- Published on 06 September 2023

On the afternoon of October 12, 1992, a 5.9-magnitude earthquake struck Egypt for 60 seconds. Though it is classified as a moderate-magnitude earthquake, it toppled and damaged buildings in 17 of Egypt’s 27 governorates, causing over 500 fatalities, and leaving over half a million people homeless, thus becoming one of the worst 20th Century urban disasters to hit Egypt. Three decades on, it was surprising to find little information on it, so much so that many writings refer to it as the Cairo Earthquake, even though many other places were affected. This report maps the widespread impact of the 1992 Dahshur (Egypt) Earthquake. The disastrous effect of the earthquake is presented here in interactive maps as well as tables recording multiple sets of data disaggregated by governorate: damaged buildings, affected families, and deaths. In the absence of a comprehensive earthquake report, this data was compiled by reading the archives of contemporary daily newspapers over the ensuing three months after the disaster. That is in addition to local and international agency reports that covered different aspects of the earthquake (See Methodology for more).

How many buildings were damaged?

More than 129,000 residential buildings and houses were affected by the earthquake across Egypt (Map I, Appendix I). Over 12,000, or 12% collapsed or were so heavily damaged, they were identified to be demolished. Some 28,000 buildings, representing a quarter of the affected buildings, required significant repairs or partial demolition (usually of a floor or more). The remaining two thirds were found to need minor repair. The earthquake damaged buildings in 17 of Egypt’s 27 governorates, disproportionately affecting heavily populated governorates near to the epicentre, with Giza, where the epicentre was, seeing over two fifths of the damage (Map I).

Map I: Buildings damaged by the earthquak eb y governorate. Source: See Appendix I.

Urban Fallout

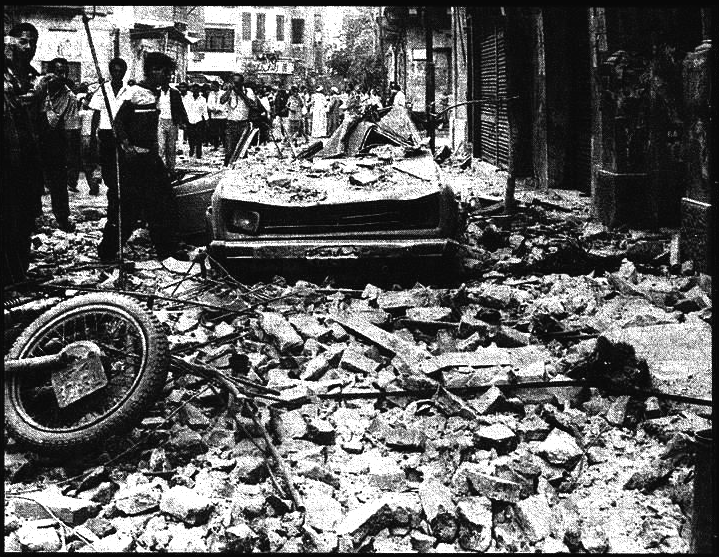

On an urban level, 40,000 buildings were affected in Cairo, representing over one third of all buildings. Overall, the Greater Cairo metropolis, Egypt’s largest urban agglomeration comprising Cairo, Giza city, and Subra al-Kheima in Qalubia, was the largest affected urban area. The majority of heavily damaged buildings were old masonry or stone load-bearing buildings not designed to withstand earthquakes.[1] The glaring exception, was the collapse of the modern reinforced concrete building in Heliopolis, which was attributed to the illegal addition of floors.[2]

The earthquake hit several historic sites across Egypt; 24 ancient archaeological sites and 140 Islamic and Coptic monuments were severely damaged, along with other 600 monumental structures that were slightly affected, according to official accounts.[3]

Figure 1: Rubble from a partially collapsed building litters a street in Cairo. Al-Ahram, October 13, 1992.

