- Published on 12 October 2022

At ten minutes past three in the afternoon, on October 12, 1992, a 5.6 magnitude earthquake struck northern Egypt. In less than a minute thousands of buildings collapsed or were heavily damaged. Their rubble and chaos claimed over 560 lives, where many of the dead included children who were trampled during stampedes in three schools in Cairo.

Thankfully, 12,000 people were lucky to escape from under the stones and concrete, however injured. Even though they escaped with their lives, those lives would be forever transformed by the Earthquake. The tremors that followed claimed more buildings, making over 120,000 people homeless in seven cities across central Egypt, and many more villages.

At first temporary camps were organised, some of which used the shells of decommissioned public buses as shelter. Between the coming few weeks, and eventually months, thousands of families were relocated to housing in a number of Masakin al-Zilzal (Earthquake Housing) estates, the more famous of them in the Moqattam district of Cairo, while the rest were in so-called New Cities outside of the capital. Other buildings were repaired, while some chose to keep living in their decaying homes, unsure or unable to live in new, remote estates.

Many geological studies have been written about the earthquake,[1] as well as some that describe the event,[2] but less so the sociological and urban implications.[3] This has left a large gap in understanding the largest urban disaster to hit Egypt in the 20th Century, forcing more people to be displaced than any other peace time event, including the building of the Aswan high dam.

To commemorate the 30th anniversary of the 1992 Egypt Earthquake, the Built Environment Observatory is preparing a special series by a number of authors to try and fill some of this gap over the coming months, through mapping, oral accounts, and archival research. On this occasion, we would also like to invite anyone who has firsthand accounts, or material on the earthquake to share it with us, especially if that is outside of Cairo, or in rural areas.

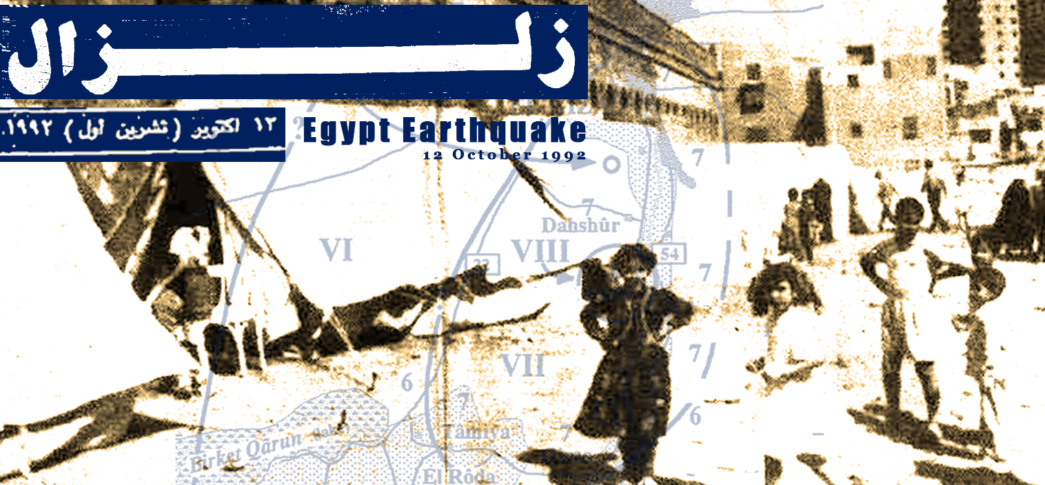

Main Image

Original photograph: Emergency tents by the Ibn Tulun Mosque, Sayida Zeinab, Cairo. William Morcos, Al-Jumhuriya, 19 December, 1992.

Notes & References

[1] H. M. Hussein, “Source Process of the October 12, 1992 Cairo Earthquake,” Annals of Geophysics 42, no. 4 (November 25, 1999); Attia El-Sayed, Ronald Arvidsson, and Ota Kulhánek, “The 1992 Cairo Earthquake: A Case Study of a Small Destructive Event,” Journal of Seismology 2, no. 4 (December 1, 1998): 293–302; M.M. Soliman, “The Dahshour (Egypt) Earthquake of 12th of October 1992,” International Conferences on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics 14 (April 4, 1995).

[2] Galila El Kadi, “Le tremblement de terre en Égypte,” Égypte/Monde arabe, no. 14 (June 30, 1993): 163–96; Martin Degg, “The 1992 ‘Cairo Earthquake’: Cause, Effect and Response,” Disasters 17, no. 3 (1993): 226–38.

[3] Benedict Florin, “Banished By the Quake Urban Cairenes Displaced From the Historic Center to the Desert Periphery,” in Cairo Contested: Governance, Urban Space, and Global Modernity, ed. Diane Singerman (American University in Cairo Press, 2009);

محمد نصر فريد, “تحليل بعض مشكلات مجتمع متضرري الزلزال بمدينة النهضة – حي السلام” (معهد التخطيط القومي: معهد التخطيط القومي, March 1995).