- Published on 30 January 2018

As part of the BEO’s 2017 | State of Rent series, we take a look at in-kind housing, a from of tenure linked to one’s employer where rent is deducted from the salary, hence known as tied accommodation. Based on the 2017 Census, over half a million people in Egypt were living in 130,706 in-kind units. To read other articles in the series, please click here.

Introduction

Large industrial complexes started to develop with the advent of steam power at the turn of the 19th century. Among the initial impacts those complexes had were the crowding of cities and the deterioration of living conditions within them, especially for the working class.[1] Those deteriorating conditions started to affect production capacity through ensuing epidemics and other health and environmental threats that affected workers lives and hence interrupted production capacity, and the lessons brought forth by Engels in his book ‘The Living Conditions of the Working Class in England’ started to fall on more attentive ears.

Among the first to follow those lessons were the Lever Brothers, who established a settlement in the late 19th century for their factory workers in Merseyside in northern England and called it Port Sunlight. By 1911 it had 3500 inhabitants – employees and their families – living in 800 homes. The settlement had public facilities like churches and healthcare.[2]

Company Towns were introduced to Egypt in the later 1800s, when the Suez Canal Company planned, built and largely managed the towns of Port Said, Ismailia and Suez. Oil companies followed suit in the early 20th century, and the Anglo-Egyptian Oilfields Company (AEOC) built a labour camp in the vicinity of Mt. Gharib in 1938 on the western coast of the Gulf of Suez, almost half way between Sokhna and Hurghada where their operations were located. The camp later evolved into the town of Ras Gharib.

1938 – 1962 Ras Gharib as a Company Town

The first site with proven petroleum capacity was further south along the coast in Gebel El Ziet – the Arabic translation of Oil Mountain, where travellers could observe crude oil bubbling from below the rocks. This attracted the attention of the Egyptian State as well as private – mostly international – investors to come to the region and start prospecting for petroleum. The Royal Dutch Shell Oil Company and the British Petroleum Company established a joint venture in order to start their business in Egypt, establishing the Anglo-Egyptian Oilfields Company (AEOC) in London in 1909 and started operating in Egypt at 1911. They first worked in Gebel El Ziet, then in Hurghada before moving to Ras Gharib in 1938. By the next public census in 1947 the town had 3799 residents.[3]

AEOC was responsible for providing their staff with almost all they needed for their lives. The upper management of the company stayed in houses with stone foundations which were slightly elevated from the surrounding ground, walls made of a mixture of masonry and wood, with tiled roofs. These houses were located on the seafront, with plenty of space between units, allowing for more privacy. The workers on the other hand were stationed in brick houses with wooden roofs that were built in rows looking slightly like trains, and hence nicknamed by the local population as ‘Masaken Al-Qutorat’ – Train Houses. Those were significantly denser and located closer to the company’s main site at the northern part of the town.

AEOC kept their refining operations away from Ras Gharib, in Suez closer to the main markets in Cairo. That limited the economic development potential in Ras Gharib to petroleum extraction.

1962 – 1991 Hybridisation of Company & Municipality

Ras Gharib Municipality was established in 1962,[4] and in 1964 AEOC was nationalised and their operations were transferred to the General Authority for Petroleum Affairs (GAPA)[5] and split between two subsidiaries; Al-Nasr Petroleum Company, which took over the refining facilities,[6] and the General Petroleum Company (GPC), which took over the extraction facilities around Ras Gharib.[7] GPC remained the main employer despite the opening up of the market for other private petroleum companies, and continued to be the main services provider in Ras Gharib; allowing all residents – even non-GPC employees – to commute using GPC vehicles free of charge, providing of meals for school children, healthcare for employees, and recreational facilities to the public, some in collaboration with the local municipality.[8]