Rural Fallout

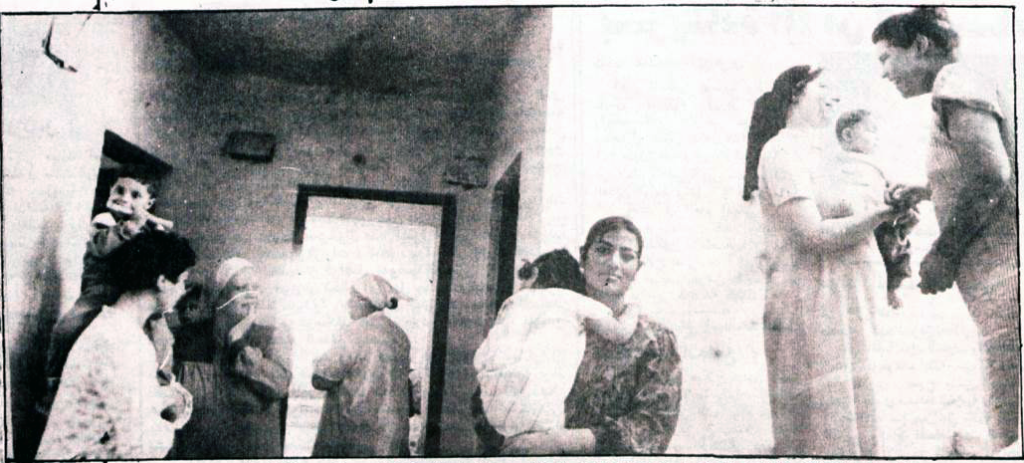

As the epicentre was in the Western Desert near the Nile’s western flood plain, rural areas near it were significantly affected. The villages of Giza were some of the worse hit, where 5292 houses collapsed or were damaged beyond repair, and 12,700 needed significant repair. Three villages were almost entirely levelled in Markaz Al-Ayyat,[4] for example, in the village of Abu Rewaysh, 90% of houses were damaged, with 30% completely destroyed.[5] Villages in north-eastern Fayoum were also close to the epicentre. In Markaz Tamiya, heavy damage was sustained in 5135 houses in the villages of Al-Rawda, Manshiyat Al-Gamal, Qasr Rashwan and Fanous.[6] According to earthquake expert teams that visited the villages later, most of the damage was “a result of direct shocks and large-scale destruction due to the collapse of adobe mudbrick buildings vulnerable to seismic forces.”[7]

Figure 2: A family who’s house collapsed in Markaz Al-Ayyat, Giza, seeks shelter near the canal. Al-Akhbar, October 15, 1992.

How many families lost their homes?

The earthquake led to the displacement of more than 100,000 families from destroyed or heavily damaged homes. Nearly 45 % of the homeless were in Giza – 86 % of those were village houses in rural Giza, followed by 44 % in Cairo – all urban, and 5 % in Fayoum – again almost all rural (Map II, Appendix II). The homeless had to seek shelter in the halls and rooms of youth centres in the cities, or crowd in with luckier relatives who did not lose their homes.[8] Over the ensuing week, centralised temporary camps were established by the army in Huckstep (Hayksteb), Helwan, and Al-Salam in Cairo,[9] and one in Imbaba in Giza.[10] These so-called ‘combined shelters’ were provided with services such as a mini-hospital, a pharmacy, and a police station.[11] However, the earthquake victims suffered from overcrowding within the tents, as each 20 sq.m. tent housed three families.[12]

The situation in rural Giza and Fayoum was even more dire, where the little or no emergency shelters were set up. Thousands of survivors of the villages in Markaz Al-Ayyat which were completely destroyed, as well as in Tamiya, set up tents made of reeds and bedsheets in the fields, streets and even on the railway tracks.[13] Only a small number of the homeless were sheltered in the youth centres of Al-Ayyat, Abu Hamila, Barnisht, Al-Atef, and Tahma.

Map II: Families made homeless by the earthquake by governorate. Source: See Appendix II.

How many families were rehoused?

With tens of thousands of families in tents, and on the streets, quick solutions had to be found. Within a week after the earthquake, President Mubarak promised that ”all affected families’ problems will be resolved in six weeks”,[14] meaning by early December 1992. The government then proceeded down three routes to attempt to rehouse the homeless.

