- Published on 12 April 2020

As Egypt largely shuts down to battle the spread of the novel coronavirus, millions of jobs are at risk, as in many other countries, though weak labour laws and a significant informal economy exacerbate the situation.[1] Many businesses have either cut salaries, delayed them, or laid staff off as their revenue has dwindled. Even more at risk are the millions of informally employed, especially house cleaners, day labourers and street sellers, whose livelihoods have all but evaporated. The biggest single casualty of a perceptible decline in income is rent or mortgage instalments, which if left unpaid, will put hundreds of thousands at the risk of eviction and homelessness if comprehensive measures are not quickly enacted.

The Egyptian government has already taken some steps to support individuals’ loss of income, the largest being a one-off cash payment to up to 1.4 million irregular workers.[2] That is in addition to rescheduling mortgage debts. While these have been important steps, official statistics urge the expansion of social support to economically precarious families, to both ease some of the burden, but more pertinently, encourage as large a portion of Egypt’s 100 million people to stay at home.

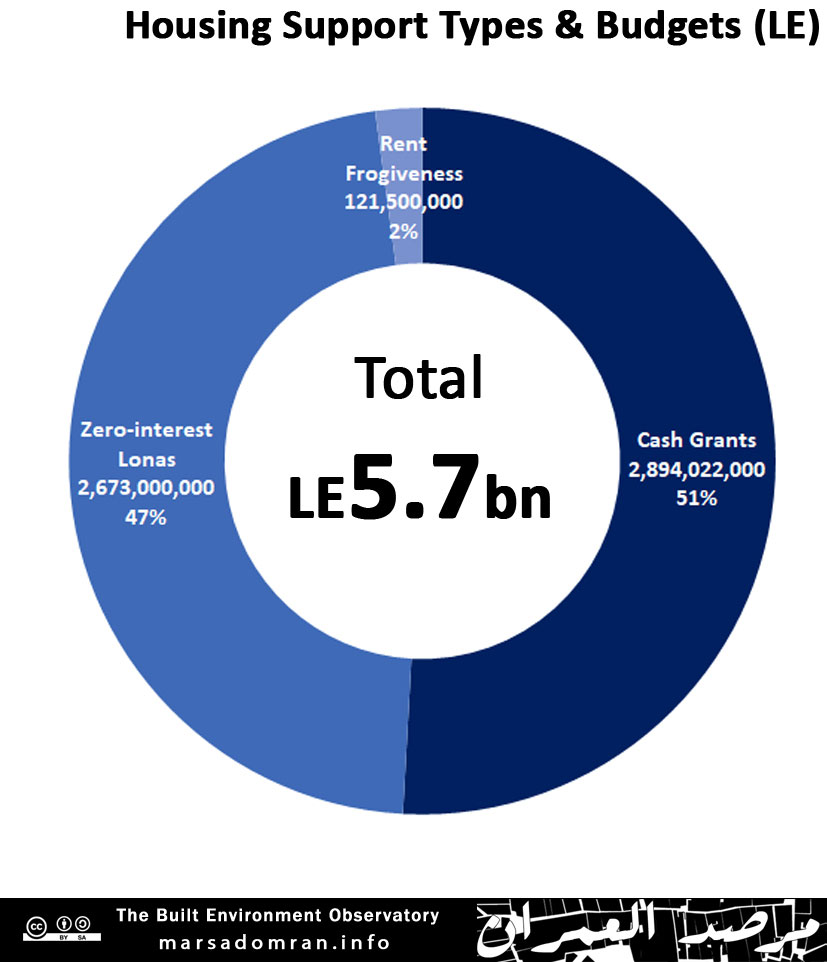

In this draft recommendation, we propose a programme to address around 1.7 million low and middle-income renters and mortgage payers (Social housing). This recommendation sets out a plan of LE 5.7 billion in aid, divided into grants to low income renters and mortgage payers (LE 2.9bn), zero-interest loans to middle income renters (LE 2.7bn), and rent forfeits from government landlords (LE 122mn). This represents less than 6 percent of the LE 100bn government aid package to fight the disease, while at the same time addressing a key component of the measures taken to halt the spread of the deadly virus, and that is ensuring that the most vulnerable still have a home to stay in during the lockdown.

