- Published on 28 May 2018

As part of the Egypt State of Housing 2017 Series, this report analyses the “Million Unit” Social Housing Project (SHP), the main subsidised housing project that was launched in 2011, with the aim to build one million housing units over five years, and is still active today. So, what has it achieved?

To read other articles in the State of Housing 2017 Series, click here

1. Briefly, what is the SHP?

The SHP follows in a long line of supply-side subsidised housing projects that stretch back to the 1950s. As its forebears, it provides a singular housing solution; ready built and finished housing units in multi-story blocks, located in remote locations. Other than a very limited number of rental units, the majority are sold to beneficiaries, mostly through state-subsidised (below-market rate) mortgages.

In early February, 2011, the then Minister of housing, Mohamed Fathy al-Baradie, announced a new project to build one million housing units for low income families,[1] as a successor to the Mubarak National Housing Project (NHP), days before its patron was removed in a popular uprising. A front-page ad appeared two weeks later in local newspapers opening registration for the units (Figure 1). Within a year, over five million people had applied.[2]

Figure 1: The first SHP ad as it appeared on 21st for February 2011 on the bottom right hand corner of the leading official daily, Al-Ahram

The first units started to be built in FY 2011/2012 with promises of delivery within a year. However, political turmoil after the January 2011 Revolution and with various changes in government, the SHP was relaunched in May 2014 when a fresh call for applicants was made giving much more detail about prices, locations and conditions (Figure 2). While at first there was priority for the previous 5.5 million applicants, that priority was later removed, and previous applicants had to reapply.

Figure 2: First detailed ad for the SHP as it appeared at the bottom half of the front page of the lead official daily Al-Ahram on 19.05.2014

The Ministry of Housing, Utilities, and Urban Communities (MoH), is the main government entity responsible for the SHP, with a number of affiliated agencies responsible for different aspects of the project. The main management vehicle is the Social Housing Fund (SHF), which coordinates funding and implementation. The Guarantee and Subsidy Fund (GSF), receives and vets applications, and allocates units and subsidies to the accepted, as well as coordinates mortgages allocated through the banks. It is due to be merged with the SHF, which is still under formation, sometime this year. The New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA), is the largest land developer in Egypt, and builds units in the so-called New Cities under its jurisdiction, using its own funds, which are then settled with the SHF. The Central Agency for Construction (CAC), and the local governorates’ Housing Departments build units in the cities, towns and villages under local administration with funds allocated to them by the SHF. The Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) supplies below market-rate credit to banks under the Low-income Mortgage Initiative (LMI), to disburse to applicants based on criteria it set with the GSF.

2. Who is the SHP for?

The SHP has been billed as a programme for the loosely defined “low-income” households, where it offers housing across the income spectrum. There is only one option of ready-built and finished apartment units, that are mostly sold, in addition to a very limited number of rental units (Table 1). Of the ownership schemes, the standard SHP Subsidised scheme is the mainstay sub-scheme, covering almost two thirds of units offered this year. It has set income bands for people to qualify for a subsidised mortgage according to the CBE’s LMI (Table 2), and an income-inverse cash subsidy towards the cost of the unit (see below). There are exceptions for maximum income for families of police and army personnel injured or killed on duty.[3] The two other ownership sub-schemes have no income restrictions, and no cash subsidies. The Unsubsidised SHP sells units at cost, or with a small profit margin, and in its latest iteration has been offered exclusively to Egyptians abroad, stipulating payment in US dollars. The Premium SHP (al-iskan al-igtimae’y al-mutamayiz), also called Sakan Misr, is considerably more expensive, being sold for profit, but still falls in the LMI’s subsidised mortgage scheme if applicants meet the bank’s requirements.

Table 1: SHP Schemes

| A – Ownership | ||||||

| Sub-programme | HH Income Bands (EGP/mth) | Cost (EGP) | Cash Subsidy (EGP) | Payment Scheme | Units Offered for

Reservation in FY17/18 |

|

| A1 Subsidised SHP (90m2) | Min 1500 – max 4750 | 184,000 | 0 – 25,000 | 16-40% down-payment + 20yr subsidised mortgage at 5-7% | 125,000 | 68% |

| A2 Unsubsidised SHP (75-95m2) | None | 165,000 -250,000 | None | Cash or 25% down-payment + 3yr yearly instalments | 18,061 | 10% |

| A3 Premium SHP/ Sakan Misr (115m2) | None | 425,000-575,000 | None | Cash, 20% down-payment + 5yr quarterly instalments, or 20yr subsidised mortgage at 8-10.5% | 40,000 | 22% |

| B – Rent | ||||||

| Rental SHP

2-bedroom (75m2) |

Min 1000 – Max 1450 | 300/mth + 7%/yr | Imbedded | 1000 EGP deposit + 3000 utilities’ hook-up | 0 | 0% |

| Rental SHP

3-bedroom (90m2) |

Min 1000 – Max 1450 | 410/mth + 7%/yr | Imbedded | 1500 EGP deposit + 3000 utilities’ hook-up | ||

| Total | 183,061 | 100% | ||||

| Sources:

Rental SHP Ad 07.09.2016 http://www.newcities.gov.eg/dispNews.aspx?ID=2534 Unsubsidised SHP Ad 02.11.2016 http://newcities.gov.eg/dispNews.aspx?ID=2679 Subsidised SHP 9th Ad 24.07.2017 http://www.newcities.gov.eg/dis_alaan.aspx?ID=85 Egyptians Abroad SHP Ad. 18.01.2018 http://www.newcities.gov.eg/dis_alaan.aspx?ID=167 Egyptians Abroad SHP website http://www.social.nuca.gov.eg/ar/Home.aspx NUCA Sakan Misr ToR 10.2017 |

||||||

The Rental SHP scheme was newly introduced in 2016, with a plan to make up 12% of the programme,[4] as well as an even smaller component of rental cash assistance. But only 5700 units have been offered since then, while the GSF may not repeat it.[5] The rental units target poorer households whose incomes were lower than the mortgage scheme allowed, but lists as a priority households whose neighbourhoods have been slated for slum clearance.[6] The units’ rent ranges between an acceptable 21% of income, to a high of 41% depending on unit size and income level (Table 1). Contracts have an initial duration of seven years, after which the beneficiaries’ household income will be re-evaluated to either re-evaluate the rental value, or, offer a right-to-buy scheme through mortgage, with the amount of rent paid deducted from the price, if their income qualifies them for one, or to pay the whole price in cash.[7]

Table 2: Central Bank Mortgage Initiative regulations by unit price and income bracket

| Income Bracket | Max. Monthly HH Income EGP | Rate | Max. Unit Price EGP |

| Upper Middle Income | 20,000 | 10.5% | 950,000 |

| Middle Income | 14,000 | 8.0% | 700,000 |

| Low Income 2 | 4750* | 7.0% | 184,000** |

| Low Income 1 | <2100 | 5.0% | |

| Source: CBE “Circular Modifying Mortgage Initiative for Low and Middle-income”, 22.07.2017 https://tinyurl.com/y8qamla2

