- Published on 21 May 2025

In this study, a set of proposals is presented to reform the Old Rent (rent control law), in the wake of the ruling on the unconstitutionality of fixing rent values,[1] and as a response to the draft law proposed by the government,[2] as well as the ensuing discussions in the House of Representatives by MPs, tenants’ representatives, and landlords’ representatives. These proposals aim to safeguard the rights to housing and to private property, in a method that avoids social and economic crises, through four main pillars: Fair treatment of existing contracts, rent increases based on legal rather than market values, cash support for the most vulnerable tenants, and reform of the rental system as a whole, of both Old Rent and New Rent. The proposals are part of our Old Rent series, and were prepared in partnership with five human rights and research organisations and lawyers concerned with the right to housing.[3]

Also available to download

Contents

Pillar 1- Fair treatment of existing contracts

Pillar 3: Rent subsidies for low and middle-income tenants

Pillar 4: Full rental reform (Old and New Rent)

Pillar 1- Fair treatment of existing contracts

Some legal opinions have been voices that the Constitutional Court’s judgement does not address the duration of the contracts – which is for the lifetime of the original tenant and one generation of heirs according to a 2002 Constitutional Court judgement,[4] but only the fixing of the rental values. Other legal opinions and the government’s opinion favour the legality of curbing the duration of contracts, specifically termination after transitional period – of five years in the government’s draft.[5]

Problem with status quo:

– The duration of the lease is unknown (tied to the life of the tenant and one of his heirs), without possibility for the owner to break it for personal reasons (personal need for the unit), which creates a situation of inequality between owners due to unequal durations, in addition to economic instability due to not knowing when the unit will be recovered.

– The majority of owners demand that the units be vacated as soon as possible.

Problem with terminating all contracts at the same time:

– Creating a new economic and housing crises and a major imbalance in the real estate market when hundreds of thousands of tenants, half of them in Greater Cairo, are forced to look for alternative housing, whether for rent or ownership at the same time, which means risking monopolistic practices to significantly increase demand over supply by price gauging (as happened recently with the waves of refugees), with the risk that many tenants will not find alternative housing and will be displaced. This is in addition to landlords offering thousands of vacated apartments on the market, whether for sale or New Rent (market rent), within a short timeframe, flooding the numbers of units and lowering their prices, which may lead to them remaining empty for a long time and depriving the market of them.

– Asymmetry between landlords in the rental periods of the units, as the units were rented out for different periods.

– A large percentage of tenants have paid khilew rigl (key money), and/or paid for the finishing of unfinished units at the date of their rental, in addition to paying for the non-periodic maintenance of the property such as repairing or installing water or electricity infrastructure or renovation (usually the responsibility of the landlord), in agreements with landlords as compensation against the lower fixed rents, thus creating a tenure entitlement that differs from regular rental tenure and becomes a long-term usufructuary right.

Proposal to deal with the duration of the lease: All contracts will continue for the statutory periods with the ability for landlords to redeem the units before these periods in certain cases:

- Allowing individual owners to request one unit for personal use for themselves or one of their first-degree relatives (provided they have reached the age of consent), if the family (husband, wife, minor children or first-degree relatives for whom the unit is to be requested) does not own another residential unit that is not rented out under Old Rent. This would be against cash compensation of the tenant at 10% of the value of the unit (based on real estate tax estimates and not market value), and where the unit would be vacated after a transitional period equal to one month for every 12 months (year) that the tenant has lived in the unit.

| Length of tenancy | Time to vacate unit after own-use request |

| 30 years | 30 months (2.5 years) |

| 40 years | 40 months (3.3 years) |

| 50 years | 50 months (4.2 years) |

| 60 years | 60 months (5 years) |

| 70 years | 70 months (5.8 years) |

| 80 years | 80 months (6.7 years) |

- The tenant has rented more than one Old Rent unit. The non-permanently used unit is to be vacated within 6 months of reporting.

- The tenant (or the spouse or minor children) owns another residential unit, or an agricultural land plot (within the agricultural zimam) that exceeds one feddan, or an urban land plot that exceeds 100 sq. m. The unit is to be vacated within 12 months of reporting.

- If the unit is closed or not used permanently (used for less than 9 months per year) for three years or more. The unit is to be vacated within 6 months of reporting.

- If the unit is sublet, the Old Rent contract shall be terminated within 6 months of the approval of the law. The unit is to be vacated within 6 months of reporting.

- For units whose use has been changed from residential to another activity, these cases can be regulated by the proposals for dealing with non-residential units.

