- Published on 26 June 2018

As parliament edges closer to liberalising rent control in Egypt (known as Old Rent), the Egypt State of Rent series looks at the problems behind it and possible equitable solutions.

To read other articles in the State of Rent Series, click here

Introduction

For more than seven decades, rent was controlled in Egypt under the name “old rent”.[1] In 1996, a new rental law was issued which resulted in a housing market that is free of any control on rental prices for the new units and the vacant one.[2] The new rental law ensured some justice to the owners and the renters, though the rent is considered to be expensive in some neighborhoods compared to the annual income of families. The absence of any control to the market prices for the new rents made the majority of renters to complain as their incomes cannot keep up with rises in rent..

In 2017, 39% of incomes were spent on rents, which is high

For more see: Egypt state of Rent 2017

Despite of all the complications in the “new rent” law and its implementations issues, it is still incomparable to the complications of the “old rent” law. Over one and a half million families still have “old rent” contracts, which has led owners to pressure the government and parliament calling for an abolition of the law or some serious reforms to its articles. The parliamentary Housing Committee proposed many drafts to change the law over the last few years, yet no decision has been taken[3]. The amendments include to abolish the “old rent” law, and to give the renters a period of ten years—whether for residential or commercials uses—to vacate the units[4].

In this article, we question whether the “old rent” law is unjust only for the owners, and who would be the victims of its abolition? We interviewed owners and renters to understand the socioeconomic consequences of the abolition, as well as listening to renters and owners’ suggestions to more just changes. This article also discusses the “old rent” law from a spatial justice perspective, especially in light of the social function of private property and how we would reach a solution that would be just to the different parties. Our interviews took place with many people who live in different neighborhoods in the Greater Cairo Region, in order to have a spectrum of opinions.

Renters welcome a just solution

Hani is a resident of the Abbaseya district, who lives in an apartment with his mother., His grandfather had rented their home in the 1920s when he got married. In 1975, Hani’s father got married in the same apartment, and Hani himself has lived there since he was born[5] The building is 6 floors, with 3 apartments per floor. Hani and his mother live at the ground floor, in an apartment that faces the landlord’s. The doorman collects the monthly rent, that is 4 Egyptian pounds (EGP) (about $0.23).[6] Hani feels embarrassed each month paying this amount of money, while he and the other renters pay for any costs which are required for maintenance, small or big. They do not ask the landlord to contribute due to the low-value of rent they pay.

Hani thinks that it is not just for the landlord to be paid 80 EGP per month ($5). He believes that the situation is not just at all, he tried to think of many solutions that the law may include. He thought of paying a rent that would be half of the “new rent” value, like 1000 EGP($56.5) that is not expensive to the families, and which will ensure for the landlord 17,000 EGP($960.5) monthly, which isn’t a bad income.

We also met with Salma who lives in Dokki with her mother, sister, and brother. They have a big apartment of 200 square meters compared to modern residential units in Cairo. In 1962 when her grandfather rented the unit, which her father inherited. The building is 6 floors, each floor has 4 units. Some years ago, the landlord decided to add 4 more floors. All of the new residential units were sold or followed the rent values of furnished flats or “new rent” law. A few years ago, Salma’s father passed away, that is when the landlord decided to ask them for one year of rent in advance in order to prove to them that he will not kick them out according to the law. As the rental contract can only be bequeathed once, which had already happened when her grandfather died.

Salma’s family pays 6 EGP—$3.5 per month, that is the amount listed in the original contract. In addition, Salma’s family pay another 50 EGP as monthly wage for the doorman. Like Hani’s family, Salma and her neighbors are taking care of all the maintenance expenses in the building. Each family bought a small pump for the water to reach to their apartment as the water pressure is low in the neighborhood. Salma always thinks that the situation is unfair to the landlord, though according to her he is a rich man.

The landlord owns the building, and his brothers own the next-door building. The landlord does not live in the building, instead he lives in another building in the same neighborhood. Since the 1990s, Arab Gulf tourists started renting apartments at Salma’s building during the summer, paying thousands of times more than what Salma pays. There are also many shops at the ground floor of the building which pay very high market rents because it is a high-price area for shopping. The landlord works in construction, and two years ago he refused to sell the apartment to Salma’s family for 300,000EGP ($16,950), as he wanted 400,000 EGP, but basically, was not interested in selling.