*Defined by SHF/GSF. **Defined by SHF/GSF. Figures from most recent 9th SHP ad, 24.07.2017 |

|||

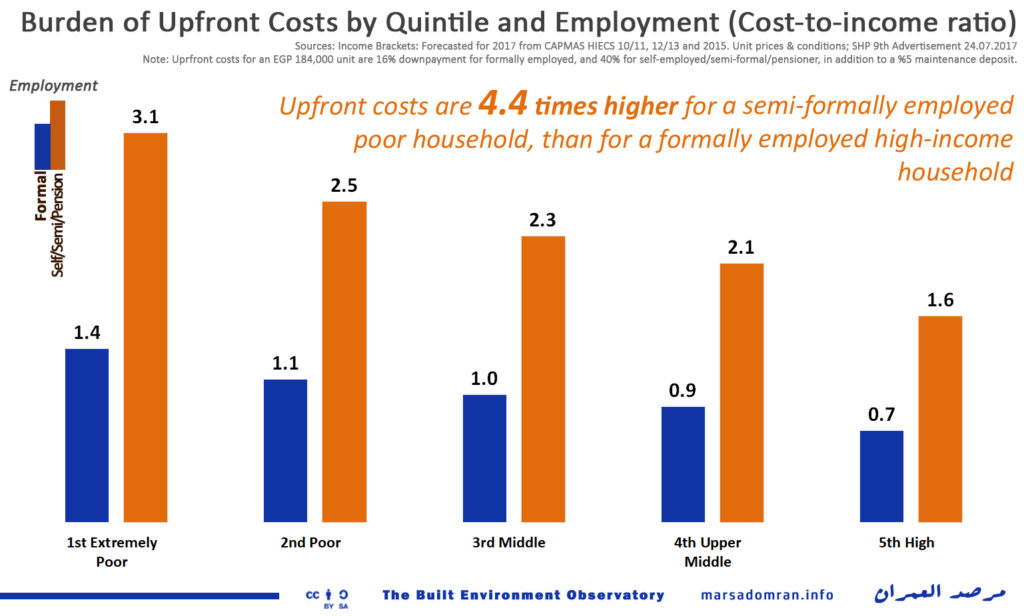

Focusing on the standard Subsidised SHP scheme, which has the widest reach, we find access for the precarious and/or poor households largely theoretical. On one hand, the mortgage scheme favours formal private sector or government employees, over the self-employed, the semi-formally employed, and pensioners. The latter are required to pay more than twice the down-payment that formal employees pay, while total up-front costs for the poorest of them reach three times their annual income, compared to only 1.4 for the formally employed (Figure 3). This of course negates much of the accessibility of a mortgage in the first place and is reflected in how only 5% of units over the first three years of the project has been allocated to those not formally employed, only rising to 19% over the current FY 17/18 after changing some of the requirements,[8] even though they constitute two thirds of the workforce.[9] Even if they could pay the large down-payments, those who are not regular employees with a set monthly salary, rely on seasonal income, that would not suit the monthly mortgage payments, even if they could cover them annually.

For the formally employed, the SHP also discriminates against poorer households, where the lowest quintile pays upfront costs that are double those for the top income quintile, even after receiving a higher cash subsidy (Figure 3). This forces many to borrow, mostly informally, from employers, family or rotating saving schemes, to afford the high down-payments.[10] In addition to the mortgage, this borrowing increases the debt burden that will need to be repaid, adding considerably to housing-related costs for the most vulnerable beneficiaries.

With the rental scheme making up less than 3% of the SHP so far, and may not be repeated, poor and vulnerable households are either burdened by, or excluded from the SHP, much as they were at the beginning of the project.[11]

At the other end of the scale, higher income households who breach the SHP’s already high upper limit on income, may “raid” SHP units, as income declarations rely solely on declared income, and not on actual income, which may come from trade, remittances, and/or the rent or sale of property.[12]

Figure 3

3. Is the SHP demand-based?

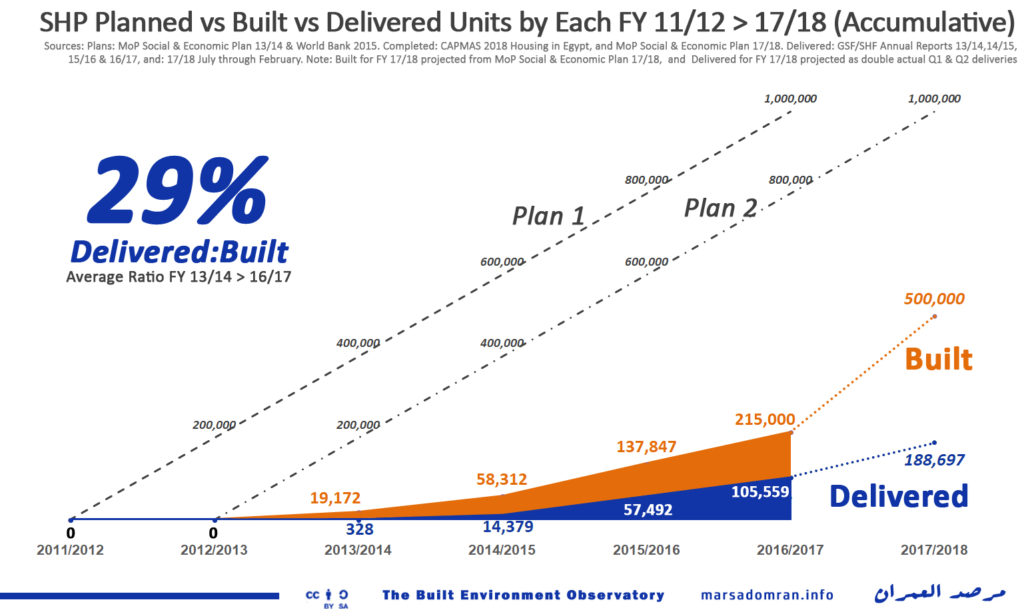

The SHP plans set goals of building one million units, first between FYs 11/12 – 16/17, and then pushed to 17/18. There has never been an explanation for the target number, and between the first ad in 2011 and the end of FY 2016/2017, only 215,000 units were completed, while by the end of this year that number is supposed to reach 500,000 units (Figure 4). This would be exactly half the targeted one million units that should have been completed by then.

More importantly, the social gain of these half a million units will have been miniscule compared to the investments, as less than 190,000 units would have been delivered to beneficiaries by the end of this year, translating to an average rate of about 37,000 units per year, with a very low average delivered-to-built ratio of 29% over the last five years (Figure 4).[13]