Executive Summary

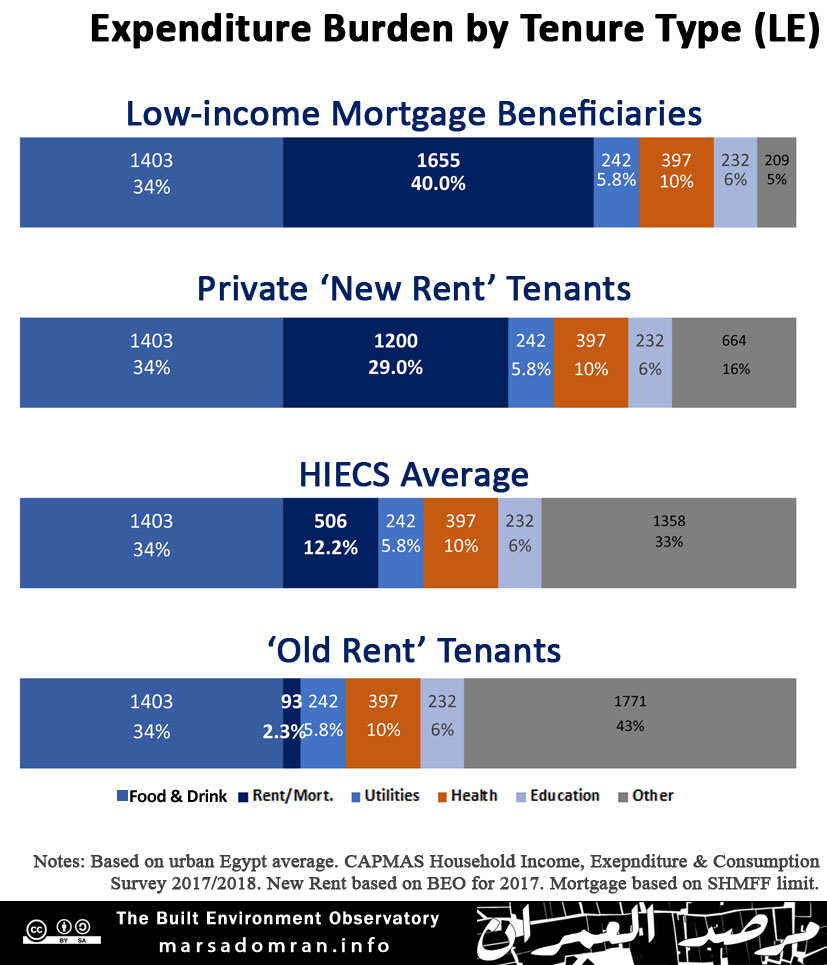

Current market rent (New Rent) values average 29 percent of urban households’ expenditure, which is a high burden in Egypt, especially compared to owners and rent control (Old Rent) tenants whose burden is around 6 percent. For low-income mortgage beneficiaries in social housing, this rises to 40 percent of income. Most of these households would not have savings to see them through any loss in income, putting them on a fast course to default and eviction.

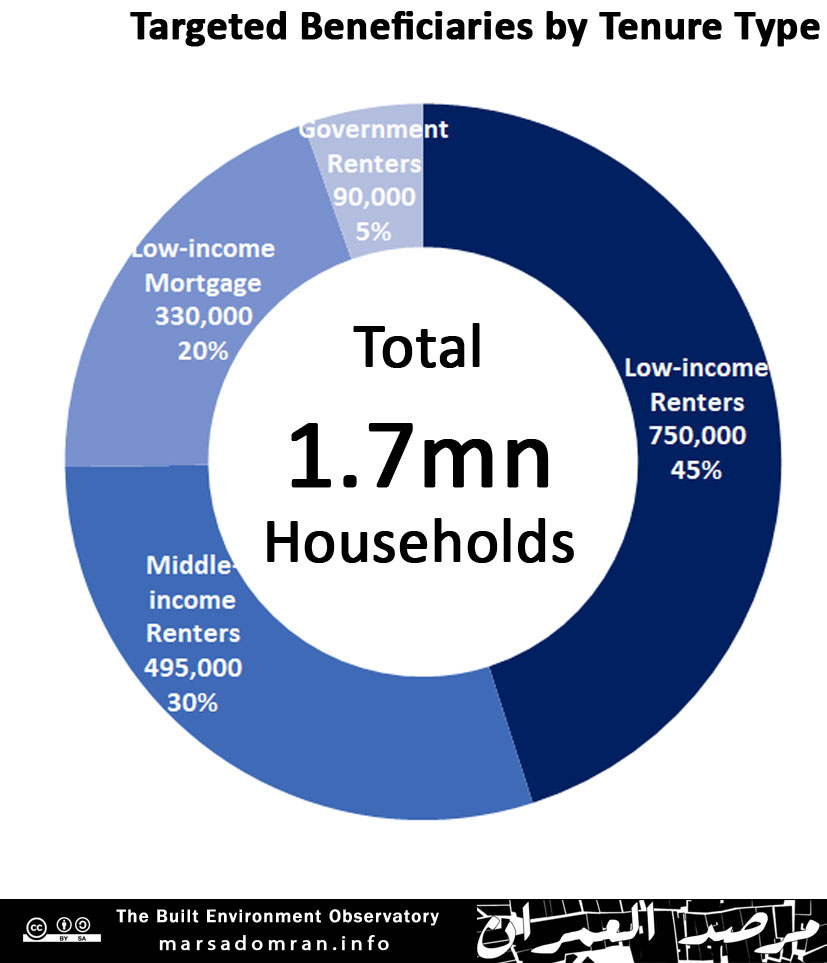

Here, approximately 1.7 million of the more vulnerable households have been divided into four groups (Figure 1), each depending on their needs to better target support:

- Group 1: Tenants of government housing. Almost 90,000 poor and low-income families that have been relocated to these estates as part of slum clearance projects.