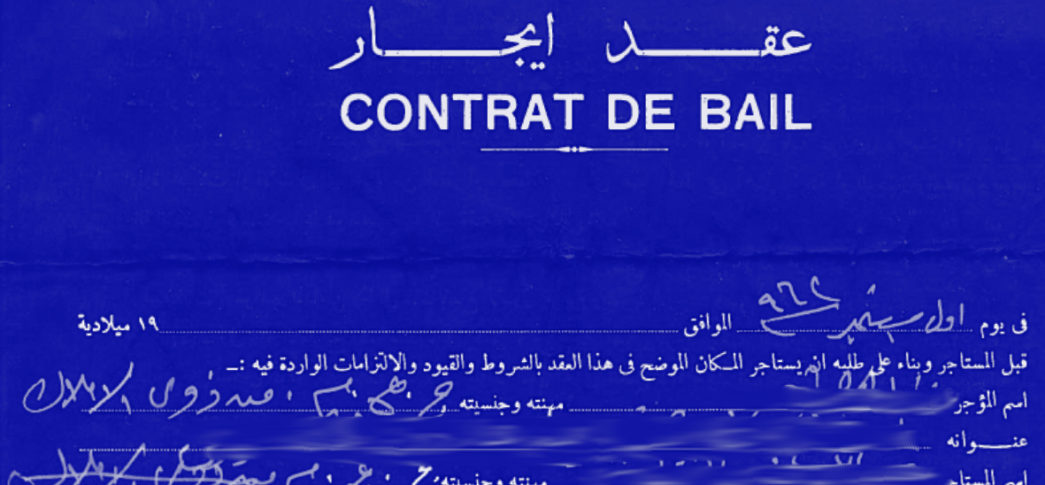

Figure 1: An Old Rent contract made out in 1962

The monthly income of Salma’s family is around 8000 EGP ($452) per month. It is impossible that they would pay 3000 EGP for rent. Salma thinks that the rent could be related to levels according to the electricity bill which she sees as a reflection of income; the higher the consumption, the higher the rent. For Salma, the rent can be affordable if it could be something in between 1000-1500 EGP monthly. She also suggested that the contracts be modified to 59 years instead of life-time, with a reasonable annual increase.

This last provision actually exists with some residential units in Egypt that neither follow the “old rent” law nor the “new rent” law. Instead they are a long-term lease—up to 59 years and are called ‘aqd maftuh (open contract). In Maadi, Anas rents a flat with a 59-year contract in a building that was built in 2006. The monthly rent is 700 EGP ($39.5), with a 1% annual increase. The apartment was fully finished by a former renter who took key money from Anas when he left the flat as compensation for the work he invested.

The building was built on an agricultural land, with a permit up to 5 floors. Anas choose to take an apartment on the third floor because he was afraid of the laws and the risk of demolishing of the illegal floors. Anas says that the building condition is pretty good, it has an elevator, water, electricity, gas, and each apartment has its own electricity meter. The building is so different than the one for Anas’s family at Sayedda Zeinab, that follows “old rent” law and they pay monthly 40 EGP. According to Anas, his landlord is not suffering as he gets 30,000EGP per month as a total amount of rent of his building.

The Owners are Angry!

The majority of the landlords are in anger, they feel humiliated because of the low-values of rents they get, moreover, they feel that the law is unfair to them. Magdy Bedier, who works as an engineer, owns a building in the Niile Delta city of Mansoura. It has 12 residential units and two commercial ones. Originally, he was getting a rent of 25 EGP per unit, but in 1965, the law was changed to make the rent lower, which netted him 11 EGP instead.[7] The building has been declared unsafe, and the majority of the units now are vacant, while the land price is 62 million EGP ($3.5 million), but the remaining renters are fighting eviction.

Figure 2: An advocacy sticker for the “No to Old Rent law” group

Old Rent owners organized a number of demonstrations[8] to pressure the parliament to abolish the “old rent” law[9]. Their demands and slogans focus on the unfair situation they witness from the renters, and that the renters should leave the units.

One million families have left Old Rent units in the last ten years

Renters are leaving though, and in big numbers. We do not know where to though. Maybe some of them are dead or joined families who rent according to “new rent” laws, but mostly that the majority moved to informal neighborhoods. The last suggestion is the most affordable to those families, because those units in the slums are affordable with prices that have nothing to compare to “new rent” prices.