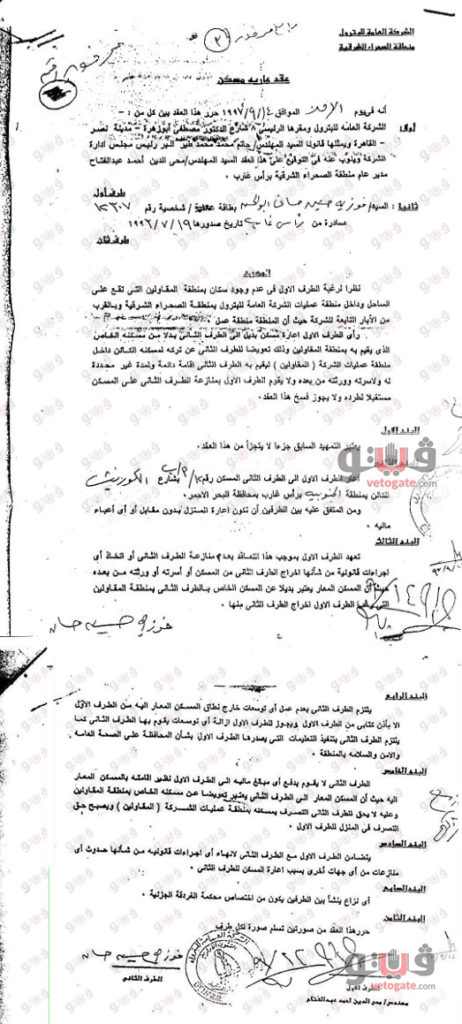

GPC continued to offer housing for their staff resulting in most of the urban expansion of the town. The tenancy agreement that governed the relationship between the company and its workers was a so-called Lending Contract (Figure 1). It is a form of tenancy that allows the tenant to use a unit free of charge, for a fixed term – in this case employment – without transferring ownership. As with rental, the tenant cannot affect any permanent change to the unit without prior permission from the owner, and is obliged to return the unit to its original situation by the end of the term. In rare cases, the company-built houses for its employees who would then buy them through a long-term lease-to-own agreement, paying it off through instalments deducted from their salaries.

Figure 1: Lending Contract made out by GPC to one of its employees in 1997. From: Veto Gate 2017

1991 – Present: GPC rolling back, Government stepping in

In 1983, the GAPA became the General Petroleum Authority (GPA), changing from a public agency to a state-owned holding company, with subsidiaries – like the GPC.[9] That would set the stage for the neoliberal changes due to happen in the following decade. GPC continued to be the main service provider in Ras Gharib, expanding with its population until the early 1990s, becoming very intertwined in the lives of its people. But in 1991, law 203/1991[10] was passed as part of the structural adjustment policies imposed by the World Bank, paving the way for neoliberal changes that would reshape the Egyptian public sector.

The first step was shedding off all the possible costs that ‘burdened’ the public sector; namely services provided to workers. As employees began to feel the impact of this retreat, the GPC Workers Union pressed the company administration to sell them the units occupied by them. That demand was positively received at GPC as it meant that the cost of maintenance and utilities of the aging buildings, which in 1997 was EGP 7.7 million,[11] would also be transferred to the workers. At the same time, instead of having permanently residing staff, GPC was preparing a new shift-based labour camp in nearby Ras Bakr, signalling an end to the employment of permanent workers.

However, the legalities of selling the homes were complex, as the company did not own the land the buildings occupied, but was awarded a concession for a set term to use it for oil extraction.[12] Once the term ended, it was up to the government to obligate GPC to remove these buildings or transfer ownership to the government.

Thus, GPC proposed to hand over the housing blocks to the Red Sea Governorate, whom would in turn sell them to the tenants. This meant that GPC could not sell those homes directly to the tenants, and both parties needed the government to act as an intermediary to finish the deal. The 936 units had a total book value of 3.3 million EGP in 1998, which after depreciation would be EGP 961,000.[13] This of course is just an accounting value, used to transfer assets from GPC to the Red Sea governorate, and not the actual price the units will be sold for to the employees.

This transaction though, left out the 105 units of stand-alone executives’ houses on the seafront. Over half (69 units) were assigned to their GPC occupants by means of hereditary ‘lending’ contracts which are a life-long lease that can be passed on to the tenants’ heirs. The tenants of those units varied between – then – GPC employees, retirees, and heirs of former employees. This means that tenants can stay in those houses for as long as they want, and as long as the houses are standing, but they cannot sell them, or, buy them (Figure 1). The rest of the seafront houses have a number of uses. 15 are used as guesthouses for visiting company personnel, 13 lodge visiting contractors, and six are in use by government agencies including the Mayor, Army Intelligence Department, the Police Inspector, Police Prefect, and Traffic Inspector. A further two houses were lent to an individual and an NGO for their services to the local community.[14]

But the GPC employees, retirees, or their heirs who have the lending contracts, were recently given eviction orders by GPC, even though the lending contracts clearly state that they cannot be broken (Figure 1), while the tenants were also able to acquire GPC approval in 2012 to buy the units they occupy.[15] Twenty of them went on hunger strike last month to protest the orders,[16] amid rumours that GPC, along with the Red Sea governorate wish to capitalize on this lucrative seafront location, as part of a new national asset management policy.[17]

A Future for Company Towns?

The situation in Ras Gharib as a company town home to around 60,000 people,[18] is quite different from workers’ compounds, or mosta’marat (colonies) as they are called in Egypt, which house hundreds of people. While a local government municipality exists, there are no clear boundaries between its roles and those of the company. But since 1991, with the transformation of the public sector into holding companies and the start of a trend of shedding off fiscal burdens from those newly converted holding companies, service provision in Ras Gharib began to be increasingly moderated by the local government.