Pillar 2: Raising rental values as well as annual rent increases with a legal rather than market-based calculation

Problem with market-based values:

Rental prices have risen at much higher rates than income for the majority of the population, where rents devoured about 39% of the income of renting families in 2017.[6] Given the economic crisis and high inflation of the past three years, as well the exploitation by many landlords and brokers of the recent refugee crisis in Egypt,[7] and the unprecedented rise in real estate prices, rent to income ratios today will be higher than that.

Proposal: Establishing an official rent price index

- There is a need for an official rent price index as estimated by the real Estate Tax Authority, determined at the level of each neighbourhood. As the index will in all probability lead to rent values much higher than those in the Old Rent contracts, these ‘legal’ increases to the level of the index should be applied gradually over five years, starting at 60% of the value stated in this index and increasing by 10% each year until it reaches 100% of the index at the end of five years.

| Rent Increase | Period |

| To 60% of the index | Year 1 |

| To 70% of the index | Year 2 |

| To 80% of the index | Year 3 |

| To 90% of the index | Year 4 |

| To 100% of the index | Year 5 |

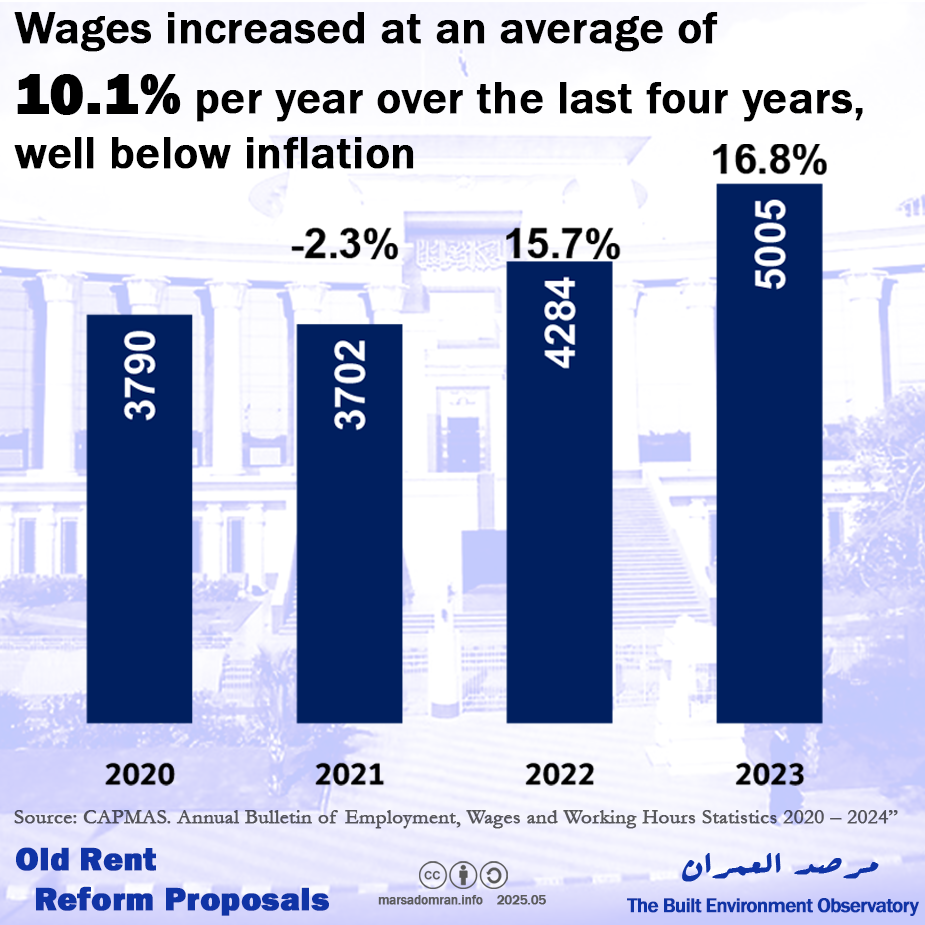

- After this period, the rent will increase on an annual basis determined by the government rent index based on the official rate of wage increases (according to CAPMAS data – Figure 1),[8] not the inflation rate.