Urban Rehousing

In cities most households were to be relocated to government-built housing units that were part of already ongoing social or cooperative housing projects, but that had not yet been delivered to their beneficiaries. In Cairo, more than 40,000 residential units were provided to families who lost their homes, most of which were in the Al-Slam and Al-Nahda housing estates (51%),[15] that were then in Cairo’s north-east fringe, while the rest were scattered in Al-Duweiqa and Al-Moqattam to the east, and Ain Helwan to the south.[16] Correspondingly, the Ministry of Housing provided 3952 new housing units for those displaced in Giza, in the eastern Cairo new settlement of Qatammia (today part of New Cairo).[17] It was similar in Fayoum city; 800 families were rehoused, and some shared apartments. In Qalubia, 859 out of 1384 families were relocated (Map II, Appendix II). However, it took over a year to rehouse the homeless, and not six weeks, and even then, by October 1994, 8000 families in Cairo and Giza remained displaced.[18]

It is important to note that despite large amounts of international financial aid offered to Egypt after the earthquake, rehoused families were expected to pay for their new homes, where only the 30% deposit was forgiven.[19] Months after families moved into the housing blocks, they received notices to pay monthly instalments at 6% compound interest over 20 years, in addition to overdue instalments from the date they had moved in.[20] Many of the families found the instalments unaffordable, let alone the overdue backpay, while a number refused to pay seeing that this was compensation for their lost homes.

Figure 3: A family moves in to Al-Salam housing estate, Cairo. Al-Akhbar, October 18, 1992.

Rural Rebuilding

Displaced families in rural areas did not receive housing units, but instead received between LE 500 and 1500 in cash aid to repair or rebuild their houses.[21] However, many complained that the sums were too low, leading some to sell agricultural land or take out loans to finance their rehousing.[22]

Urban Repair

The third rehousing effort was repairing damaged buildings that could be saved. This was also a slow-moving process that involved both the government and the building owners of over 80,000 buildings (Appendix I).[23] A year after the earthquake, this aspect of earthquake recovery had seen very little progress, where in Cairo only 48% of condemned buildings were demolished, and 30% of those needing urgent repair were addressed.[24] It remains unknown what the final outcome became.

How many people died?

According to the final Cabinet dispatch on the matter, published six weeks after the earthquake, a total of 561 people died and12,392 were injured.[25] An earlier dispatch with a lower total, showed that the deaths happened across nine governorates (Map III, Appendix III), or in half the total number of governorates affected by the earthquake. Giza, the governorate where the earthquake’s epicentre was located, was the worst-hit with 218 deaths, followed by Cairo which witnessed 205 deaths, and Qalubia 58. Together, these three governorates hold Egypt’s and the region’s largest metropolis, Greater Cairo, which at the time was home to 10 million people. Sadly, these three governorates were home to 87% of the victims.

Map III: Deaths by governorate. Source: See Appendix III.

