- Published on 28 February 2022

A woman’s right to access safe and independent housing is an issue that cannot be seen isolated from the legal, socio-cultural, and economic barriers which hinder women from ownership of homes or land, and from control over their own ones. Considering the various layers of meaning housing holds for women, ownership, in this case, acts as more than an economic asset, yet as a spatial and social right as mentioned in the SDGs targets to “undertake reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property, financial services, inheritance, and natural resources, in accordance with national laws (Goal 5).”[1]

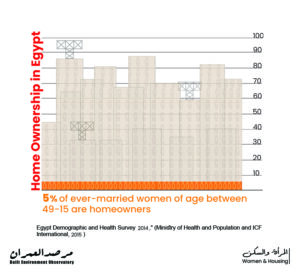

The lack of recent sex-disaggregated data specific to forms of housing and land tenure and control is a persistent issue to identify the actual current housing crisis of women. According to the limited available data, overall, only 5% of ever-married women of age between 15-49 are homeowners,[2] while the overall percentage of homeownership in Egypt is 77% according to the census.[3] The percentage of female landowners is equally low (4%), compared to male landowners according to government estimations in 2000,[4] while FAO statistics echo how only 5% of landowners were female in the same year.[5] The most recent statistics (from 6 years) indicated that only 6% of women of age between 18-64 have any forms of assets or properties, and eight out of 10 women do not have any independent income either from work or any other sources.[6] The barriers towards amelioration of the wide gender gap in land and properties statistics can be read through legal, socio-cultural, and economic aspects.

Legal barriers

According to Islamic law, the female offspring’s inheritance from her parents is only half that of a male offspring’s entitlement (0.5:1 ratio), while the wife’s inheritance from her husband is one eighth if she has children and one-quarter share if she does not. In the case of no direct male heirs, females have to share the inheritance with second or third-degree male relatives. Even these limited shares may not be transferred to female family members or are limited by conditional use and management by male family members.[7] In addition to this, the judiciary has been known to rule according to Islamic Sharia in cases of non-Muslim inheritance.[8]

For women who rent, the commonly named New Rent Law (Civil code articles), only rental details are stipulated, mostly according to the landlord, which does not define any legal rights to the tenant except for details like the rental period and monthly rent amount. This absence of legal protection mechanisms subjects women to different manifestations of gender discrimination in housing. In a recent study, women reported that they face landlords’ refusal to rent to them for being single, divorcees, or widowers, ‘it might have a bad influence on the building reputation’ they were told.[9]

This legal protection in housing is absent also when separation or divorce. Although women can adjudicate to the family court to secure housing payment from the ex-husband. Yet, the process is complex, costly, and time-consuming. The fact that the housing protection is not instant subjects divorced women with children to forced eviction and consequences of resettlement and loss of tenure rights if the rent contract is signed by her ex-husband, and especially if he stops paying the rent and the value could not be met by the woman

Even though Egypt is a state party to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which defines the lack of provision for the equal distribution of marital property as one of the discriminatory grounds at one hand, and considers joint or co-ownership of properties between both spouses from the important measures that the state shall take to eliminate discrimination against women at the other hand, practical implementations are still limited and gaining access through partners’ ownership is still a reality.

Socio-Cultural Barriers

As mentioned, ownership does not mean control, and the available data on housing ownership does not distinguish between that and does not offer any knowledge about how women’s control over houses may be subjected to changes, upgrades, or downgrades according to their societal and marital status. Customary practices limit women’s management of family assets of houses or lands that are generationally managed by male family members: husbands, fathers, brothers, or cousins.

The housing status of women is also significantly affected by domestic violence. It is estimated that one million married women leave their marital homes yearly due to domestic violence perpetrated by their spouse, and approximately 7.9 million women suffer different forms of family violence every year.[10] This prevailing violence subjects women to living under inadequate and insecure housing conditions or to bear manifold burdens of property replacement. Even bearing cost burdens and fleeing domestic violence and abuse leave women to other social barriers of landlords’ restrictions, and limited opportunities to find an appropriate rental unit due to the previously mentioned discrimination of landlords to rent their apartments to families. The ramifications of domestic violence and landlords/doormen’s guardianship leave women in a state of imminent homelessness without access to safe and adequate housing options.

Economic Barriers

From the start, women in Egypt have far less access to employment, and when they do work, a significant pay gap awaits them, which drastically limits the housing they can afford as independent individuals compared to men. This existing disadvantage puts them in a whirlpool of disadvantages that is almost impossible to escape, as living in poor and inadequate housing conditions may affect their capacity to generate income.