Consequences of Abolishing the law

We discussed many solutions with the renters and the owners. The renters were flexible and open to a range of solutions, while the owners were not, and they believed that there is no solution but to abolish the law, kick the renters out, so they could sell on or rebuild.

One of the renters’ suggestions, was to evaluate the building value, and decide a rent value that has an annual increasing percentage that would suit the rent amounts which was already paid over the years by the renters. This can be a fair solution, to have new rents that are affordable, suitable with the contemporary economic situation, and suitable to the money that was already paid over the years. Besides, many families since the 1970s paid already big amounts of key-money in order to get the units, some a considerable portion of the flat’s value then, which should be taken in consideration.

The hardest part in changing the law, is about how to it achieve justice to everyone, as families in the same buildings are not in the same financial status after all the socio-economic changes in the last 20 years. Bulaq Abulella, for example, is a popular neighborhood that includes many elders who live on pensions, many of whom are also widowed. They can never afford to pay any rent higher than the few Egyptian pounds in which they pay monthly. Their pensions can barely afford their everyday expenses and their medicine.

A way forward?

Under the contemporary circumstances, of commodifying the residential units, an absence of justice in housing prices—whether to rent or to buy, a high incidence of housing deprivation especially a lack of infrastructure, as well as the continuity of building collapses that are usually “old rent” buildings, the government must take the initiative to reach a just and fair solution to the issues of “old rent”, which it can only be responsible for. Solutions that address the entire housing spectrum, especially the rapidly inflating housing costs, and that address the inequities of the “new rent” law as well.

In that light, and before any steps are taken to liberalise Old Rent, the government should:

- Prepare a detailed socio-economic survey of Old Rent tenants, that takes into account geographical location, income, and the building conditions and age, should be completed.

- Prepare relocation models based on this survey that show the opportunities available for the different families to relocate, especially the poor, low-income, ageing and disabled. Accordingly, a comprehensive housing support program should be designed to allow the relocation of precarious Old Rent tenants to alternative adequate housing within a 2km radius of their current homes.

- For non-precarious Old Rent tenants, any liberalization of rents should happen on the medium to long term to allow them time to adjust to the new values, or relocate if need be according to their financial situation and the availability of units.

Acknowledgements

Written by: Omnia Khalil

Editor: Yahia Shawkat

Main image: A copy of an Old Rent Contract

Notes and References

[1] Legal facts related to Old Rent are based on the last iteration of the law, Law 49/1977 and its major amendment Law 136/1981, except where otherwise noted. Note: Many articles of these laws have been struck down in Constitutional court, therefore an official recent printed copy of the laws must be consulted.

[2]Law 4/1996 liberalised all new rental contracts (hence called New Rent), from rent control and to be governed by the Civil Code (Law 131/1948, arts 558 to 635).

[3] Masrawy, “3 Asbab Tu’atil Qanun Al-Igar Al-Qadim,” Masrawy, September 17, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/yavng7uu.

[4] Al-Youm al-Sabe’, “Nanshur Nass Mashrua’ Qanun Al-Igar Al-Qadim Ba’d Ihalatuh Ila Lagnit Al-Iskan Bil-Parlaman,” Al-Youm al-Sabe’, 05.01.2017 https://tinyurl.com/ycn2lbom.

[5] Since 1969, Law 62/1969 allowed bequeathal of rent contracts to first degree family members

[6] $1=17.7 EGP – June 2018.

[7] Before Law 49/1977 fixed rents to values determined by committees, a number of rent reduction laws were enacted, including Law 7/1965 (20% reduction for contracts between 1952 and 1962, and 35% for contracts from 1962)

[8] Al-Ahram, “Bil Sowar.. Mullak Al-’aqarat Al-Qadima Yatazaharum Amam Maspero Lil-Mutalaba Bi Tatbiq La-Shar’a Fi Qanun Al-Igarat,” Al-Ahram, November 16, 2012, http://gate.ahram.org.eg/News/272849.aspx.

[9] Al-Ahram, “Waqfa Ihtigagiyya Li-Mullak Al-’aqarat Al-Qadima Li Tamthilahum Fi Lagnat Ta’dil Qanun Al-Igar Al-Qadim,” Al-Ahram, September 26, 2012, http://gate.ahram.org.eg/News/254986.aspx.