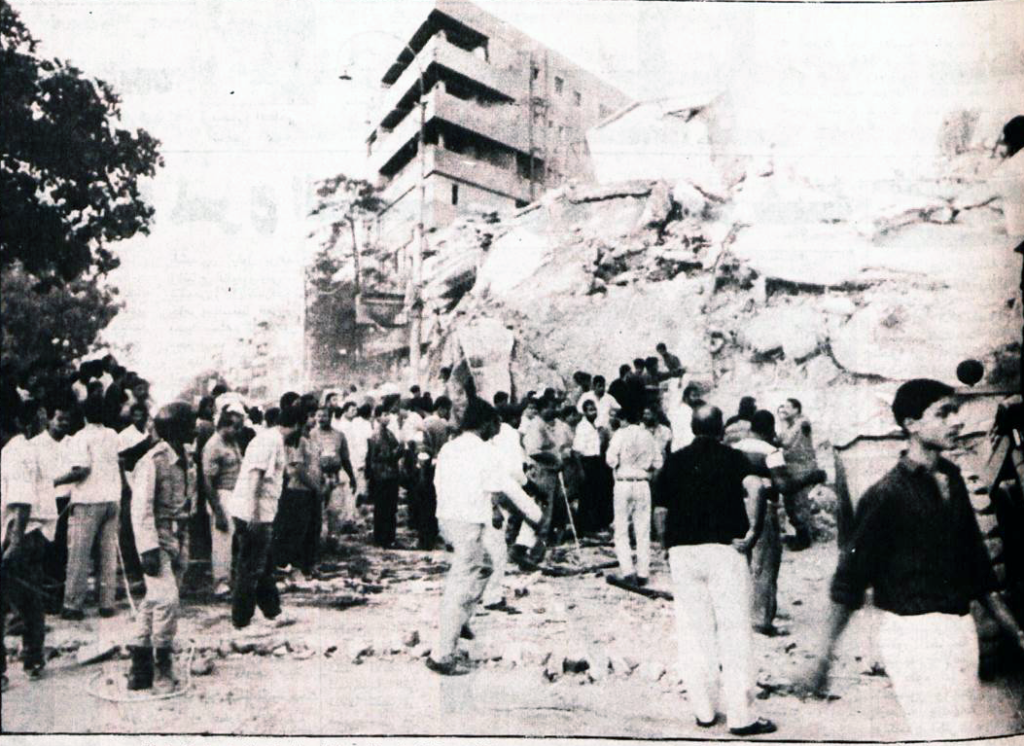

The earthquake flattened thousands of buildings of all kinds from small houses, to old derelict low-rises, to modern high rise apartment buildings. Even though not many high rises collapsed, one high rise building claimed a disproportionate number of lives: a 14-storey apartment building in the northern Cairo district of Heliopolis that the press called ‘imarat al-mawt (Building of Death). Designed and built as an eight-storey block of flats in 1983,[26] it was subjected to fatally excessive loads when the owner illegally added an extra six stories.[27] It took the local civil defence and international rescue teams 130 hours to remove building rubble in search of victims. They hammered through concrete debris and managed to only pull out six survivors.[28] One of them, Aktham Ismail, was famously found alive under the rubble 82 hours after the structure’s collapse, though he sadly lost his entire family. After the rescue operation ended, the Heliopolis building’s death toll stood at 72 people,[29] one third of the total deaths in Cairo, and more than ten percent of the total number of victims who lost their lives in the earthquake.

Figure 1: Searching for survivors beneath the rubble of ‘imarat al-mawt (Building of Death) in Heliopolis, Cairo. Al-Akbar, October 13, 1992.

Small rural houses were also not spared. The villages in Markaz Tamiya in Fayoum, 35 kilometres south of the epicentre, reported 47 deaths as entire houses disappeared into the ground.[30] Likewise, Markaz Al-Ayyat, the worst affected in rural Giza, recorded 57 deaths,[31] one quarter of Giza’s total deaths.

Earthquake victims were not just claimed by the building rubble, but also by managerial neglect. Around one fifth of the country’s schools were damaged by the earthquake. A total of 254 children were injured in Gharbia Governorate when their school collapsed.[32] However, many children also died during the panicked stampedes where hundreds of them were trying to escape the buildings. In the northern Cairo district of Shubra, 41 children died in stampedes in three schools, while Al-Mahalla Al-Kubra, in the Delta, held a shared funeral for 11 girls who died in a stampede at Abdel-Rahman Abu Zahra Preparatory School.[33]

Conclusion

As the region reels from recent extreme events: the earthquakes in Morocco, Turkey and Syria, the flash floods in Libya, and the port explosion in Beirut, the Built Environment Observatory emphasises that mapping of these disasters is an essential effort, after the initial emergency response, in order to assess their effect and be better prepared for any future events so that they do not automatically lead to urban disasters.

Methodology

As government agencies have not publicly published a comprehensive report or reports after the earthquake, data had to be manually gathered from a range of contemporary sources. Data was compiled on affected buildings, as well as affected or rehoused households from some primary, though mostly secondary sources that cited government figures. The primary source of data was official documents from local and international agencies (Institute of National Planning, General Organisation of Physical Planning, Japan International Cooperation Agency), then interviews and press releases of government officials found in state-owned press (Al-Ahram, Al-Akhbar, Al-Gomhuria, Ros Al-Yousef, Al-Mosawer), see bibliography. The effects on and the experience of households and individuals was found in interviews with affected families in both state-owned and political party newspapers. Where gaps or inconsistencies in the data were found, more recent though non-disaggregated data was pro-rated against complete, though outdated data.

To gather this data, all published news during the first three months after the earthquake (October – December 1993) was read, followed by more intermittent searches six months after the earthquake, and then on annual earthquake anniversary coverage one year (1993) and two years (1994) after the earthquake. As with any developing situations, numbers of affected buildings and rehoused families kept evolving over time, and only settled months after the event.