The town’s strategic plan issued in 2000 designated the area west of the existing urban mass for future development, and the plots were to be allocated by the local government. It was the first effort for organised non-GPC moderated housing development in the town. Currently the government is actively pursuing the removal of the self-built community next to the GPC northern camp and relocate the residents into another location currently under construction in the south-western end of the town. That area is also seeing a lot of construction activity as a new hospital is being constructed with a number of other service facilities being moved there.[19]

The local government is also taking on more responsibility from GPC in service provision, the success of which is conditional to the diversification of the local economy. But the transfer to municipal rule is far from over. In the last episode of extreme rain events in October 2016, where a large part of Ras Gharib was flooded, it was the tools and machinery of GPC and later of the Army Corps of Engineers that did most of the debris removal and rescue efforts.[20] While the absence of non-GPC jobs for the town’s residents and the flight of foreign investment from the national petroleum sector in general and the town specifically, has meant that more residents are inclined to leave the town in search for better opportunities, while those working in the petroleum sector are more willing to make more concessions in return for remaining with an increasingly corporate, and less welfare GPC.

Acknowledgements

Written by Ali Almoghazy, and revised by Yahia Shawkat

Main image: Ras Gharib, October 2015, OrderinChaos Creative Commons Licence 4.0

Notes and References

[1] Engels, F. (1845) The Great Towns: from the Condition of the Working Class in England 1844. Excerpt from the City Reader 5th Edition.

[2] Miller, M. (2010) English Garden Cities: An Introduction”. English Heritage.

[3] Hamdan, G. (1959) Studies in Egyptian Urbanism. Cairo. (Arabic)

[4] Ministerial Decree No. 603/1962 by the Minister of Local Administration of the United Arab Republic Establishing the City Council for Ras Gharib.

[5] A.A.P. – Reuters (1964, March 26th), Nasser Seizes Oilfields, The Canberra Times. Retrieved from https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/104276228

[6] Historical Brief on Nasr Oil Company. Official website of Nasr Oil Company. Retrieved from https://www.nasroil.com/1.htm.

[7] History. Official Website of the General Petroleum Company. Retrieved from http://www.gpc.com.eg/index.php/about-gpc/history/

[8] Almoghazy, A. (2016) Masters Thesis Site Visit Report: Ras Gharib, February 17th, 2016.

[9] Presidential Decree 433/1983 for the Supervision of the General Petroleum Authority over the petroleum industry’s Public-Sector Companies

[10] Public Sector Companies Law 203/1991

[11] Mozakkera lra’ees magles edara al sherka al’aama lelbetrol lel’ard ‘ala algam’ea al’omomeya lel shareka. Memorandum by CEO of the General Petroleum Company to be shared with the General Assembly of the Company, documents numbered 1/79 and 2/79, n.d., in: “30 Osra bi Ras Gharib Mohaddada bil-Tasharud bi Sabab Villal al-Kibar”, Veto Gate. 21.04.2017. Retrieved 28.07.2017 http://www.vetogate.com/2675334

[12] Article 45 H, Minister of Industry, Petroleum and Mineral Wealth 758/1972

[13] Mozakkera lra’ees magles edara al sherka al’aama lelbetrol.

[14] ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] “‘Ummal Mutaqa’idun bi al-‘Amma lil-Bitrul Yudribun ‘an al-Ta’am.. wa Matalib bi Tadakhul al-Wazir”, Al-Masry al-Youm, 19.12.2017 http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/1233748

[17] A cabinet level Committee to Inventory Unused State Assets was established in 2015 to “build a database of unused assets… and establish a plan to utilise them in a manner that would realise the highest possible return” (Prime Ministerial Decree 2589/2015). Land and property belonging to GPC or the Red Sea governorate would fall within its jurisdiction, while it is not unprecedented that other state-owned entities have moved to evict tenants of company housing for the purpose of real estate investment. See for eg. Shawkat, Y. (2016s) Property Market Deregulation and Informal Tenure in Egypt: A Diabolical Threat to Millions. Architecture_MPS, Volume 9, Number 4, June 2016, pp. 1-18(18) http://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/uclpress/amps/2016/00000009/00000004/art00001

[18] Ras Gharib – Red Sea Governorate website. N.D. Retrieved 10.01.2018 http://www.redsea.gov.eg/ras%20ghareb.aspx

[19] Almoghazy, A. (2016) Masters Thesis Site Visit Report: Ras Gharib, February 17th, 2016.

[20] Albedaiwy, M. (2016, October 29) Ra’ees alhay’a alhandaseya: aldaf’e bemo’eddat le7al azmat alseyol bera’s gharib wa alhager. Alyoum Alsabe’. Retrived: 12.12.2017 https://goo.gl/DcZhva