- Group 2: Low-income New Rent tenants, that make up approximately 750,000 households.

- Group 3: Middle-income New Rent tenants, that make up approximately 500,000 households.

- Group 4: Low-income mortgage beneficiaries of around 330,000 households.

Figure 1

.

The financial aid programme aims to support these households over a duration of three months, that may be extended if lockdown measures are extended. Here three forms of aid have been proposed totalling LE5.7bn (Figure 2 ).

- Government agencies forfeit rents of tenants, worth an estimated LE122mn.

- Cash grants made out to low-income New Rent tenants, and low-income mortgage beneficiaries totalling approximately LE2.9bn.

- Zero-interest loans to middle-income New Rent tenants of around LE2.7bn.

In addition to financial support, we recommend the freezing of all evictions for at least three months, as well as the extension by three months of any contracts that end during the lockdown if tenants have not already found alternative housing.

Figure 2

.

Inelastic Rent/Debt Burden

Housing expenses make up the second largest expense for the average urban Egyptian family, claiming 19 percent of total spending where 12% is spent on rents and 6% on utilities and maintenance (Figure 3). On average, it comes a distant second to food that eats up 34 percent of expenditure. But this general average is largely misleading as the Household Income, Expenditure and Consumption Survey (HIECS) includes owners and those benefiting from low value rent control, known locally as Old Rent. Once average market rents are taken into consideration, where our study put them at LE 1200 (EUR 69) a month in 2017,[3] the rent burden for New Rent (uncontrolled rent) tenants climbs to 29 percent of their spending. For beneficiaries of subsidized low-income mortgages for social housing, this rises further to up to 40 percent of their income, the maximum allowable by the Social housing and Mortgage finance Fund (SHMFF). By comparison, Old Rent tenants pay only 2.3 percent of their income on rent, and free hold owners pay nothing.

Figure 3

.

In Egypt, renting is probably more representative of lower income households that did not have the money to build or buy their own homes. This means that tenants and low-income mortgage payers are economically precarious compared to owners and Old Rent tenants for the following reasons:

- Threat of eviction with homelessness or overcrowding in case of default.

- Rents and mortgage instalments are large inelastic payments that cannot easily be renegotiated or rescheduled (see more about mortgage initiative below).

- High concentration of low-income and poor households as tenants and mortgage payers. Since payments based on income and not wealth, they will also have less if any savings to see them through an income crisis.

- Absence of government or NGO aid programmes to support tenants and mortgage payers in case of default.

- New Rent tenants currently make up 12 percent of urban households,[4] or around 1.5 million households comprising six million people. Low-income mortgage beneficiaries are around 320,000 families, or roughly 1.3 million people.

Mortgage Rescheduling: Delaying the Problem

The Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) enacted a six-month debt delay in late March 2020 for mortgage payers among others, which is a debt rescheduling facility that incurs interest and not a cost-free delay.[5] Based on this, the Al-Ahly Mortgage Company offered two alternatives to mortgage payers.[6] The first was the full cash payment of the six delayed mortgaged payments immediately after the six months passed on September 17th, 2020. For a beneficiary that is already paying two fifths of his or her income on instalments, while facing any drop in income over the course of the next six months, paying a significant amount of cash in one go is simply unfeasible.

In the second option, mortgage payers would have their 10 to 20-year terms extended by six months where the additional payments would incur the interest that would have been due then had the contract extended that long, i.e. the highest interest on the schedule. Here it is impossible to ascertain how this would impact mortgage payers a decade or two from now, especially that an overwhelming majority are barely a year or two into their terms. Some maybe retired by then and their pensions would simply be too little to cover the extra payments. Overall, where one option is unrealistic, the other carries a high degree of uncertainty for beneficiaries.

Tenant and Mortgage Payer Support

An urgent, multi-dimensional support programme could not be more needed, covering different residents by priority and need.

Low-income Government Renters

Government agencies currently have at least 80,000 tenants that have recently been resettled in new housing estates such as Asmarat in Cairo,[7] as part of its slum clearance projects. In addition, around 6000 families benefited from rented social housing. The average rents of LE 450 (EUR 17) seem meagre, but some have been evicted before because they could not pay them, as residents of these estates are disproportionately poor.

- Measure: Forgiving three months’ rent tenants.

- Scale: Approximately 90,000 households comprising 360,000 people.