Affected Buildings

In a particular case study in rural Giza, we found the total number of affected buildings in a 1993 source, so we distributed disaggregate numbers based on relative percentages from an older source. We verified the quantities based on the average compensation paid out to affected families. For Fayoum, only a total figure was given for both urban and rural damage, therefore we allocated disaggregate numbers based on relative percentages from another earlier source that showed lower numbers of affected buildings.

Affected Families

In a number of governorates, only figures for affected buildings were published. Here we applied a 1:1 ratio assuming a minimum of one household lived in each building (a house) in two of the three categories of damage: collapsed, and significantly damaged. Where neither households nor building figures were found, for example in rural Fayoum, we divided the total financial aid paid out for home repair and rebuilding, on the stated average subsidy per household, to reach the total number of affected households.

Appendices

Appendix I: Affected Buildings by Governorate

| Source | Total | Simple Repair | Significant Repair | Collapsed/ Condemned | Governorate | Region |

| 129,242 | 80,247 | 33,722 | 15,468 | Total | ||

| Al-Gomhuria 4-5 December 1992, p.1 | 40,204 | 25,420 | 10,722 | 3,957 | Cairo | Greater Cairo |

| GOPP 1993 | 3,293 | 3,008 | 280 | 5 | Qalubia | |

| Al-Mosawer 29 October 1993, p.36 Al-Ahram 24 November 1992 |

68,446 | 38,520 | 21,038 | 8,888 | Giza | |

| Al-Ahram 20 October 1992, p.7 Al-Gomhuria 27 October 1992, p.9 |

28 | 0 | 28 | 0 | Alexandria | Alexandria |

| Al-Gomhuria 27 October 1992, p.7 Al-Gomhuria 16 November 1992 |

6,485 | 5,679 | 300 | 806 | Fayoum | Upper Egypt |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 126 | 31 | 53 | 42 | Assiut | |

| Al-Gomhuria 2 December 1992, p.4 | 1,347 | 1,283 | 23 | 41 | Beni Sweif | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 205 | 93 | 46 | 66 | Minya | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 848 | 559 | 126 | 163 | Gharbia |

Delta |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 1,319 | 906 | 236 | 177 | Sharkia | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 1,404 | 639 | 408 | 357 | Daqahlia | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 1,120 | 985 | 28 | 107 | Munfia | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 1,008 | 594 | 95 | 319 | Beheira | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 70 | 40 | 27 | 3 | Damietta | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 2,018 | 1,631 | 30 | 357 | Suez | Suez Canal |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 1,274 | 856 | 238 | 180 | Ismailia | |

| Al-Akhbar 19 October 1992, p.4 | 47 | 3 | 44 | 0 | Port Said | |

| 100.0% | 62.1% | 26.1% | 12.0% | |||

Appendix II: Affected Households by Governorate

| Source | Not Rehoused | Cash aid for repair/rebuilding homes | Rehoused by the government | Homeless | Governorate | Region |

| 13,310 | 44,245 | 47,043 | 104,598 | Total | ||

| Al-Ahly 12 October 1994 INP Report 1994, p.287 |

5,825 | 0 | 40,583 | 46,408 | Cairo | Greater Cairo |

| Al-Ahram 29 December 1992, p.11 | 525 | 0 | 859 | 1,384 | Qalubia | |

| Al-Ahly 12 October 1994 Al-Mosawer 29 October 1993 |

2,175 | 40,512 | 3952 | 46,639 | Giza | |

| Al-Ahram 20 October 1992, p.7 Al-Gomhuria 27 October 1992, p.9 |

56 | 0 | 0 | 56 | Alexandria | Alexandria |

| Al-Gomhuria 16 November 1992 Al-Shaab 11 December 1992 |

720 | 3733 | 800 | 5253 | Fayoum | Upper Egypt |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 96 | Assiut | |

| Al-Ahram 29 December 1992, p.11 | 0 | 0 | 182 | 182 | Beni Sweif | |

| INP Report 1994, p.49 | 246 | 0 | 8 | 254 | Minya | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 Al-Ahram 29 December 1992, p.11 |

230 | 0 | 59 | 289 | Gharbia | Delta |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 Al-Ahram 29 December 1992, p.11 |

281 | 0 | 132 | 413 | Sharkia | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 765 | 0 | 0 | 765 | Daqahlia | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 135 | 0 | 0 | 135 | Munfia | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 Al-Gomhuria 19 October 1992, p.7 |