Figure 4

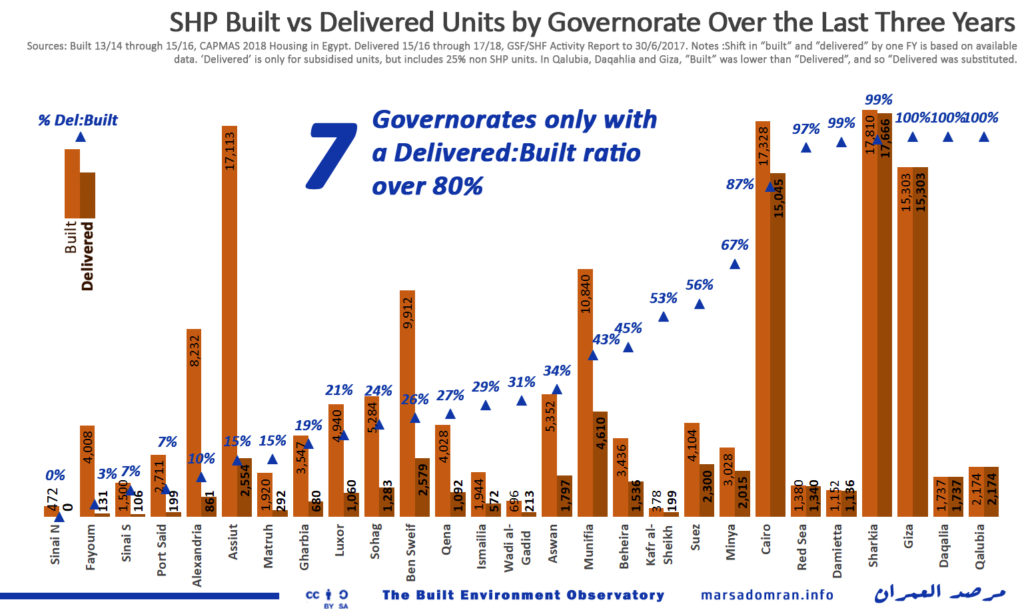

Looking at this in more detail, SHP units have been built in all 27 governorates, and even after adding a grace period of one year between when units were completed and delivered (due to discrepancy in the data), in 20 governorates, less than 80% of the units have been delivered to applicants, with the delivery rate lower than 50% in 17 governorates, and zero in North Sinai (Figure 5).[14] This extremely low delivery rate can be explained by two main factors.

Figure 5

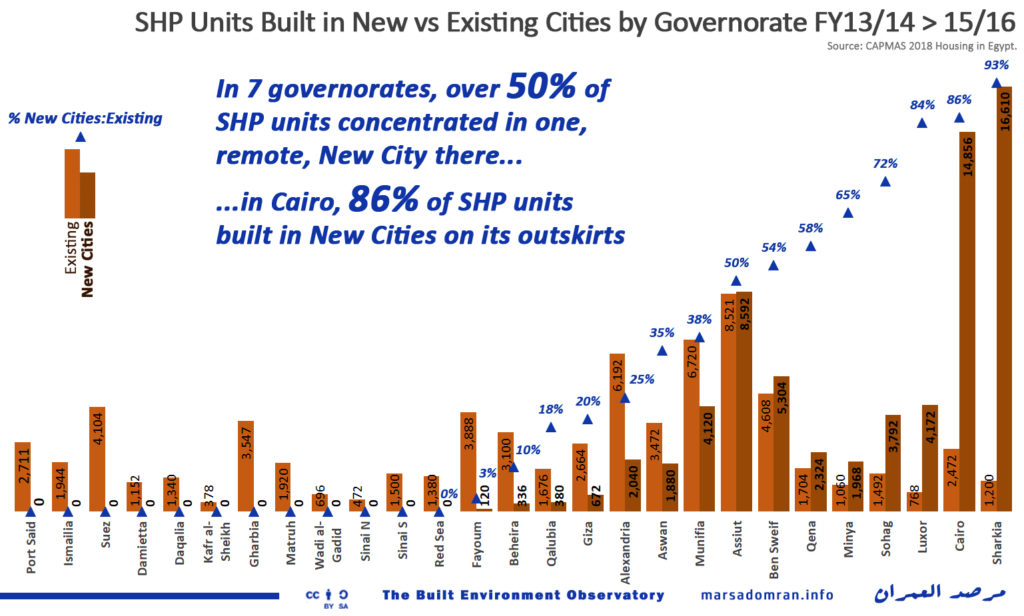

On one hand, thousands of units have been built with no demand studies for whether low-income households would want, or could afford relatively expensive three-bedroom apartments in housing blocks. While in others, units did not meet demand, causing exemptions, or delays in delivery. Over half of Egypt is rural, and most households there prefer family houses, over apartment blocks. It has also not helped that in seven, mostly provincial governorates, over half the units were concentrated in a single New City each, usually a suburb of the provincial capital (Figure 6). This means that they are only suitable for those already living in the capital, and simply ignore the rest of those living in other towns and villages.

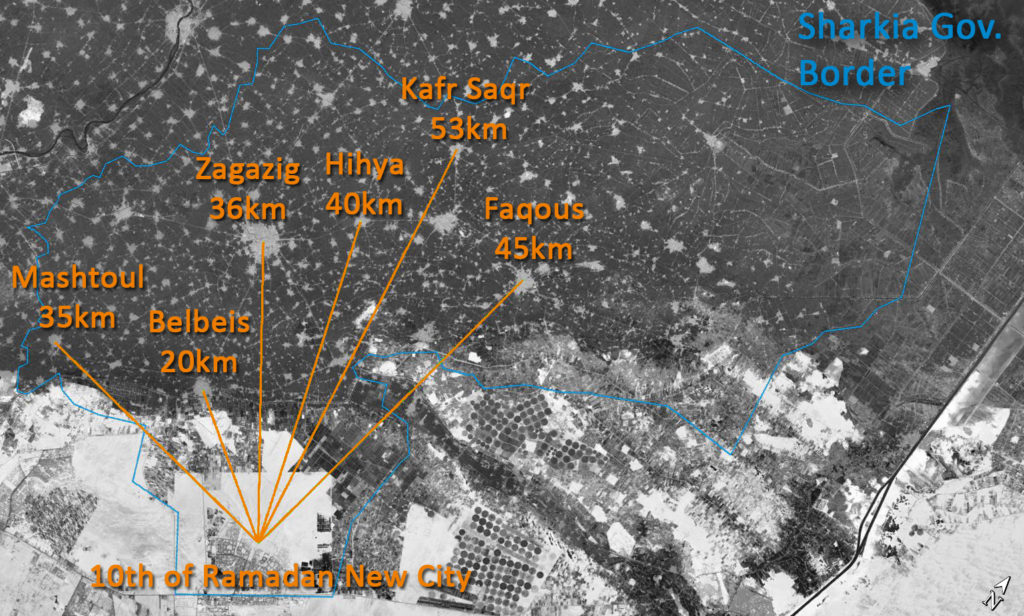

With a large unsold inventory of built units, the Ministry of Housing has taken a number of extraordinary actions to sell them. One move has been to require applicants in towns where housing was unavailable, to change to New Cities that were 20 to 55km from where their original choices were (Figure 7).[15] Those in the Baharia Oasis, were instructed to change their application to 6th of October New City, over 300km away. Otherwise applicants could withdraw their applications. Another move has been to sell SHP units to higher earning applicants, basically upper middle-income earners by introducing non-cash susbsidised sub-schemes such as the “Non-subsidised” or “Liberal” SHP ads,[16] Prime Social Housing/Sakan Misr, and the Egyptians’ Abroad schemes. A third move has been to sell units in bulk to local government, that would use its own local mechanism to sell the units on to applicants.[17] Most probably higher income households, as poorer households did not, or could not apply when they were initially advertised.