- Cost: With monthly rents averaging LE 450, approximately LE 116 million (EUR 6.8mn), or 0.1 percent of the LE 100 billion (EUR 5.8bn) corona emergency aid package.

- Source: Municipal budgets, the Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF) and the SHMFF.

Low-income Private Renters

Extension of cash support equal to the monthly rent of all private tenants whose rents are below the local average values. These would easily represent low income households, and the values of their contracts would prove their need, as opposed to more complicated and inaccurate procedures to establish income levels symptomatic of a largely informal labour corps, where only 57 percent work with a proper contract.[8]

- Measure: Three months’ rent-aid for tenants renting at or below the average local rent.

- Scale: Approximately 750,000 households comprising three million people.

- Cost: Assuming rents would average LE 900 (EUR 52) a month, the required aid for three months would be in the region of LE 2 billion (EUR 115mn) or around 2 percent of the national aid package.

- Source: SHMFF surplus from deferred housing allocations as well as construction due to the lock down.

Middle-income Private Renters

Loans for middle-income families (that rent at above the local averages), who would be with considerably less precarious jobs.

- Measure: Interest free loans from commercial banks, administered by SHMFF to cover up to three months’ rent. A cap of double the average rents (around LE 2400), could be set, with generous repayment windows of up to three years.

- Scale: If we assume one third of renters to be middle-income, then 495,000 households comprising two million people.

- Cost: Estimated LE 2.2 billion (EUR 120mn), based on an average rent of LE 1800 per month.

- Source: Surplus from the Central Bank’s Low Income Mortgage Initiative due to deferral of regular housing beneficiaries.

Low-income Mortgage Beneficiaries

The Activating the mortgage payment guarantee by the SHMFF for low income beneficiaries that cover mortgage payments for up to three months as per the Social Housing and Mortgage Finance Law 93/2018.[9] This should expand to include inability to pay due to significant decrease or loss of income.

- Measure: Guaranteed instalment payments for low-income mortgage beneficiaries for up to three months based on request.

- Scale: Assuming all beneficiaries are at risk since they fall in the low-income category, then approximately 330,000 households,[10] comprising 1.3 million people.

- Cost: Assuming an average mortgage instalment of LE 900 per month,[11] and all beneficiaries request aid: LE 869 million for three months.

- Source: SHMFF budget for mortgage subsidies.

Eviction Freeze

Freezing any evictions for three months in order to provide housing security for existing tenants, as well as extending any contracts that are set to expire by three months if tenants had not already secured alternative homes.

Conclusion

In the end, these measures are all implementable, with existing infrastructure and funds in place to do so. They also benefit residents in need directly, circumventing more bureaucratic and lengthy procedures that aim to support businesses, where weak oversight and labour informality would hinder attempts to ensure the support reaches employees.

Acknowledgements

Written by Yahia Shawkat and revised by Omnia Khalil.

Notes and References

[1] Amr Adly, ‘The Pandemic Could Transform Informal Labor in the Global South – Bloomberg’, Bloomberg, 24 March 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-03-24/the-pandemic-could-transform-informal-labor-in-the-global-south

[2] While 1.9mn people registered with the programme, 500,000 had their application rejected. State Information Service, ‘Manpower Min.: Irregular Workers to Get Their Monthly Allowances as of Monday’, 11 April 2020, http://archive.is/z9Thr

[3] Built Environment Observatory, ‘Egypt State of Rent 2017’, February 2018, http://marsadomran.info/en/facts_budgets/2018/02/1410/

[4] Ibid.

[5] Central Bank of Egypt, ‘Circular Dated 22 March 2020 Regarding the Explanatory Memo of Postponing Credit Instalments for 6 Months’, 22 March 2020, http://archive.is/huzom

[6] Al-Ahly Mortgage Finance, ‘Benefitting from the Instalment Delay Initiative’, accessed 3 April 2020, http://archive.is/GLgNC

[7] Egypt Today, ‘Rawdat Al-Sayeda: Transforming Slums into Better Communities’, 26 May 2019, https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/2/70839/Rawdat-al-Sayeda-Transforming-slums-into-better-communities

[8] CAPMAS, ‘Annual Bulletin of Labour Force 2017’ (Cairo: Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), 2018).

[9] Articles 9 and 10e.

[10] As of December 2019, there were 306,000 beneficiaries. If social housing was allocated at the same rate, then over the first two months of 2020 another 24,000 beneficiaries would have received their housing. SHMFF, ‘Social Housing and Mortgage Finance Fund Performance Report Till 31/12/2019’, 2019, http://archive.is/AFZPl

[11] With monthly household incomes for beneficiaries averaging LE 1900 (SHMFF.) and a limit of 40 percent instalment ratio, then the average starting instalment would be LE 760. And since allocations have started four years ago, then average mortgages would be incurring and addition two years’ interest of 14 percent.