64 | 0 | 350 | 414 | Beheira | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | Damietta | |

| INP Report 1994, p.43 Al-Ahram 25 November 1992, p.3 |

313 | 0 | 74 | 387 | Suez |

Suez Canal |

| Al-Gomhuria 20 October 1992, p.6 | 418 | 0 | 0 | 418 | Ismailia | |

| Al-Akhbar 19 October 1992, p.4 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 44 | Port Said | |

Appendix III: Deaths by governorate

| Deaths | Governorate | Region |

| 552* | Total | |

| 205 | Cairo | Greater Cairo |

| 58 | Qalubia | |

| 218 | Giza | |

| 1 | Alexandria | Alexandria |

| 46 | Fayoum | Upper Egypt |

| 0 | Assiut | |

| 5 | Beni Sweif | |

| 4 | Minya | |

| 12 | Gharbia |

Delta |

| 3 | Sharkia | |

| 0 | Daqahlia | |

| 0 | Munfia | |

| 0 | Beheira | |

| 0 | Damietta | |

| 0 | Suez | Suez Canal |

| 0 | Ismailia | |

| 0 | Port Said | |

| *Incomplete tally (see text), only one disaggregated by governorate. Source: Al-Ahram 21 October 1992 | ||

Acknowledgements

Written by: Yahia Shawkat, and Dina El-Mazzahi

Mapping support: Omar Sabet

Bibliography and further reading

Al-Ahram newspaper. Daily editions for 1992 and 1993 in PDF copies as archived on the Internet Archive.

Al-Gomhuria newspaper. Daily editions for 1992 in PDF copies as archived on the Internet Archive.

Egyptian Press Archive of the CEDEJ. Archival website covering news articles between the 1970s and 2000s.

Kamel, Sherif H. “Earthquake Damage Caused by District Differences in Urban Structure.” (General Organisation of Physical Planning, 1993).

Paul C. Thenhaus et al., “RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ON THE 12 OCTOBER 1992 DAHSHUR, EGYPT, EARTHQUAKE” (United States Geological Survey, 1993(.

JICA, “Report of Japan Disaster Relief Team (Expert Team) on the Earthquake in Arab Republic of Egypt of October 12, 1992” (Japan International Cooperation Agency, March 1993).

Abdalah, Wafaa Ahmed. “Natural Disasters in Egypt, Case Study of October 1992 Earthquake.” (Institute of National Planning (INP), 1994).

محمد نصر فريد, “تحليل بعض مشكلات مجتمع متضرري الزلزال بمدينة النهضة – حي السلام” (معهد التخطيط القومي: معهد التخطيط القومي (مارس 1995).

Benedict Florin, “Banished By the Quake Urban Cairenes Displaced From the Historic Center to the Desert Periphery,” in Cairo Contested: Governance, Urban Space, and Global Modernity, ed. Diane Singerman (American University in Cairo Press, 2009).

Footnotes

[1] Paul C. Thenhaus et al., “RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ON THE 12 OCTOBER 1992 DAHSHUR, EGYPT, EARTHQUAKE” (United States Geological Survey, 1993), pubs.er.usgs.

[2] JICA, “Report of Japan Disaster Relief Team (Expert Team) on the Earthquake in Arab Republic of Egypt of October 12, 1992” (Japan International Cooperation Agency, March 1993).

[3] “130 Islamic Monuments Closed off,” Al-Gumhuriyya, October 19, 1992, 6.

[4] “Forgotten People Face the Earthquake in Al-Ayyat,” Al-Akhbar, October 15, 1992, 9.

[5] JICA, “Report of Japan Disaster Relief Team (Expert Team) on the Earthquake in Arab Republic of Egypt of October 12, 1992.”

[6] “The Technical Committees Have Determined the Losses of Buildings in the Governorates,” Al-Akhbar, October 19, 1992, 4; “Today, Aid Is Disbursed to the Afflicted in Fayoum,” Al-Gomhuria, October 27, 1992, 7.

[7] JICA, “Report of Japan Disaster Relief Team (Expert Team) on the Earthquake in Arab Republic of Egypt of October 12, 1992.”