There was also no participation in the design of the SHP units, which followed a terms of reference document that the MoH released in 2011 as part of a competition to design the new units. The document did not stipulate any measure of citizen engagement or the participation of potential applicants, nor the evaluation of previous housing projects.[18] The ToR merely directed the designers to “design housing units that are appropriate to the social and economic needs of the Egyptian family in the different regions and areas across the nation”.[19] In the end, the winning design produced just one design option for the entire nation; a series of housing blocks of two and three-bedroom units,[20] ignoring local preferences of extended-family dwellings, or small serviced plots for self-build.[21]

Figure 6

The other factor is the complicated, and unsuitable mortgage scheme. This has resulted in a very slow process for the SHF/GSF, as well as the banks supplying the mortgages, in delivering the units, leading to complaints of delayed delivery.[22] About a quarter of applicants were refused mortgages from the banks because of other debts,[23] while half of applicants in the latest round which used a new online system, were found to have entered erroneous details and required re-entering.[24] Up to 50% of applicants in the first three stages were surprised to find that they were required to pay an additional amount to the initial down payment of EGP 5000,[25] sometimes reaching ten times that amount or more, leading many to either defer delivery of the unit, or to cancel their registration and withdraw from the project. Indeed, a number of applicants have had to resort to borrowing informally,[26] or to asking relatives for money.

This lack of available information has resulted in the SHP call centre receiving 3000 calls a day, where callers expressed many misconceptions of the project, leading a portion to reserve units because they don’t know when the next time units will be made available in their location.[27] This was well before a further 500,000 units were advertised in mid 2016.

Figure 7: Distances as-the-crow-flies between existing towns and the 10th of Ramadan New City in Sharkia Governorate. Base image courtesy of Google Earth

4. Is the SHP needs-based?

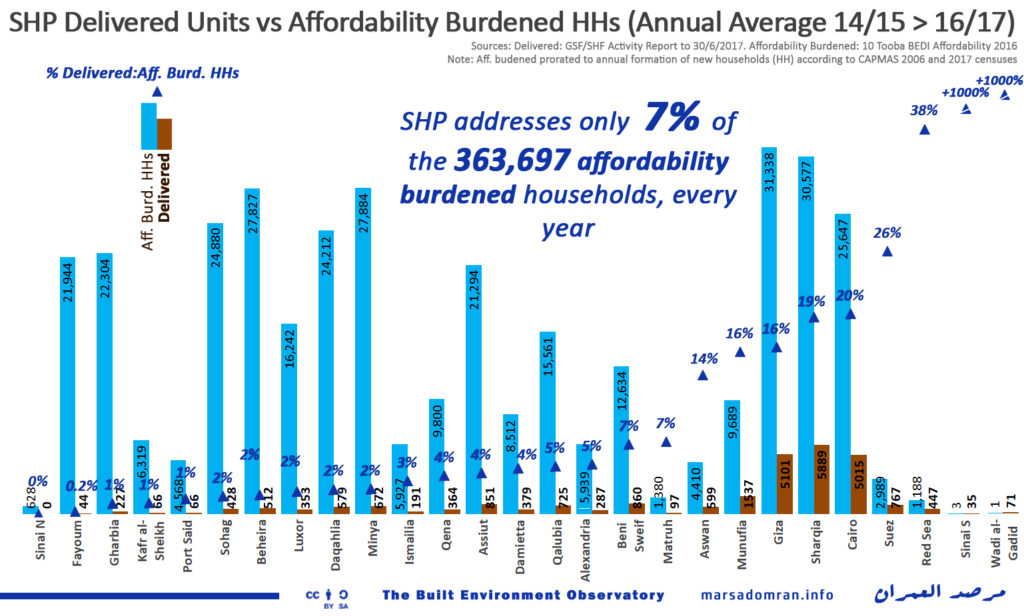

If the SHP wasn’t designed according to market demand, as a social project it could have been designed to respond to social needs, targeted at places with a high housing affordability burden. However, when we compare the number of delivered units to newly formed households that cannot afford housing, we find the SHP is only able to address 7% of those on average (Figure 8). In 16 governorates 5% or less have been served, while in South Sinai and Wadi al-Gadid, there was over-delivery.

Figure 8

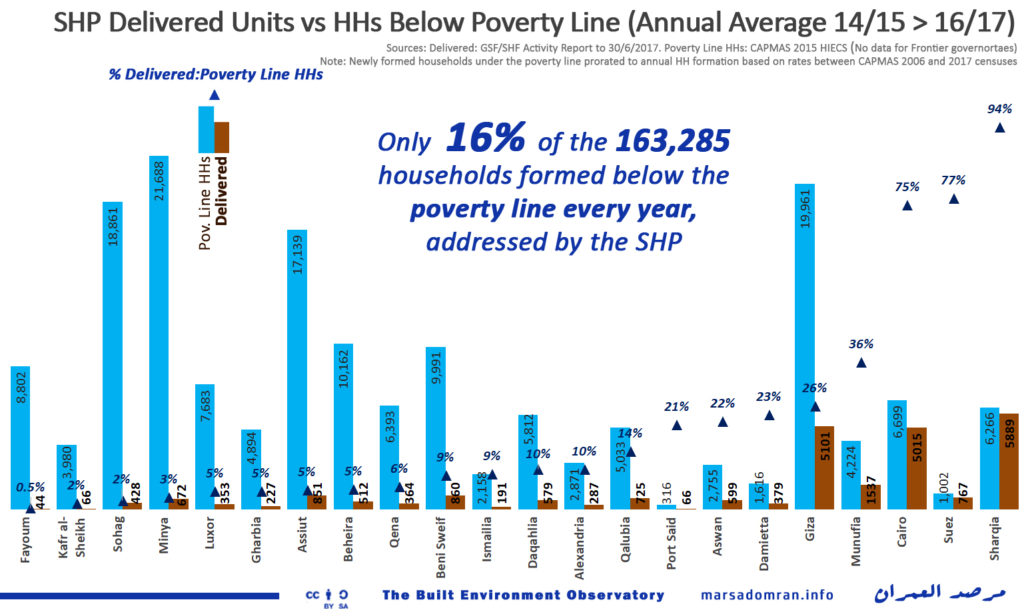

Even focusing only on the 160,000 households formed every year below the poverty line, the SHP only manged to serve 16% of those, and as stated before, only theoretically. The better served governorates were Cairo, Suez, and Sharqia, with a coverage of 75% or over. However, in Upper Egypt, which has a high concentration of poverty, 7 out of 8 governorates there had coverage of 10% or less.