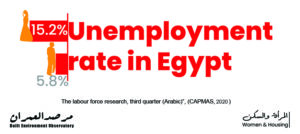

In Egypt, women’s unemployment rate is 15.2% compared to 5.8% for males.[11] Their participation in the labour force is 24.7%, where 20% of them work on a part-time contract.[12] Women’s tendencies to work in part-time jobs, short-distance jobs, or home-based/neighborhood-based work make them the most vulnerable family member to inadequate housing conditions, especially considering the fact that 7.7% of households are living in extremely crowded housing conditions, 17% of them are deprived of access to safe water, while five out of 10 families experience the lack of improved sanitation, and 3.2% are housed in precarious or non-durable buildings.[13]

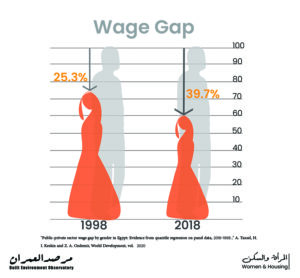

As for the pay gap, the minority of women that do work is estimated to earn between 25 to 40 percent less than males with the same education and experience level, a wage gap that keeps escalating from 25.3% in 1998 to 39.7% in 2018.[14] Generally, the estimations indicate that men’s average income is about 3.8 times women’s,[15] which clearly results in a housing affordability gap.

Ultimately, while most of these legal, socio-cultural, and economic barriers are deep-rooted, addressing them with consideration to their permeation through women’s possible housing options is crucial. This ensures ending the process of women gaining access to the housing system through male family members.

Acknowledgments

Written by: Reem Cherif

Reviewed by: Yahia Shawkat

Main image: Nouran El Marsafy

Notes and References

[1] “Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” (United Nations General Assembly, 2015) Available: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html

[2] “Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2014,” (Ministry of Health and Population and ICF International, 2015)

[3] “Number of Egyptian Families and Individuals by Type of Home Ownership: Housing Conditions (Arabic),” (CAPMAS, 2017)

[4] “Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa – Egypt,” )Freedom House, 2005( Available: https://www.refworld.org/docid/47387b6a46.html

[5] “Gender and Land Rights Database,” (FAO, 2000) Available: http://www.fao.org/gender-landrights-database/data-map/statistics/en/

[6] “The Egypt Economic Cost of Gender-Based Violence Survey (ECGBVS) 2015,” (CAPMAS, United Nations Fund Population (UNFPA) and National Council for Women (NCW), 2016)

[7] El Khorazaty, Noha. Egyptian Women’s Agriculture Contribution; Assessment of the Gender Gap for Sustainable Development. 2021. American University in Cairo, Master’s Thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1533

[8] “Christians in ID … Muslims in inheritance” A new campaign from EIPR calling for Christian women’s rights in applying the principles of their law in inheritance shares distribution,” (The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR), 2019) Available: https://eipr.org/en/press/2019/07/christians-id-muslims-inheritance-new-campaign-eipr-calling-christian-women%E2%80%99s-rights

[9] “Homes or Just Houses: The Housing Needs of Female-Headed Households in Egypt,” R. Hamad, A. S. Abd Elrahman and A. Ismail, Journal of Building Construction and Planning Research, vol. 6, pp. 138-150, 2018.

[10] “The Egypt Economic Cost of Gender-Based Violence Survey (ECGBVS) 2015,” (CAPMAS, United Nations Fund Population (UNFPA) and National Council for Women (NCW), 2016)

[11] “The labour force research, third quarter (Arabic)”, (CAPMAS, 2020)

[12] “The impact of the fourth industrial revolution on women in the information and communication technology sector: an in-depth analysis on the future of labour (Arabic),” (Baseera, the World Bank, National Council for Women, 2021) Available at https://www.enow.gov.eg/Report/133.pdf

[13] “Overall Indicator of Deprivation in the Built Environment,” (The Built Environment Observatory, 2016) [Online]. Available: https://10tooba.org/bedi/en/homepage/

[14] “Public-private sector wage gap by gender in Egypt: Evidence from quantile regression on panel data, 1998–2018,” A. Tansel, H. I. Keskin and Z. A. Ozdemir, World Development, vol. 135, 2020

[15] “The impact of the fourth industrial revolution on women in the information and communication technology sector: an in-depth analysis on the future of labour (Arabic),” (Baseera, the World Bank, National Council for Women, 2021) Available at https://www.enow.gov.eg/Report/133.pdf