[8] “Sedqi in the Meeting of the Ministerial Committee to Face the Effects of the Earthquake: A Priority to Tackle the Results of the Earthquake While Following the Economic Reform,” Al-Ahram, November 24, 1992, cedej.bibalex; “The Delivery of 16,753 Apartments to the Affected People in Cairo Began on Monday, and in Giza from November 15th,” Al-Ahram, November 7, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[9] “Until Now, 4444 Families Have Been Accommodated in the City of Al-Salam, Al-Duwayqa, and Al-Jiza, and International Experts Have Examined Public Facilities,” Al-Ahram, October 21, 1992, cedej.bibalex; “Cairo Governor: 3,433 Families in the Shelters Began to Be Relocated on December 8,” Al-Ahram, November 25, 1992, 1.

[10] “A New Camp for the Armed Forces to Shelter the Victims of Imbaba,” Al-Gomhuria, October 24, 1992, 1; “The Victims of Giza: End of Shelters, but Overcrowding at the Dokki Youth Center,” Al-Gomhuria, December 4, 1992, 5.

[11] “Victims of the Earthquake in Giza: Solutions in the City, but the Deteriorating Situation Remains the Same in the Villages,” Al-Mosawer, November 6, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[12] “102 Families in 39 Tents,” Al-Gomhuria, October 26, 1992, 8.

[13] “Forgotten People Face the Earthquake in Al-Ayyat”; “Two Months after the Earthquake: The Afflicted of Fayoum Live in Cages of Reeds,” Al-Shaab, December 11, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[14] “Mubarak Confirms That the Problem of All Affected by the Earthquake Will Be Resolved, and They Will Be Relocated within Six Weeks,” Al-Ahram, October 19, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[15] Abdallah, “Natural Disasters in Egypt, Case Study of October 1992 Earthquake (Arabic)” (Institute of National Planning, 1994).

[16] “8 Thousand Families of the Earthquake Victims Are Homeless,” Al-Ahly, October 12, 1994, cedej.bibalex.

[17] “Buildings to Be Removed. When Will It End?,” Al-Gomhuria, January 4, 1993, cedej.bibalex.

[18] “8 Thousand Families of the Earthquake Victims Are Homeless.”

[19] “By Order of Cairo Governorate, Earthquake Victims Pay 106 Pounds Monthly and Retroactively for Accommodation,” Al-Wafd, December 17, 1993, cedej.bibalex.

[20] “The Truth About Evictions from the Housing Shelters,” Ros Al-Youssef, October 18, 1993, cedej.bibalex.

[21] “After a Whole Year: The October Earthquake Bill Is under Regard,” Al-Mosawer, October 29, 1993, cedej.bibalex; “Fayoum is judging itself,” Al-Gomhuria, November 16, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[22] “Two Months after the Earthquake: The Afflicted of Fayoum Live in Cages of Reeds.”

[23] “The State Covers the Costs of Major Renovations and Demolition of Homes through Contracting Companies Specified for Each Neighborhood,” Al-Ahram, October 24, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[24] “A Full Year Later: October Earthquake Invoice under Calculation,” Al-Mosawer, October 29, 1993, cedej.bibalex.

[25] “There Is Not a Single Egyptian Person Who Was Affected by the Earthquake on the Street Now,” Al-Ahram, November 1, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[26] “Investigate Who Is Responsible for the Death Building,” Al-Akhbar, October 21, 1992, 1.

[27] “EERI Earthquake Report” (Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, December 1992).

[28] “The Strangest Stories of Survivors in the Building of Death: Khaled’s Mother Tells the Details of 9 Hours in the Face of Death,” Al-Akhbar, October 15, 1992, 4.

[29] “Finish of Removing All the Rubble: 72 Victims, the Total Number of Martyrs of the Death Building,” Al-Ahram, October 18, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[30] MARTIN DEGG, “The 1992 ’Cairo Earthquake’: Cause, Effect and Response,” DISASTERS 17, no. 3 (1993): 231; “Fayoum is judging itself,” Al-Gomhuria, November 16, 1992, cedej.bibalex.

[31] Al-Akhbar, October 15, 1992, 9.

[32] “The Technical Committees Have Determined the Losses of Buildings in the Governorates.”

[33] “A Shared Funeral for 11 Girls in Al-Mahalla,” Al-Gomhuria, October 20, 1992, 9.