Figure 9

5. How much has the SHP cost?

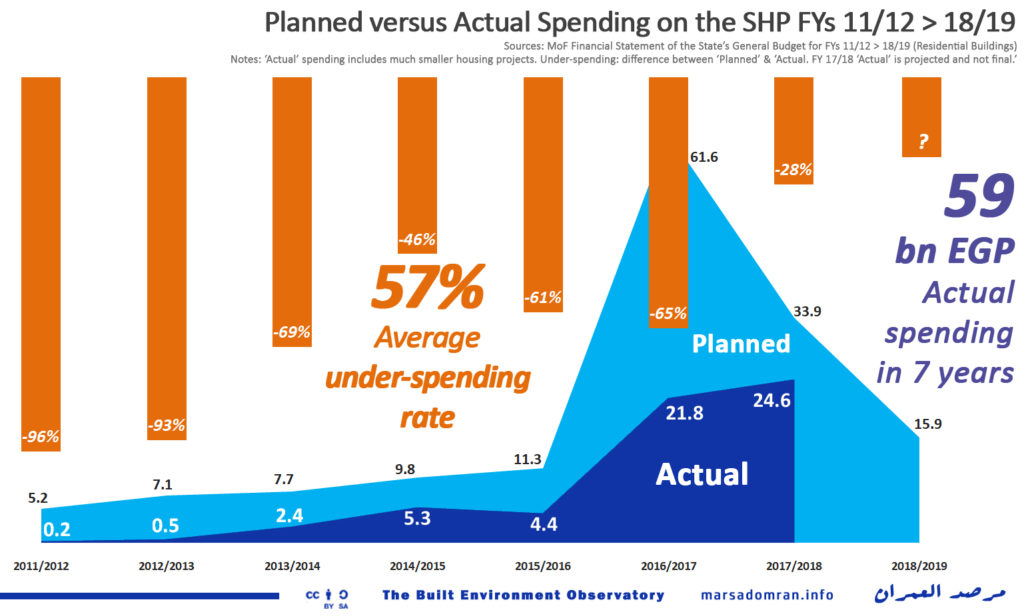

Over the last seven FYs, the SHP has been pledged EGP 136.5bn. However, less than half of that has been spent, with an average under-spending rate of 57%, as actual spending averaged EGP 8.3bn per year, or about EGP 92 per capita (Figure 10). For a social project, aiming to fulfil constitutional and international adequate housing goals, this gross underspending needs to be confronted. Underspending by over 5% is a sign of weak planning for the SHP, that could indicate any number of shortcomings including lack of capacity, complicated management, diversion of funds to other projects, and lack of demand.[28] It is the last two that are most pertinent as far less underspending has happened in overall public investments,[29] while the SHP is dependent more on revenue from unit sales, than on public money.

Figure 10

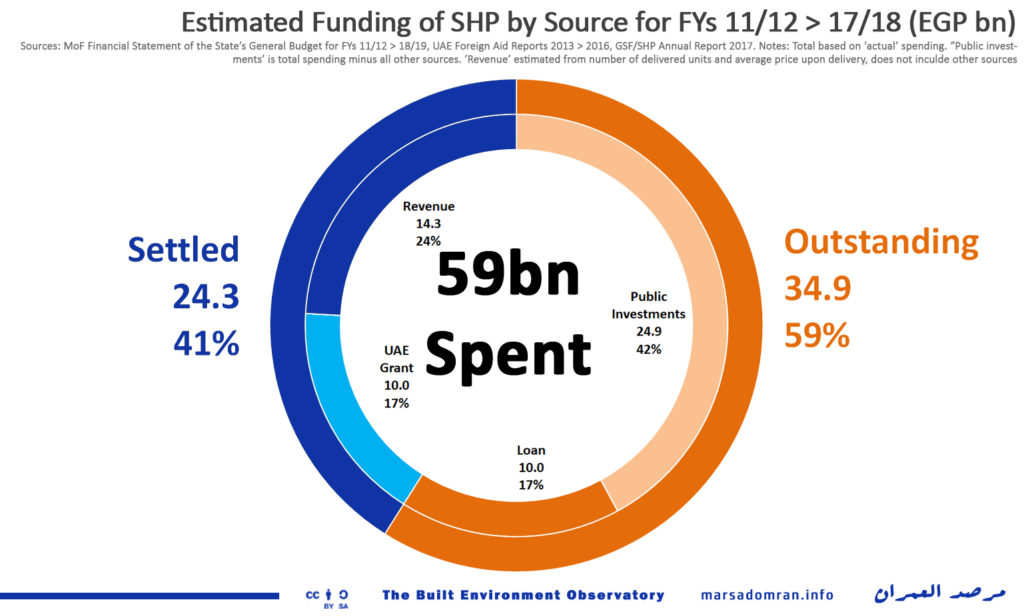

Taking a closer look at the SHP’s finances, we can estimate that direct government funds have constituted about two fifths of the total cost of the SHP so far (Figure 11).[30] The balance has been funded by revenue from unit sales (24%),[31] an international grant (17%),[32] and a loan (17%).[33] Government ‘investments’, along with the loan constitute the ‘outstanding’ 59% of spending, and should be paid back from the revenue generated over the course of the project. This mix of sources, especially the slow revenue from sales, goes some way to explaining the erratic spending on the project.

Figure 11

6. How much subsidy has been assigned to the SHP?

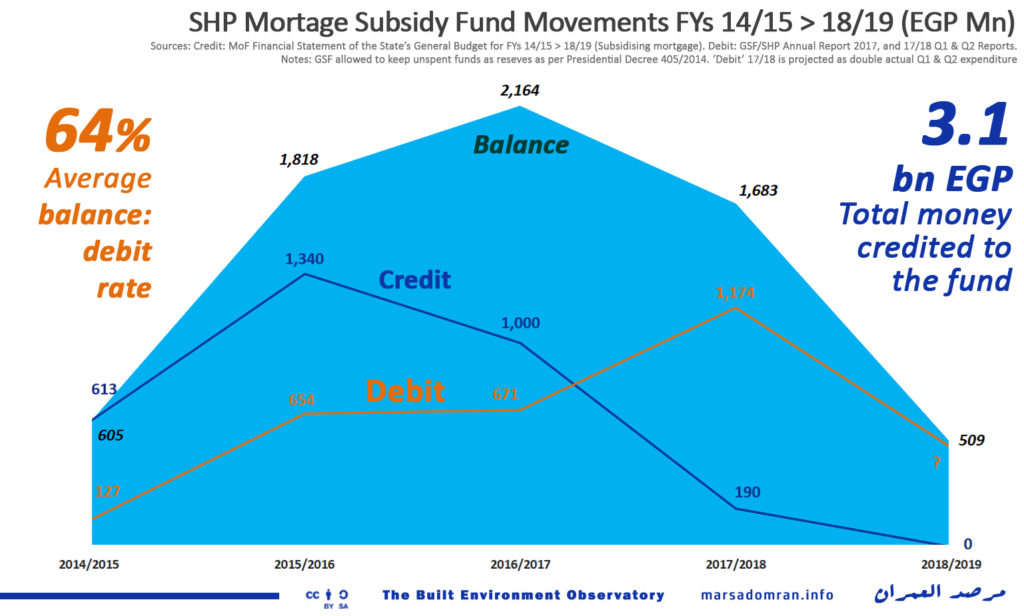

Since FY 2013/2014, EGP 3.1bn has been credited to the GSF, to disburse as cash subsidies upon purchase of an SHP unit (Figure 12). But disbursements were quite low in the first four years compared to the funds available, mirroring the slow delivery of SHP units to applicants. This has led to a big drop in credit towards the GSF, where in the next FY it will receive zero extra funding. It would also mean that there will be a considerable drop in the number of subsidised units delivered in FY 2018/2019 to around 30,000, or about half the current FY,[34] despite more units on track to being completed.