Figure 1: Evolution of average monthly wage changes in Egypt over the last four years (LE/% change)

Pillar 3 :Rent subsidies for low and middle-income tenants

Problem: New legal rents may be unaffordable for many

While raising rents according to a legal rent price index rather than market values may curb the raises, the new rents will in all probability still be unaffordable for many tenants, given their low incomes, especially pensioners. In addition, the solution proposed by the government in its draft law to provide social housing units and other government units is based solely on liberalising the rental relationship and evicting residents. It is also unrealistic that the ministry can be able to provide housing units to all tenants that will find market housing unaffordable. According to recent statements by the CEO of the Social Housing Fund, the fund delivered 639,000 low-income housing units in ten years (between 2014 and 2024),[9] which is an annual average of 64,000 units per year. However, the number of tenant households in need of support is estimated to be at least 528,000 if we assume that the poverty rate of 29.7 per cent according to the latest income survey,[10] applies to the 1.6 million tenant households.[11] Therefore, it is difficult for the fund to build and allocate a sufficient number of units for these numbers of tenants in a short period of time, especially since there are new applicants for the previous announcements for the Housing for all Egyptians, and the upcoming seventh announcement, who have priority in receiving the units.

Proposal: Rental cash subsidies

The government should support low- and middle-income tenants in paying the new raised rents and staying in their rented units, with special criteria for the elderly and pensioners. The Ministry of Housing’s Social Housing and Mortgage Finance Fund (SHMFF) can establish a rent subsidy programme for low- and middle-income tenants, with priority for Old Rent tenants with the following provisions:

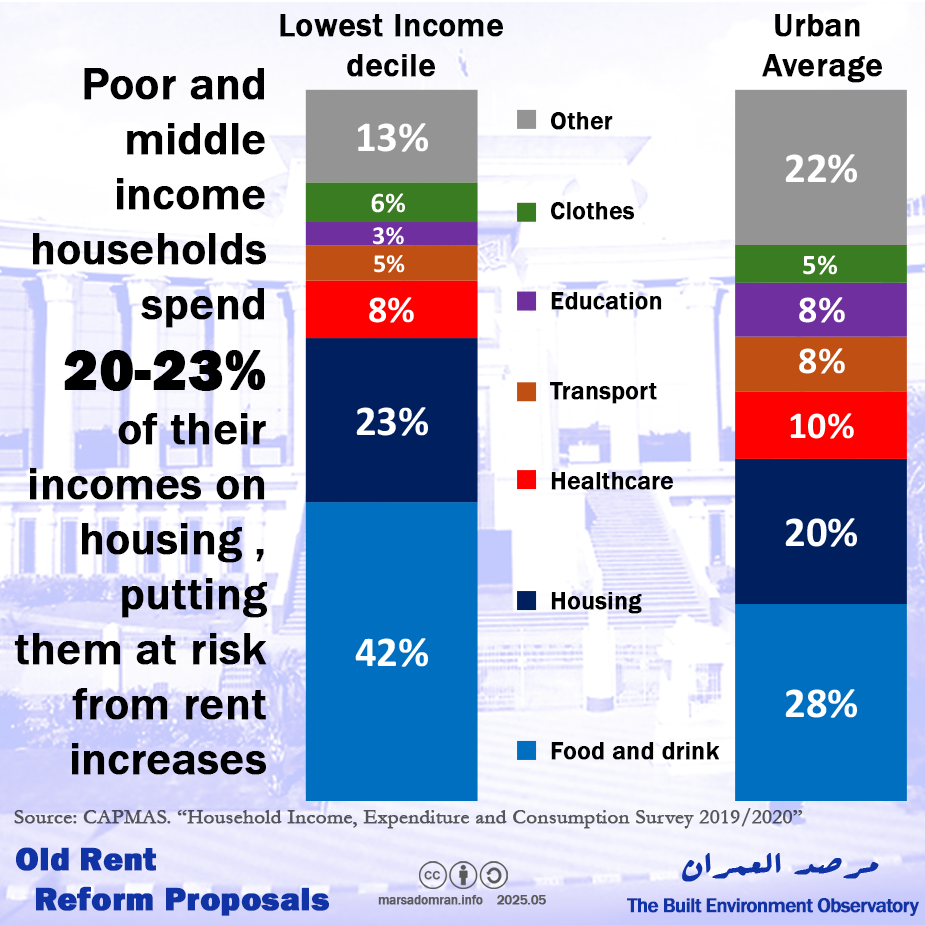

- Set an official rent-to-income ratio not exceeding a maximum of 20% (according to official statistics from the Household Income, Expenditure and Consumption Survey – Figure 2), where the programme will subsidise the difference between this limit and the legal rent that will be charged on the units by the official index.

Figure 2: Comparison of expenditure on basic needs between the poorest decile and average households (%)

- Subsidies should be provided for an open-ended period while re-examining eligibility every five years.

