion: Recommendations for Meaningful Amendments

Truly implementable laws need to be just. High chances of success come only if the majority find them beneficial. However, if the sole reason of a law is to levy fines, then it will prove unpopular, and will be resisted, and this is what we find has happened with Law 17/2019. As the law is now in parliament again, discussing possible amendments, the following are recommendations for them based on our analysis.

Just Implementation

The key difference between housing units for personal use, and those for commercial gain must be acknowledged. The reconciliation law should exempt one residential unit per household, with a possible maximum size of 100m2, which is the national average. This can be achieved by digitising all reconciliation applications and comparing them to the real estate tax database that covers most of the real estate in Egypt, whether formally owned or not.

This step will go some way to untangling the problem of original owner versus owner through buying, as owner-builders may have built for their own personal use, while buyers could have bought for investment/speculation purposes. The sheer number of vacant units in Egypt, both formal and informal, means that many will indeed be taxed by the law, but not before upholding the social function of private property.

Reconciliation by Unit not Building

While unifying documentation by building will help in cutting down on administrative work, applications should be made by individual unit, though after proving the building’s structural integrity. This step will help increase applications, which in turn will help raise both security of tenure, as well as government revenue from the reconciliation. Whereas the current stipulation for reconciliation by building carries little advantage for the government and has proven a major obstacle.

Transparent and Lowered Reconciliation Fines

The higher end of reconciliation fines are exorbitant. Residents simply do not have the estimated LE 300bn ($18.9bn) the fines are thought to amount to. Even a quarter of that, in the case applicants resort to the instalment scheme, is equal to the entire private investments in real estate in one year.[7] Property buyers who spent their last pennies, and even went into debt to buy their homes will simply not have any extra funds to cover the fines.

Therefore, the top end of the fine should be cut from LE 2000 to LE 500 per square metre, so that total fines are somewhat realistic, while raising the possibility that they are collected. It is also imperative that all fines are made public before owners apply, so they are fully aware of the fees they should pay.

Revenue Spent on Repairs/Rehousing

While the majority of the projected revenue is earmarked for public housing and infrastructure, which is needed, this should also be amended. There are currently hundreds of thousands of dilapidated buildings that are on the verge of collapse,[8] in addition to the new informally built ‘towers’ that may fail the structural integrity tests. And since one of the main aims of the reconciliation law is the “preservation of the real estate assets”,[9] a large portion of the revenue must go to the repair of the dilapidated buildings, and the rehousing of those in buildings that are beyond repair.

Acknowledgements

Written by: Yahia Shawkat

Addition research: Ali al-Moghazy

Main image: An informal building, partially demolished by authorities. Giza, July 2019. BEO.

Notes and References

[1] While the bylaws state that the civil engineer must be an expert in concrete or metal structures, after complaints were made that many districts did not have these expertise, this stipulation was repealed by the Ministry of Housing. See: Committee on Reconciliation Law Clarifications, Circular of 17/9/2019

[2] Egyptian Engineers’ Syndicate Circular, 9/10/2019

[3] Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities, “Al-Qanun Raqam 17 Li-Sanat 2019 Fi Sha’n al-Tasaluh Fi Ba’d Mukhalfat al-Bina’ Wa Taqnin Awda’iha Wa La’ihatuh al-Tanfiziya: Istifsarat Wa Ijabatiha,” September 2019, 29–39, http://admin.mhuc.gov.eg//Dynamic_Page/637050972083779060.pdf

[4] In 2018, the head of the Real Estate Tax Authority stated that only 3% of properties were registered. Al-Mal, “Mu’tamar al-tatwir aláqari – Al-daraíb: 3% nisbat tasgil al-áqar fi Misr,” October 30, 2018, https://archive.ph/MLL9X. This is a marked fall from the 10% quoted in a large study conducted 20 years earlier. Hernando De Soto, “Dead Capital and the Poor in Egypt,” ECES/ILD, January 1998, http://www.eces.org.eg/publications/View_Pub.asp?p_id=5&p_detail_id=184

[5] Parliament. House of Representatives, “ِAl-Taqrir al-Khamis al-Mushtarak. Taqrir al-Lagna al-Mushtaraka `an Mashru` Qanun al-Tasaluh Fi Ba’d Mukhalafat al-Bina’,” May 1, 2019, https://issuu.com/youm7/docs/____________e8396f1faa78fb

[6] This report counted 31 buildings without a permit, resulting in 69 deaths. Shadow Ministry of Housing, EIPR, and TTC, “Why Are Houses Collapsing in Egypt?,” 2014, https://egyptbuildingcollapses.org/

[7] In FY 2017/2018 this amounted to LE 77.4bn ($4.9bn). CAPMAS, “Bulletin of Housing in Egypt 2017/2018” (Cairo: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), July 2019), 6.

[8] Around 3.2 million buildings need different levels of repairs, while another 100,000 were found irreparable and in need of demolition. CAPMAS, “General Census for Population and Housing Conditions for 2017 – Buildings and Units” (Cairo: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), December 2017), 52.

[9] Parliament. House of Representatives.