Figure 12

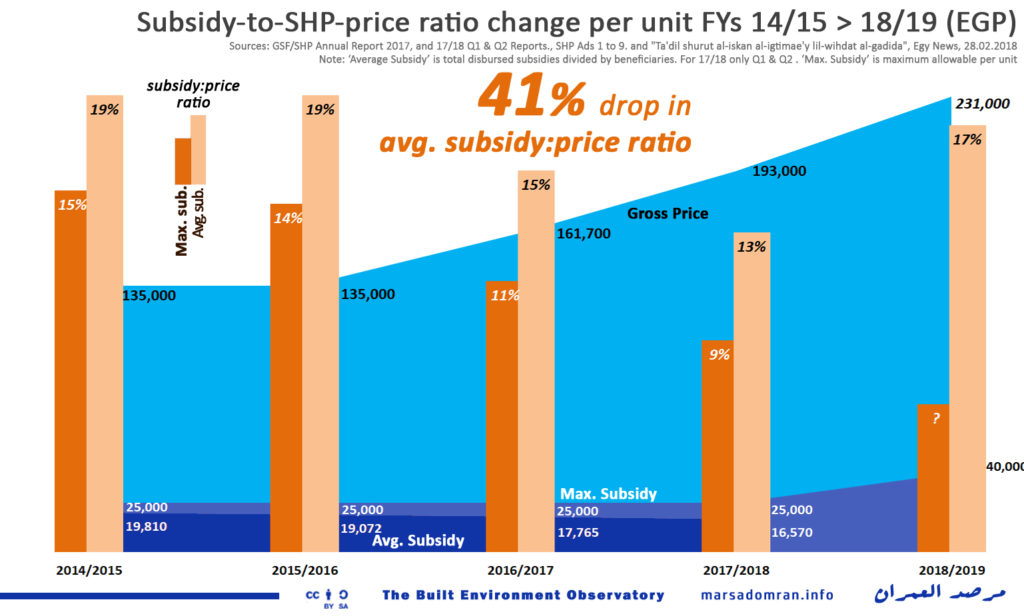

On a related note, the average subsidy-to-unit ratio has fallen by an incredible 41% since the start of the programme, as the average disbursed subsidy per unit fell by 16%, while prices rose by 43% in FY 17/18, and are due to rise to 71% in FY 18/19 (Figure 13). That is despite increased funds for subsidies through a new $500mn World Bank loan supporting the GSF subsidy component, and 40% of it being disbursed since 2015.[35] The overall proportion of non-subsidised SHP units has fluctuated between 17% and 81% of units, with an average of 73% over five years (Table 3).

Figure 13

Table 3: Delivered GSF Units by type

| Delivered | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 Projected | TOTAL | |

| SHP Units | Total | 328 | 14,051 | 43,113 | 48,067 | 83,138 | 188,697 |

| Subsidised | 0 | 2,426 | 30,141 | 37,004 | 67,598 | 137,169 | |

| Sub: Total | 0% | 17% | 70% | 77% | 81% | 73% | |

| All GSF Units | Total | 3,420 | 18,793 | 45,067 | 48,674 | 83,820 | 199,774 |

| Subsidised | 0 | 6,423 | 34,272 | 37,785 | 70,824 | 149,304 | |

| Sub: Total | 0% | 34% | 76% | 78% | 84% | 75% | |

| Sources: GSF/SHF Annual Report up to 30/06/2017, and: 17/18 Q1 & Q2 reports

Note: Delivered for FY 17/18 projected as double first half of the FY |

|||||||

An implicit subsidy,[36] that does not show on the GSF accounts, has been added to the SHP through other items of the general budget. EGP 2bn was paid out under “Social Housing Subsidy” in FY 15/16,[37] while a further EGP 1.5bn was planned for FY 16/17, but was never paid out.[38] This budget item was renamed “Low-income Housing Subsidy” for FYs 16/17 through 18/19, with zero funds. Though, under “Other Items”, EGP 3bn has been promised to the SHP in FY 18/19 as per an explanation in the budget document.[39] This latter subsidy is part of NUCA’s pledge to cover differences between the advertised cost of EGP 154,000, and the actual cost incurred after the devaluation of the Egyptian pound in November 2016, of EGP 180,000, for 190,000 units from the 8th SHP ad.[40] If it is reassigned as an explicit subsidy, it will only bring the subsidy-to-price ratio up to pre devaluation levels, which is only fair. However, this applies only for applicants of the 8th ad, and not for the 9th ad, which have applied to more expensive units at the same subsidy regime, thereby with a far reduced subsidy-to-price ratio.

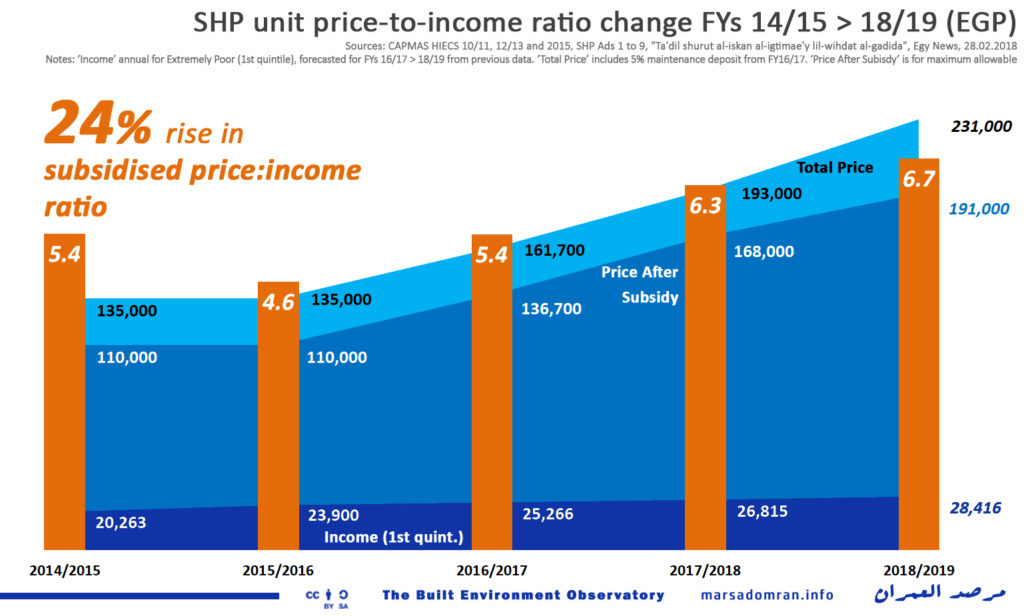

This ambiguous subsidy regime, especially with subsidy items in the general budget showing as “zero”, has forced the government to issue a formal statement denying “rumours” that housing subsidies have been cut,[41] after news outlets reported what was in the budget tables. More importantly, the SHP lacks a dynamic subsidy regime, as well as design and implementation considerations, that are able to make the SHP affordable to the poor. Unit costs have risen exponentially, while incomes have not. By the next FY, even after applying the maximum allowable subsidy, SHP units will still be 24% less affordable than they were in FY 14/15 for Extremely Poor households in the lowest quintile, the SHP’s supposed main target beneficiaries (Figure 14).

Figure 14

7. What should be done to improve the SHP?

Where one assumes the primary role of social housing programmes is to address those households living in inadequate housing, the SHP ignores millions of Egyptian households’ housing needs, in its bid to implement supply-based mortgage financed ready-built housing. The SHP’s limitation is starkly expressed in how its singular component has only managed to address the needs of 16% of new households annually formed below the poverty line, and 7% of those who cannot afford housing. While the fact that it is sold, rather than rented, has meant that many people view it as a commodity where a number of units stand empty, or, or illegally sold or rented out.