- Income conditions apply according to the latest SHMFF conditions for social housing (Housing for All Egyptians)[12] as follows:

| Income Bracket | Sub-bracket | Lower Income Limit (LE/month) | Upper Income Limit (LE/month) |

| Low Income | Individual (Single,widow,divorcee) | None | 12,000 |

| Family | None | 15,000 | |

| Middle Income | Individual (Single,widow,divorcee) | 12,001 | 20,000 |

| Family | 15,001 | 25,000 |

- The SHMFF should liaise with government agencies that are also Old Rent landlords, especially municipal governments that own old social housing (most pre-1977 housing was rented out, and later qualified for a right to buy scheme though many may still be rented), as well as the Awqaf Authority (religious endowments), if they could continue to subsidise rents, or offer rent-to-own schemes.

Pillar 4: Full rental reform (Old and New Rent)

Problem: Civil Code untouched since 1948, and market rents are unregulated

There is an urgent need to reform New Rent that is the Civil Code articles on rent, which have not seen any amendment or development since it was passed in 1948. This mainstream rental law will receive a large influx of Old Rent tenants when their units are liberalised, in addition to regulating over 1.4 million existing tenancies, though ones that experience runaway prices and eroding tenure security.

Proposal: Regulation and incentivisation

- Introduce price regulation by mainstreaming government’s official rent index (proposed for OId Rent) to be applied for all tenancies at the level of each neighbourhood and reviewed annually.

- Cap annual rent increases to the official rent index balancing between wage increases and inflation.

- Increase tenure security by stipulating minimum contract periods of 5 years, with the ability for the landlord to request the unit for personal use during the period in exchange for compensating the tenant for the unused period.

- Incentivise owners to rent out vacant units to exploit the large percentage of vacancies – estimated to be 12 million units according to official statistics, by exempting units rented to low- and middle-income tenants from real estate taxes, and establishing dispute resolution associations, to mediate between landlords and tenants as a first resort before seeking legal measures.

Acknowledgements

Written by: Yahia Shawkat and Nadine Abd El Razek

Input and discussion: Ahmed Awaad, Ibrahim Ezzeldin, Hossam Bahgat, Kholoud Saber, Mohamed Abdelazim, Mohamed El-Helw, Mohamed Lotfy, Moaaz Lafi.

Main image: Supreme Constitutional Court, Cairo – The Arab Contractors

Please cite as:

Yahia Shawkat and Nadine Abd El Razek. Reforming Egypt’s Old Rent law in light of the constitutional court ruling: Proposals to safeguard the right to housing. The Built Environment Observatory. 21 May 2025.

Notes and References

[1] Built Environment Observatory. “Egypt’s Constitutional Court Annuls Fixed Old Rents – Implications and Next Steps.” 24 March, 2025.

[2] Al-Youm Al-Sabea. “Old Rent.. We publish the complete draft law before its debate in parliament’s housing committee. (Arabic)” 4 May, 2025.

[3] Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, Diwan Al-Omran, Human and the City for Social Research, Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, Mohamed Abdelazim (Lawyer).

[4] Supreme Constitutional Court ruling on Appeal 40/18C. And: Al-Ahram. “Tenants refuse time limits to vacate unit.” (Arabic). 12 May, 2025. And: Al-Youm Al-Sabea. “Old Rent law… civil code expert: terminating tenancies contradicts constitutional ruling.” (Arabic). 6 May, 2025.

[5] Al-Youm Al-Sabea. “Is liberalizing tenancies part of the constitutional court ruling on Old Rent?”. (Arabic). 4 May, 2025.

[6] Built Environment Observatory. “Egypt Rent Statistics 1986 – 20217.” 8 February, 2018.

[7] Al-Shorouk. “Rent prices rose 60% in Egypt from the beginning of the year.” (Arabic). 7 May, 2025. And: Al-Manassa. “Rent chaos… Refugees are blamed but the fault is in the system.” (Arabic). 1 September, 2024.

[8] Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. “Annual Bulletin of Employment, Wages and Working Hours Statistics 2020 – 2024.”

[9] Cabinet. “Prime Minister follows up on funding and implementation of Housing for All Egyptians.” (Arabic). 17 March, 2025.

[10] Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. “Key Indicators of the Household Income, Expenditure and Consumption Survey 2019/2020.” p94.

[11] Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics. “Final Results of the General Population, Housing and Establishments Census for the year 2017.” Table 10. For a visual analysis of the Old Rent statistics, see: Built Environment Observatory. “Egypt’s Old Rent in 7 Statistics.” 27 November, 2024.

[12] SHMFF. “Housing for All Egyptians Ad 7.” (Arabic). 15 April, 2025.