Out of six components that make up deprivation in the built environment in Egypt;[42] secure tenure, burden of housing costs, crowding, non-durable shelter, lack of sanitation, and lack of water, only crowding, and non-durable shelter, may require housing to be replaced. And with a high vacancy rate of 11.5 million units,[43] half of which are easily usable, all depravation could be addressed without building new units.

At a time when the government is amending the Social Housing Law 33/2014, and working towards its commitment to the constitution (Art 78), the Egypt Sustainable Development Strategy 2030 (Urban Development Pillar), the UN Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 11), as well as the New Urban Agenda, with the resources already available, there is opportunity that the SHP can be transformed in to a true social housing programme, one that addresses the array of low-income housing needs, and meets the national and international goals.

Towards that end, the following recommendations build and expand on the progressive restructuring of the SHP already proposed by the MoH’s new Egypt Housing Strategy that is currently being finalised (mainly components 10 – 14):[44]

A. Exclusive Focus on Affordability Burdened

- Income brackets should be restructured to address all families not able to afford market housing, based on local sub-national data, with a special focus on the extremely poor

- Income measurements should take seasonal variance into consideration, as well as the variances of precarious employment (informal, pensioned, artisanal self-employment)

B. Needs-based Support

- SHP should address the range of housing needs based on sub-national participatory needs assessments, that address regional and spatial differences, and cease all housing construction activity.

- Preliminary information from the BEDI shows needs within the SHP scope that can be addressed by soft measures such as; cash subsidy for difference between market rent and affordable limit (see brief below), grants/subsidised loans for building repair, and, subsidised loans for buying market units (existing LMI). These are;

- Affordability burden

- Easement of crowding

- Non-durable housing

- Preliminary information shows needs outside of the current SHP scope, but that can be managed by the SHF and implemented by other agencies through infrastructure and tenure recognition programs as:

- Informal tenure

- Access to sanitation and water

C. Central Management, Decentralised Execution

- SHF coordinates SHP, sets guidelines, and oversees execution of core components through:

- Local governorate Social Affairs Departments (after building capacity for rental cash support, and grants for home repair)

- Commercial banks (subsidised mortgage support for private and public sector units)

- Recurring funding for the SHP by taxing NUCA revenue by 20% should easily cover the restructured programme (Instead of the inconsistent surplus mechanism currently in place).

D. Rental Subsidy Programme Brief

SHF would receive and vet applications from both prospective tenants, as well as private or public landlords willing to participate in the programme. Detailed sub-national income and house price data (linked to property tax database), would establish affordability limits for tenants, as well as fair rental values for participating landlords, where the SHF database would match tenants to units, and calculate subsidy on a case by case basis.

Advantages for tenants:

- Affordable rent for five years (subsidised difference of market rent), reassessed after that, and tenant may be transferred to another participating unit if landlord does not wish to continue.

- Takes seasonal income into consideration (Affordable rent transferred to SHF on monthly, quarterly, or half-yearly basis, as agreed)

- Security of tenure (Registered contracts, premature end of contract upon agreement of both parties, tenant can request reassignment to other unit in another location in case personal circumstances change)

- Guarantee against eviction in case of late/non-payment for three months, after which income and affordability is reassessed

- Dispute resolution in case of misuse as first resort before courts

Advantages for landlords:

- Guaranteed income for five years based on pre-agreed values and annual increase, with no risk of late/non-payment (Regular SHF bank transfer)

- Rent is income-tax exempt

- Dispute resolution in case of misuse as first resort before courts

- Security of tenure (Registered contracts, eviction of non-complying tenants by SHF in case of failed dispute resolution, reassignment of tenant to another unit in case of force majeure for landlord to opt out, premature end of contract upon agreement of both parties)

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to David Sims, housing and urban expert, and Salma Yousry, UN-Habitat Housing and Urban Development Officer, for reviewing a draft of this report.

Written by: Yahia Shawkat

Main Image: SHP blocks near Ezbet Kamal, Fayoum, 2018. Courtesy of Google Earth

Abbreviations and Acronyms

| CAC | Central Agency for Construction (Affiliated to MoH) |

| CBE | Central Bank of Egypt |

| FY | Financial Year |

| GSF | Guarantee and Subsidy Fund (Affiliated to MoH) |

| LMI | Low-income Mortgage Initiative |

| MoH | Ministry of Housing, Utilities, and Urban Communities |

| MoP | Ministry of Planning, Monitoring and Administrative Reform |

| MoF | Ministry of Finance |

| NUCA | New Urban Communities Authority (Affiliated to MoH) |

| SHP | Social Housing Project |

| SHF | Social Housing Fund (Affiliated to MoH) |

| WB | World Bank |

Notes & References

[1] Al-Ahram al-Masaey, “Mashru’a Gadid Li Bina’ Million Wehda,” Al-Ahram Al-Masaey, February 4, 2018, https://www.masress.com/ahrammassai/27120.

[2] “Taqadam laha 5.5 Million Muwatin.. al-Iskan Tatarah 35 Alf Wehda Sakaneya Gadida fi 19 Muhafza”, Al-Ahram, 01.04.2013 http://www.ahram.org.eg/NewsQ/201991.aspx

[3] CBE “Circular Raising Mortgage Initiative Funds”, 08.10.2017 https://tinyurl.com/ycwk97f4

[4] World Bank, “Inclusive Housing Finance Program-for-Results Project – Project Appraisal Document” (Washington D.C., April 2015), p12 & 61 http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/319851468023373777/pdf/957910PAD0P15000100OUO090Box391428B.pdf

[5] Al-Bawaba News, “Raies sanduq al-tamwil al-’aqari tatahadath lil-Bawaba News,” Al-Bawaba News, February 14, 2018, http://www.albawabhnews.com/2945660.

[6] SHP Rental Ad 07.09.2016 http://www.newcities.gov.eg/dispNews.aspx?ID=2534

[7] “Shurut al-Iskan lil-Husul ‘ala Wehda bil-Igar”, Al-Borsa News, 11.08.2016, http://tinyurl.com/ze5llv9

[8] GSF/SHF, “Report on the Activities of the GSF and the SHF Until 30/6/2017”, p20 and: FY 2017/2018 Q1 (p14), Q2 (p13), and Q3 (p8) reports https://tinyurl.com/ycmzr389

[9] Ministry of Planning, “National Council for Wages, internal report” (Cairo: MoP, 17.09.2013)

[10] Salma Shukrallah and Yahia Shawkat, “Analysis: Government Policy Commodifies Housing,” Built Environment Observatory, November 17, 2017, http://marsadomran.info/en/policy_analysis/2017/11/1218/

[11] Yahia Shawkat, “EIPR Housing Policies Paper I: Analysis of the New Conditions for the Social Housing Programme” (Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, April 2014), https://eipr.org/en/publications/eipr-housing-policies-paper-ii-drafting-fair-housing-policy-egypt

[12] David Sims and Hazem Abdelfattah, “Egypt Housing Profile” (Nairobi: UN-Habitat, 2016), https://unhabitat.org/books/egypt-housing-profile/ p67

[13] See Table 3 for more detail on delivered SHP units

[14] The data set for total subsidized GSF units has been used which includes 25% non-SHP units, as there is no disaggregate for subsidized SHP units at the governorate level.

[15] NUCA, “Fath bab al-tahwil li hagezi al-i’lan al-thamin lil-mudun al-gadida al-tab’a li muhafazatuhum,” NUCA, December 28, 2016, http://www.newcities.gov.eg/dispNews.aspx?ID=2867

[16] GSF/SHF, “Report on the Activities of the GSF and the SHF Until 30/6/2017.”p8 and: Masrawy, “Bil-Tafasil: Al-Iskan Tatrah 6500 Wihda Bil-Si’r Al-Hur Dun Shurut,” Masrawy, November 12, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/y9v8rvj6

[17] At least 3000 units have been sold to South Sinai, and 588 in Ras Gharib to the Red Sea to use as compensation for victims of a flash flood. See: NUCA, “Wazir Al-Iskan Wa Muhafiz Ganub Sina’ Yuwaqi’an Protocolan Li Bei’ 3 Alaf Wehdah Sakaniyya Bil-Iskan Al-Igtimae’y Lil-Muhafaza Li Tawzi’iha ’ala Muwatiniha,” NUCA, March 18, 2017, http://www.newcities.gov.eg/dis_N.aspx?ID=204 and: Al-Masry al-Youm, “588 wihda sakaniya lil-mutadaririn min al-seyul bi Ras Gharib,” Al-Masry al-Youm, November 1, 2016, http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1033845

[18] Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Development. Kurasit Shurut Musabaqit I’dad al-Namazig a-Mi’mariyya wal-Tasmim al-‘umrani li mawaqi’ al-Iskan Dimn Birnamig al-Dawla lil-Iskan al-Igtimaey. June 2011.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Bonah, “al-Mashrua’ al-Faez bil-Musabaqa al-Qawmiyya lil-Iskan,” 09.08.2011, Bonah, accessed May 18, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/y9xb7s57

[21] While the MoH has a programme titled Social Housing Plots (aradi al-iskan al-igtima’ey), their pricing and sizes are targeted at middle-income earners, and the plots are concentrated exclusively in New Cities. There are also some projects for rural ad desert housing, though they are relocation projects and with very limited numbers compared to the SHP.

[22] Sada al-Balad, “Ta’akhur Istilam Wehdat Al-Iskan Al-Igtimae’y Yuthir Ghadab Al-Hagizin,” May 1, 2017, http://www.elbalad.news/2742511

[23] Al-Ahram, “Mai Abdelhamid Li Bawabat Al-Ahram: 10 Milyarat Shariha Thaniya Li Mubadrat Al-Markazy,” Al-Ahram, November 23, 2017, http://gate.ahram.org.eg/News/1645707.aspx

[24] Al-Wafd, “35 Alf Muqatin Sagalu Bayanatihim Khata’ Fil-i’lan Al-Tase’ Lil-Iskan Al-Igtima’ey,” Al-Wafd, April 25, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/y7dx8yoe

[25] Mai Abdelhamid, GSF Chairwoman and Director of the SHF. Personal interview, 13.12.2015

[26] Shukrallah and Shawkat, “Analysis: Government Policy Commodifies Housing.”

[27] Mai Abdelhamid, GSF Chairwoman and Director of the SHF. Personal interview, 13.12.2015

[28] Ann Blyberg and Helena Hofbauer, “Article 2 & Governments’ Budgets” (International Budget Partnership, February 2014), https://www.internationalbudget.org/publications/escrarticle2/

[29] It is projected to be 18% for FY 17/18. See: MoF, “Financial Statement of the State’s General Budget for FY 2018/2019” (Cairo: MoF, 2018). p95

[30] Calculated as total ‘Actual’ spending, mostly by NUCA, minus all other sources (income, loans, and grants).

[31] A conservative estimate based only on revenue from subsidised units sold to applicants according to SHF/GSF deliveries on each FY based on average unit prices and deferred to the next FY to allow for collection. No public information is available on other income for the SHF, such as donations, cash advances and land-sale allocations (25% of local municipality land and 1% of state land as per Social Housing Laws 33/2014 and 20/2015).

[32] A UAE grant was made to Egypt to build 50,000 SHP units. See: UAE Foreign Aid Reports 2013 through 2016 under ‘Infrastructure Development’ or ‘Urban Development’ https://www.mofa.gov.ae/EN/TheMinistry/UAEForeignPolicy/Pages/UAEFAR.aspx . AED figures exchanged to EGP based on contemporary exchange rates.

[33] An EGP 20bn loan was agreed for the SHF/GSF from four commercial state-owned banks in May 2016. However, only half the amount was disbursed by December 2017. See: Al-Mal, “Al-Iskan al-Igtima’ey yahsul ’ala adkham tamwil masrafi bi 20 milyar geneih,” Al-Mal, May 26, 2016, https://tinyurl.com/y8j9gown and NUCA, “NUCA Board Decision 112/11.12.2017,” NUCA, December 11, 2017, http://www.newcities.gov.eg/about/Decisions/dispdec.aspx?ID=325

[34] With the assumption that the balance of EGP 509mn in subsidies would be disbursed at the FY17/18 average of EGP 16,570 per unit.

[35] World Bank, “Projects : Inclusive Housing Finance Program (Financials),” World Bank Website, 2015, http://projects.worldbank.org/P150993?lang=en This follows on a previous $300mn loan for a similar, though simpler project enacted in 2009. See: World Bank, “Projects : Affordable Mortgage Finance DPL,” World Bank Website, 2009, http://projects.worldbank.org/P112346/affordable-mortgage-finance-dpl?lang=en

[36]The SHF/GSF and the World Bank have worked to eliminate “inefficient and poorly targeted supply-side subsidies,” instead supporting “transparent, well-targeted and economically efficient demand-side” subsidies that are paid to buyers upon purchase of a unit. See: World Bank, “Inclusive Housing Finance Program-for-Results Project – Project Appraisal Document.” p5 http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/319851468023373777/pdf/957910PAD0P15000100OUO090Box391428B.pdf

[37] MoF, “Financial Statement of the State’s General Budget for FY 2015/2016 (Enacted budget p73 & 81) and FY 2017/2018 (Actual budget under item “Low-income Housing Subsidy” p76).” https://tinyurl.com/7arzsv5

[38] MoF, “Financial Statement of the State’s General Budget for FY 2016/2017 (enacted budget p72 & 84), and FY 2018/2019 (Actual budget p82).” https://tinyurl.com/7arzsv5

[39] MoF, “Financial Statement of the State’s General Budget for FY 2018/2019.” p82 & 93 https://tinyurl.com/7arzsv5

[40] NUCA, “NUCA Board Decision 112/11.12.2017.”

[41] Al-Mal, “Al-Hukuma Tanfi Raf’a Al-Da’m ’an Al-Iskan Al-Igtimaey,” Al-Mal, April 19, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/y6u7uvz9

[42]10 Tooba, “BEDI – Overall Index,” Built Environment Deprivation Indicator (BEDI), September 2016, http://10tooba.org/bedi/en/

[43] CAPMAS, “Final Results of the General Census for Population, Housing, and Establishments for 2017 (Arabic)” (Cairo: Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS), December 2017), http://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/ShowPDF.aspx?page_id=/Admin/Pages%20Files/201710914947book.pdf

[44] David Sims and Hazem Abdelfattah, “Egypt Housing Strategy,” Final Draft (Cairo: MoH & UNHABITAT, May 2018).